Jail is not the solution to youth crime, says Warren Mundine

Locking up kids will not end the youth crime crisis in regional Australia, with work and education the best path forward to close the gap for Indigenous children, a prominent Voice opponent says.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Locking up kids will not end the youth crime crisis in regional Australia, with work and education the best path forward to close the gap for Indigenous children post-referendum, a prominent Voice opponent says.

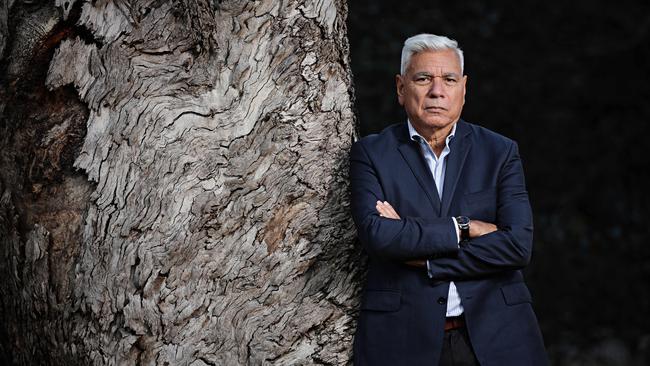

As Alice Springs residents prepared to emerge from a snap three-day lockdown instigated after a wave of violent incidents involving both adults and youths over the weekend, Indigenous leader and former No campaigner Warren Mundine said the only way forward is to focus on “what really works”.

“I’m going to be very controversial about this, but I have found no evidence in my 24 years in looking at this issue that locking up kids actually works,” he said.

“In fact, we’ve found the opposite.”

The restrictions in Alice Springs this week applied to all residents, but a two-week curfew earlier this year only impacted young people.

Mr Mundine said education, economic participation, governance and crime are the four key areas governments must look to make improvement in, meaning states and territories in particular must step up.

“If you lock a kid up, 80 per cent of them you’ve got for life (in the justice system),” he said.

“While if you can put them in a diversionary program, which involves education and work, 80 per cent of them you never see again.”

Mr Mundine said Closing The Gap targets around incarceration rates should be refocused on early intervention and crime prevention.

“If I was in charge of prisons, I could actually solve incarceration rates tomorrow morning – I’d just let everyone out,” he said.

“The real issue isn’t incarceration rates, it is, how do we reduce crime within Aboriginal communities?”

About three in five — or 63 per cent — of young people aged 10 to 17 in detention were Indigenous Australians on an average night in the June quarter of 2023, according to the latest data from the Australian Institute of Health and Wellbeing.

Indigenous children in this age group make up just 5.7 per cent of the general population, making them 29 times as likely to be in detention than non-Indigenous young Australians.

On average the rate and number of Indigenous children in detention has been increasing since September 2020, while over the same period the number of non-Indigenous children has declined.

Last month it was revealed school attendance had improved dramatically in remote Indigenous communities in Central Australia under a funding model the federal government is aiming to roll out across the country.

Since term one the number of children in very remote areas who haven’t attended school for more than 20 days in a row decreased by 88 students.

In response to the snap lockdown in Alice Springs this week, chief executive of Indigenous children advocacy group SNAICC Catherine Liddle said a child and family support hub that offered early interventions would assist in tackling youth crime challenges.

“It could offer early education and care, support for older children to attend school, and connections to other services such as accommodation, therapeutic care, finance, employment, return to country (and) Centrelink,” she said.

Do you have a story for The Daily Telegraph? Message 0481 056 618 or email tips@dailytelegraph.com.au

More Coverage

Originally published as Jail is not the solution to youth crime, says Warren Mundine