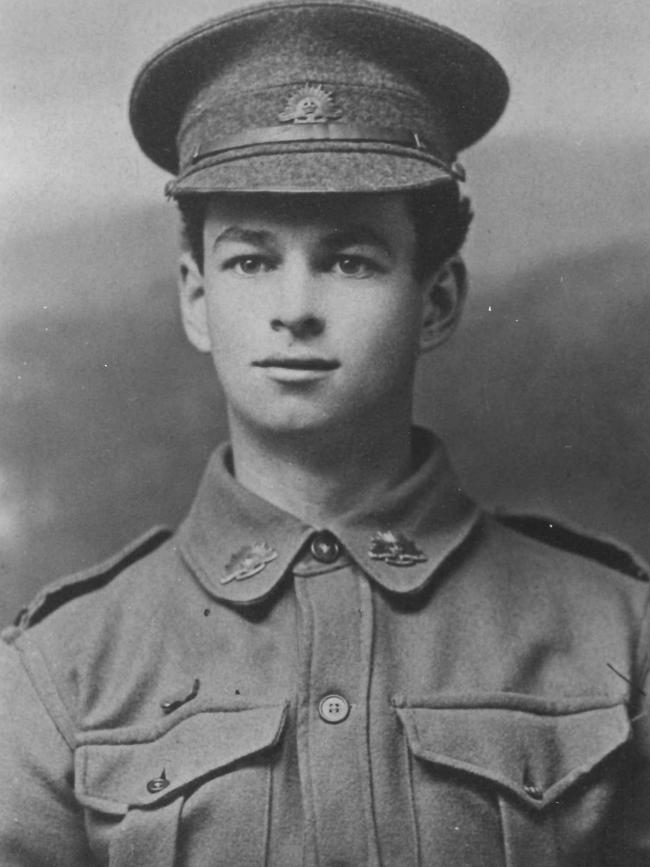

Harold Thomson Smith among seven Anzacs newly identified from the disastrous WWI defeat at Fromelles

Harold Smith turned 20 as disaster unfolded around him in one of Australia’s worst defeats – and he didn’t make it out alive. But today, his family have reason to celebrate.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Aged just 18, North Melbourne’s Harold Thomson Smith volunteered to fight for King and country – his parents signing their approval on his enlistment papers.

As a 19-year-old, in September 1915 he was sent to Gallipoli where he survived three months on the sniper-infested slopes around Anzac Cove, before joining the legendary secret overnight evacuation and the massive redeployment of Australian forces to France.

On his 20th birthday, in his first battle on the Western Front, he fell – shot through the head while working feverishly to dig trenches as one of Australia’s worst military disasters unfolded around him.

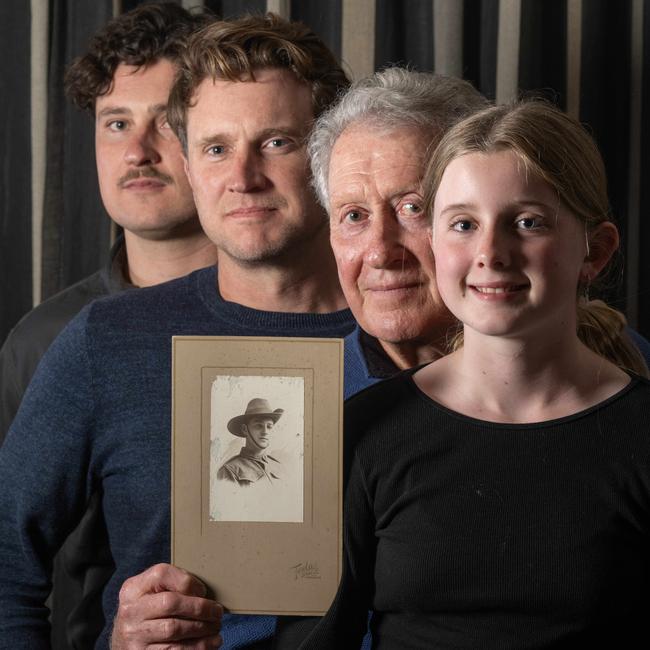

Smith is one of three Victorians and four other Anzacs lost after the Battle of Fromelles in July 1916, who have in recent months been found and identified using DNA testing from living relatives tracked down by researchers; and whose remains, discovered in a mass grave, will now be reinterred in a full military ceremony later this year.

“To hear the news that his remains have been identified is absolutely incredible,” said Ross Stansfield-Smith, the descendant whose DNA enabled the “wonderful, emotional” discovery.

And for the first time, Australians can see his face thanks to a chance discovery by Mr Stansfield-Smith, of Beaumaris, as he sorted through boxes while doing chores.

“My father passed away maybe 15 years ago. I have a lot of old family photos and what have you and I pulled out a box today. And I found a photo of Harold,” the 77-year-old said. “It just blew me away because it was so amazing.”

The battle of Fromelles, on July 19-20 1916, was the Australians’ first major engagement in France and, in the words of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, became “a bloody catastrophe” as Aussie and British soldiers advanced across open country into devastating German fire; then got surrounded and cut off in a counter-attack.

The Anzacs suffered 5533 casualties, among them 1957 killed in action. Many were initially counted as missing; and until the end of the war the battleground – where, in a quirk of history, a young enemy corporal called Adolf Hitler was stationed for a time – remained littered with remains.

As one of the 8th Field Company engineers supporting the infantry, Harold’s job was to dig communications trenches across No Man’s Land as the battle raged.

It was a job done well, as recorded in army diaries of the time. But at some point during the night-time work, the 1.8m-tall Harold “was sniped through the head, death taking place almost instantaneously”, according to a report by his commanding officer.

Harold was one of 250 unidentified soldiers discovered in a mass grave behind Gerrman lines in 2008. A total of 180 Australians have since been identified, with the most recent seven names added to that list officially overnight (Tues-Weds Aussie time) by Matt Keogh, the Minister for Defence Personnel.

Speaking in France, Mr Keogh said of Harold: “To serve in our national identity-forming battles at Gallipoli and to die on the Western Front on your birthday is both the epitome of service to our nation and a demonstration that the ravages of war operate without fear nor favour.”

Along with Chief of Army, Lieutenant General Simon Stuart, Mr Keogh paid tribute to the other newly-identified men: Private George Robert Barnatt, 31, of Launching Place, Vic, who enlisted with and fought alongside his brother-in-law Tom at Fromelles; Private William Christopher Brumby, 29, an Englishman who was working in Sorrento, Vic, before enlisting; and NSW men Corporal Percy George Archibald Barr, 19; Private Ernest Frank Studdon, 31; Private Herbert James Graham, 24; and Private Alfred William Ansell, 29.

And he saluted experts and volunteer groups such as the Fromelles Association who work with Defence to research the cases, find relatives and “make these identifications possible”.

“It is an honour to be able to restore these soldiers’ identities, and know they will now rest under headstones bearing their names.

“Australia does not forget those who serve our nation, and the ongoing work to find and identify our war dead is a testament to this debt of gratitude to them, and to their loved ones.”

More Coverage