‘We are the lost tribe of Alice Springs’: The families living in third-world conditions just five-minute drive from town centre

Residents of Irrkerlantye live a short drive out of Alice Springs and have been fighting for basic amenities for 40 years. They have one wish for their children: To walk tall in “both worlds”. Watch the video.

Northern Territory

Don't miss out on the headlines from Northern Territory. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Just a five-minute drive from the town centre of Alice Springs, lies the “forgotten” community of Irrkerlantye, where families either swelter in the desert heat, or freeze in their tin shed homes all year round.

In a country as prosperous as Australia, you would be naive to think that such places don’t exist, but for the 15 to 20 people who live there in “third-world” conditions, it is a reality.

Also known as White Gate, there is no electricity, no sewerage and no running water, except for a tank installed two years ago, and solar panels that supply meagre power “sometimes” throughout the week.

Felicity Hayes, a Traditional Owner of Mparntwe, the Arrernte name for Alice Springs, has been fighting to see basic amenities installed in her community for 40 years.

“I always say, we are the forgotten tribe of Mparntwe, the biggest town in Central Australia and we’re the ones that are the Traditional Owners for this country,” she says.

“We feel that we are lost … like we’re the lost tribe and we’re the Traditional Owners of Alice Springs and yet nobody comes around and asks us what we want you know.”

Despite achieving a positive Native Title determination in 1999, third-world living conditions have barely changed for her people, from living in “humpies”, to what she now calls an upgrade of humpies.

Out of the 17 town camps surrounding the town, hers is the only one without electricity and running water.

She says without properly built homes and other essentials, “uncertainty” surrounds the future of Irrkerlantye and the children who come from there.

Her goal for their future is for them to be educated in both Arrernte culture and western society, giving them the strength and confidence to walk tall in “both worlds”.

She says basic amenities in her community would go a long way to making that a reality.

“I’m concerned about their future because they need a good house, a good place to live in where they can learn and be safe and have a healthy living,” she says.

“Learn to live healthy and keep away from everything and what’s happening in town.

“I need my children to learn more language to get a good job, to go to school … to get an education.”

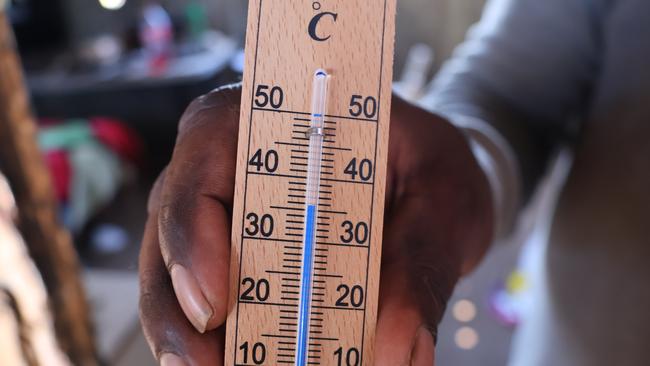

At 10.30am in the morning, temperatures can soar to 35 degrees or above in Irrkerlantye.

Sitting on his bed under a makeshift shelter constructed with poles, sheets and tree branches, Felicity’s nephew John Hayes explains the day-to-day of living there.

A quiet person, he is hesitant to speak about his situation, but Felicity encourages him to, in the hopes it will bring attention to their struggle.

“I live here with my little brothers … four of them,” he says.

“We got to walk to town … sometimes we got no power … there’s limited power out here.

“We need a house aye … brick house be good.”

“Water too … running water.”

“Everyday” people who live there make the 45 minute walk to the nearest bus stop to get a ride into town to get supplies, attend appointments or find somewhere to escape the heat.

They usually stay in town until it is cool enough to return, which isn’t until it starts to get dark.

“They have to go early in the morning at around about six or something you know just to get into town for appointments,” Felicity says.

“It’s really hard.”

Felicity says it is “no way to live”, which is why she is fighting to have tenure in her community in order to build infrastructure for the next generation.

She also works as an educator, taking children out on country and teaching them culture two to three times a week, with the aim of giving them a safer future.

It’s in stark contrast to what is taking place back in Alice Springs, where youth crime and violence has plagued the town for years.

The grassroots organisation where Felicity works, Children’s Ground, advocates for families to live with “dignity and justice, free from economic poverty”.

Co-founder Uncle William Tilmouth is a member of the Stolen Generation and has dedicated his life to helping Aboriginal families achieve equal opportunity in all facets of life.

He says the impacts of colonisation are still being felt today and says the only way forward is for the next generation to be strong in culture and western education.

“White Gate’s fighting for justice … justice to live on their land, to live with the same amenities everyone else takes for granted,” he says.

“Quite frankly they are forgotten about or ignored because of their title.

“They deserve just as much as anybody else … and they deserve to have their rights recognised and the injustice overcome.

“Ultimately, at the end of the day, Aboriginal people are pushed to the fringes of society … and they live on the fringes of the fringes now.”

In 1970, the Northern Territory Land Rights Act was introduced and it paved the way for Aboriginal people living on the fringes of the town to apply for tenure under special purpose leases.

If approved, Traditional Owners could secure essential services, infrastructure and housing, which ultimately progressed to the development of town camps.

Traditional Owners of Irrkerlantye applied but were denied tenure, and since gaining a positive native title determination in 1999, have been unable to successfully negotiate an Indigenous Land Use Agreement with the Northern Territory government.

In a statement to The Advertiser, the NT government said it has been negotiating an Indigenous Land Use Agreement for Irrkerlantye, but was waiting on all traditional owners to agree to the terms.

“The Northern Territory government is working with residents and native title holders of Irrkerlantye to support the negotiations regarding appropriate land tenure for the community,” it read.

“The granting of tenure will provide a pathway to resolve long-standing issues in Irrkerlantye.

A change in tenure requires the consent of native title holders and the Northern Territory Government is waiting on a decision of the native title holders.”

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘We are the lost tribe of Alice Springs’: The families living in third-world conditions just five-minute drive from town centre