The day after Jack died, Ken sat down in his son’s bedroom with tissues and whisky and started writing to him

What would Jack Fleming have made of the toast raised to him at his five-year high-school reunion in North Hobart last November?

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

What would Jack Fleming have made of the toast raised to him at his five-year high-school reunion in North Hobart last November? No one will ever know because when the head boy paid tribute to him, Jack had already left.

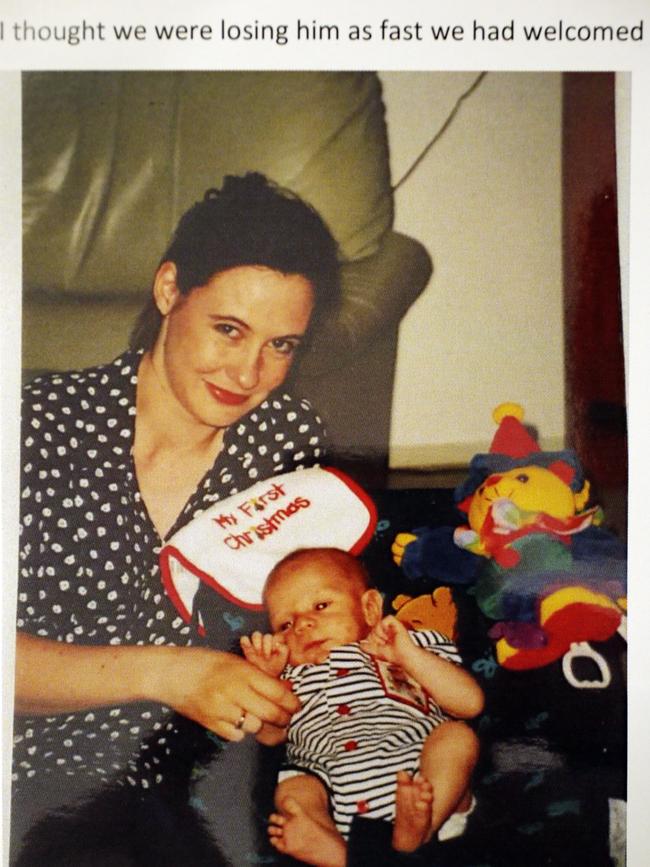

Jack Evan Fleming, born on November 25, 1996, died from a rare form of brain cancer in April, 2018.

His father Ken seems pleased to hear that his beloved third son’s absence was acknowledged by his former Friends’ schoolmates at the Year of 2014 get-together at Room For a Pony bar/cafe, but it is hard to know. Ken is still wiped out by grief.

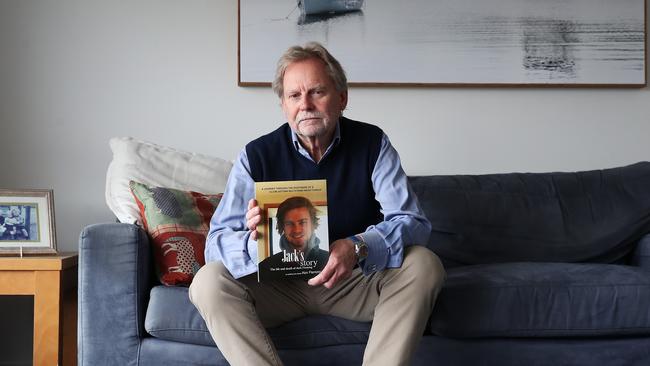

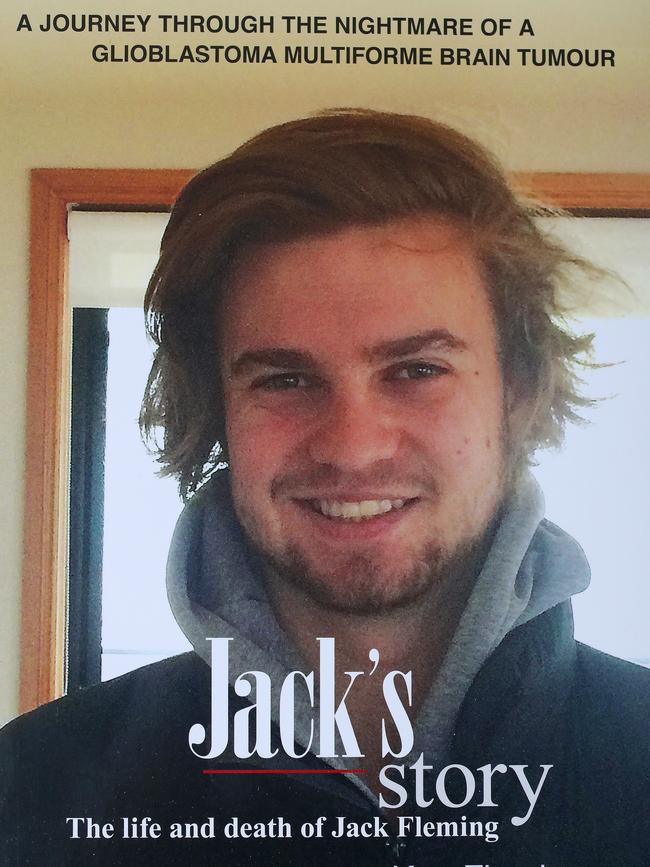

Though candid and astute when we meet, and keen to share plans for the development of a national centre for brain cancer in his son’s name, the quietly spoken former Sydney financier also seems vanquished and burnt out after a quixotic quest he was doomed to lose. Fatalistic expressions are now part of his lexicon. “Shit happens,” he writes in the introduction to Jack’s Story, his book about his son’s life and death, aged 21, following a diagnosis in July 2016 of glioblastoma multiforme brain cancer.

The day after Jack died, Ken sat down in his son’s bedroom with tissues and whisky and started writing to him.

“Jack was extremely bright but his cognitive abilities became compromised,” says Ken, explaining how he came to write the book. “He would tell me that the best thing was for him to keep working on the bottling line at Lark Distillery [which he joined after working at the Lark whisky bar in Hobart]: ‘I will never get to finish university, I’ll never become a professional person and I’ll never work overseas. And that’s OK.’

“And I’d say ‘no, I’m going to write a book about how I saved your life, then we are going to get $2 million, Jacky, and you’ll never have to work again’. It was our little game and that’s how the book came about. When he died I started writing to him in his room — tap, tap, tap — and suddenly I’m writing a book.”

Ken kept a diary through Jack’s treatment, which became the book. Jack’s Story: The Life and Death of Jack Fleming makes harrowing reading, but Ken is a strong storyteller. The pages are alive with joy as well as sorrow as he describes family life with six sons. After federal Health Minister Greg Hunt received a copy, he rang Ken to thank him and the pair has since met, with Mr Hunt endorsing Ken’s advocacy for new brain cancer treatments.

“There is something about paediatric and adolescent brain cancer that tears at the fabric of all of us, because parents see their children fade before their eyes,” Mr Hunt told the Sydney Morning Herald late last year. “Australia has the highest rate of brain cancer survival, but it’s still only 22 per cent, which means we need new treatments, immunotherapies and powerful advocates such as Ken.”

In Jack’s final months, the medical team advised Ken “just kiss him good night and spend the little time you’ve got left with him”.

“I didn’t resent that, but to me it was the wrong advice,” says Ken, describing his state of mind at the time as delusional. “In retrospect it possibly was the right advice, but we still thought we could [save him]. Did we buy time? We might have bought some time … we’ll never know.”

There is so much Ken, his mother Dianne and Jack’s five brothers will never know about the disease that took their son and brother. Doctors can’t tell them, they don’t know either.

Ken remembers hovering between despair, acceptance and hope, “accepting the fact that he was going to die but inwardly hoping there was a miracle due the family and he would pull through”.

“I recall so strongly that feeling that if he could finish university — somehow — and we — somehow could save him, life would go on almost as if this event never happened. And I said this over and over in my head and to anyone who would listen [voluntarily or reluctantly].”

Ken reached for help where he could. He says there was no limit to his manic capacity to research the disease and contact any person or institute he thought could help save his son’s life. He often told himself and others “I will not bury my son, not now, not ever”.

“Over the weeks and months that lament changed to ‘I will bury my son if I have to and we, as a family, will stand strong and united’. Oh such brave words, from someone who felt anything but brave.

“So much promise, so much life, so much intelligence. All to be eroded and destroyed by a disease that does not discriminate by age, race or gender. It takes no prisoners. It is like watching someone with Alzheimer’s — forgetful, struggling to comprehend words, let alone sentences. It reminded me of when Jack was 4 or 5. ‘[He’d ask things like] ‘what’s this word mean? What does this mean? Can you read that to me? Do I know that word? Pizza, pizza? I know what that is, what does it look like?’”

In his torment Ken sometimes imagined himself physically destroying the tumour.

“There were so many times, when no one was looking, I would grab the tumour in my hands and wrestle with it to the floor, stamp on it and choke it to death. I would eat it, crush it, smother it, destroy it.”

Ken describes the family’s journey as a slow march into hell, but he says Jack never gave up. “About two or three weeks before he died, I started to tell him that I thought maybe it was the end and, you know, we just need to say goodbye, but he got upset and agitated. Dianne just cut the conversation and said ‘what Dad means is possibly you can have a little bit of sugar today, but tomorrow we get back on the diet and we get strict again’. Then he was very satisfied. We had kept him on this keto-type diet because we thought it was making a difference. In the end, we realised it wasn’t but he felt it still was.”

Jack was an easy baby, a self-contained child and a quiet achiever who excelled at school, sport and chess. He did not like being the centre of attention. How to describe his essence in an anecdote?

“Probably the best example I can refer to is when he was in preschool at Lady Gowrie in Battery Point,” writes Ken. “His teachers adored him as he was such an easy child but he tended to play by himself. When we would pick him up in the afternoon, he would always be sitting in a corner, cross-legged with a puzzle and fully absorbed in what he was doing. As he sensed your presence he would look up and smile, “Oh it is time to go already?” as he stood and took your hand.”

When he was six, it was discovered that Jack was nearly deaf and thereafter he wore hearing aids.

“He became very shy and reserved and blamed those traits on his hearing loss and fear of speaking out of context because he missed the cue,” Ken says. “He also exploited it and referred to himself as the ‘disabled one’ and when Dianne was on his case he sometimes turned his hearing aids off and said loudly, ‘I can’t hear you.

“He used to joke as his brain became more addled from the cancer and treatments, and he lost a lot of his sight from one of the drugs we introduced — ABT414 — that he was becoming deaf, dumb and blind.”

As a teenager, the quiet boy seemed robustly healthy but he became even more enigmatic, at least to his father, Ken says.

“He didn’t bring friends home, although he was always out with friends. We often quizzed him about a girlfriend, but he would typically clam up, smile and walk away. The irony is that we really only started to know the mature Jack after he was diagnosed and became increasingly fragile and vulnerable.

“But there was always a quiet charm in the room when Jack was there and you couldn’t help but feel the strength of his personality, and his quiet but powerful presence. And he had the unequivocal respect and adulation of his younger brothers.”

In his last year at The Friends’ School Jack won an Australian Stock Market challenge for Tasmanian students and thought he might follow in Ken’s financier and company director footsteps, enrolling in Law and Business at the University of Tasmania. He flew through first year and made a strong start to first semester of second year.

On the evening of Friday, May 27, 2016, Jack played soccer at King George V oval at Glenorchy. It was a cold night and Ken, who tried to get to all his games, watched from the clubhouse, admiring his son’s speed and agility on the wing.

The next evening Jack complained of a headache and suffered a grand mal seizure. A scan showed a cloud suspected to be a tumour, but the family was assured it was not uncommon and most likely benign. Neurosurgeon Andrew Hunn undertook a biopsy. The bombshell came at an appointment with Dr Hunn on July 8. “I am afraid I have bad news for you, Jack, and wish there was some other way to tell you, but you have brain cancer and it’s terminal,” the neurosurgeon said.

Glioblastoma multiforme is one of the most common and aggressive brain cancers, killing more children than any other disease and more people under 40 than any other cancer. The survival rate today for children diagnosed with leukaemia is 87 per cent, but for GBM it is 5 per cent. The average lifespan after diagnosis is just over 12 months. And there have been no improvements in patient outcomes in 50 years or more.

Ken’s focus now is on helping to create a world-leading brain cancer research centre at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, where crucial forensic pathology testing of Jack’s tumour was done (with most of his treatment undertaken in Hobart).

Ken is working with doctors and medical researchers at RPA, NSW Health and the University of Sydney to establish a National Centre for Brain Tumour Neuropathology, which the hospital has asked for his permission to name The Jack Fleming Centre. Funding is being sought from the federal and NSW state governments to create a platform for translational research.

The proposed centre’s focus is on moving from a one-size-fits-all treatment for malignant brain tumours in adults to individualised treatments guided by neuropathology diagnoses and molecular testing. The premise is that a more comprehensive characterisation of tumours could better inform oncologists as they choose treatments including new drugs. Jack’s treatment changed dramatically after such testing, says Ken, allowing his medical team to try the new drug ABT414 following surgery.

Ken says he learnt quickly that because no one knew how to kill the disease before it killed the patient, there was latitude to trial different approaches.

Though some existing treatments may buy time, it is usually highly compromised time. Ken’s heartfelt wish is for the centre to be funded as soon as possible and working towards giving more time and a better quality of life to brain cancer sufferers.

When he recently met a man who had lost a daughter, Ken says he told him he cannot forgive himself for Jack’s death.

“As a father my job was to save his life and I didn’t do it. People can say science is against you, I get that. Jack knew I did everything I possibly could. My family knew that, too. But it doesn’t matter: I lost a son and my job is to look after my children. That guilt will go with me, but it may be appeased or diluted if I save another life through the Jack Fleming Centre …

“It’s all about science and money. That’s the only way it will be solved. It’s not about praying.”

Jack’s Story by Ken Fleming, published by Forty South Publishing, $39.95 is available internationally via stockists listed at jacksstory.com.au and is stocked in Hobart bookstores. All proceeds will be donated to the cause

Originally published as The day after Jack died, Ken sat down in his son’s bedroom with tissues and whisky and started writing to him