Aussie veterans like Paul de Gelder and Alison Creagh reveal what the Anzac legend means to them

Alison Creagh, a member of the Royal Australian Corps of Signals, has shared her personal thoughts to honour the fallen, and her stark reminder of what Anzac Day truly means.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s a day that brings Australians together, but at the same time our responses to it can be uniquely personal.

We invited various prominent Australians to share what Anzac Day and the Anzac legend means to them.

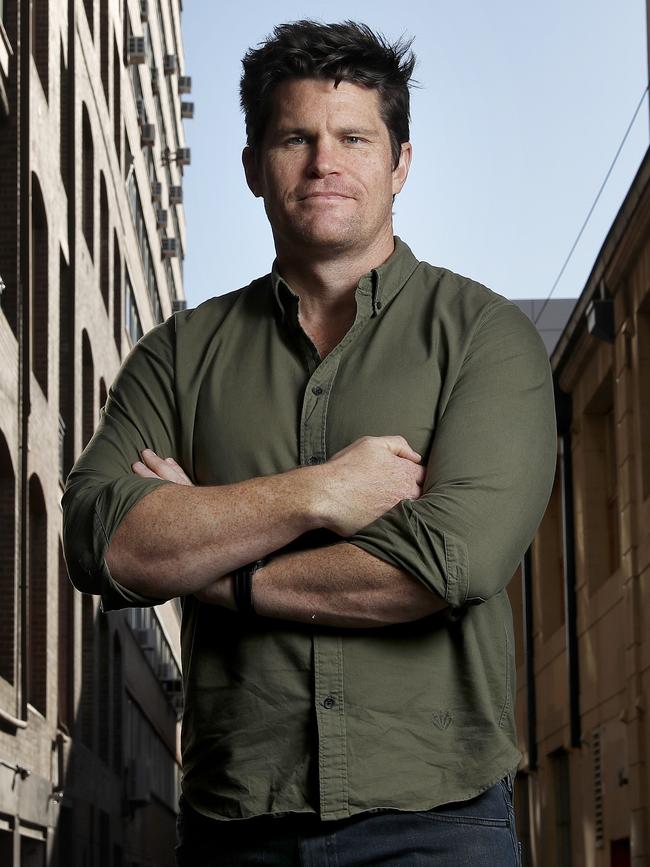

PAUL DE GELDER

Anzac Day is a cornerstone of our nation, a day that carries immense weight for me and,

I imagine, for so many others. It’s a time to pause and honour those who came before us — the fathers, mothers, brothers, and sisters who were willing to lay down their lives so we could live in freedom. Their sacrifice isn’t just a story from the past; it’s a powerful reminder of what holds us together.

For me, the day is all about the Anzac spirit. We hear those words thrown around a lot, but they’re hard to pin down. Maybe they mean something different to everyone who’s served, but to me, it’s about the person next to you. It’s selflessness when the odds are against you, standing by my Infantry and Clearance Diver mates whether we’re out in the field or back home. It’s about living in a way that honours those who gave everything — striving to be the best Australian I can be because of them.

Sixteen years ago, I felt that spirit in a way I’ll never forget. A shark took my hand and tore into my leg, and I genuinely thought I wouldn’t make it out of that water. But my Navy diver

brothers pulled me out and jumped into action, saving my life without a second thought.

That was the Anzac spirit — real and raw. Then, when I lost my leg and things got dark, it showed up again. My family, friends, navy and army mates, even strangers from across Australia — they all reached out. Their support carried me through, and I feel fortunate to

have seen that spirit so many times. It’s what drove my recovery and keeps me pushing forward — not just for myself, but for them. They believed in me, and that’s a fire I can’t let

die.

It hasn’t been easy; in fact, it’s been the toughest stretch of my life. But I accepted the risks when I signed up, and I wear these scars with pride — for my country and its people. I’m not alone in this. Australians have always stepped up to defend this land, and that’s something I feel in my bones. But the Anzac spirit isn’t just for those in uniform. It’s grown beyond the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps to touch every part of our defence forces and

every corner of our lives.

It’s there when you offer a shoulder to someone who’s struggling, when you help someone back up after they’ve stumbled, or when you share a kind word or a selfless act. That’s what it means to me — looking out for each other. And it’s not just soldiers or sailors who carry this spirit; it belongs to every one of us. You don’t need to have faced a battlefield to live it. It’s in the teacher who stays late to help a struggling student, the neighbour who checks in on the elderly couple down the street, or the stranger who stops to help change a flat tire in the rain. It’s the firefighter rushing into danger, sure, but it’s also the volunteer stacking sandbags during a flood or the mate who listens when you’re at your lowest. Every time you put someone else first, every time you lend a hand without expecting anything back, you’re carrying the Anzac spirit. It’s in the small, quiet moments as much as the big ones. When we do these things, we’re not just keeping the spirit alive — we’re weaving it into the fabric of this country. We’re making Australia stronger, honouring those who sacrificed so much, and

showing that their legacy isn’t locked in the past — it’s alive in us, in every civilian who

chooses to stand by the person next to them. That’s how we remember them, and it’s how

we build a future worthy of their courage.

When others forget. We will remember them.

Paul De Gelder is a former navy clearance diver and army paratrooper, a motivational speaker and environmental advocate.

ALISON CREAGH

This year marks 110 years since the landing at Gallipoli during the First World War.

When I march on Anzac Day I will remember and commemorate the service and sacrifice of those who served alongside me and those who served before me.

Many have made the ultimate sacrifice and many bear the scars of service.

For me, seeing flags at half-mast over Coalition Headquarters in Afghanistan honouring our troops who gave their lives on foreign soil, just as Australians did at Gallipoli, was a stark reminder of what Anzac Day truly means.

This year also marks the centenary of the Royal Australian Corps of Signals as part of the Australian Army. The Corps allows commanders and troops to communicate using communications and information systems technology and protect our forces through electronic warfare and cyber operations.

I am a proud member of the Signals community having served in the Corps since I became an army officer in 1985.

More than 107,000 Signallers have served Australia for over a century and I’m immensely proud of this service, and our families who have supported us. A number of our Signals community have died or been wounded or injured as a result of their service.

Anzac Day is an opportunity to recognise this service and sacrifice.

I will pause to remember my family and other families who have supported those of us who serve.

Families like mine bear the burden of losing someone because of their service.

I will also recognise the contribution of men and women in the Australian Defence Force who continue to serve Australia on operations around the world and in Australia, and I will think of our veterans who continue to contribute to Australia.

I will always remember our service women and men and I hope Australians will never forget.

Brigadier (retired) Alison Creagh AM CSC is the President of Paralympics Australia and Representative Colonel Commandant of the Royal Australian Corps of Signals.

CHERISA PEARCE

Growing up, Anzac Day was a bit like Christmas or a birthday. Our whole family would watch my grandfather and father march in the parade down King William Street in Adelaide.

Grandpa served in World War Two, and Dad served in the Vietnam War.

Afterwards, we would visit a local pub where we would meet up with their mates. Seeing the camaraderie between them all was amazing. You could see how much it meant to them. They would bring their kids – and after over 50 years, we are still very close.

The military becomes your second and extended family. In addition to my Dad, my Mum Linda served as an army nurse during the Vietnam days, which is where she met my Dad. My brother Tyson joined the army at 16 as an apprentice and graduated two years later. I was 20 when I attended his graduation and when I looked at what he was doing and compared it to my life as a legal secretary, I thought I needed a more adventure in my life!

After seeing a TV ad for the Royal Military College Duntroon in Canberra, I spoke to my mum about applying.

Both my parents were extremely supportive, as they had very fond memories of the time they served.

There were almost a thousand applicants for Duntroon the year I applied and only 100 were

accepted. I still don’t know how I got in, but in July 1994 I arrived in a very, very cold

Canberra. We spent six weeks at Majura Field Firing Range to do our basic training, living in big tents. One morning it hitting -17 degrees Celsius.

As a Logistics Officer I deployed three times to East Timor. My third tour was in 2006 for six months and I had a two year old and a three year old at the time. There was a lot of judgement from those who have never served, questioning how I could I leave my babies for that long. Interestingly enough, nobody asked the men that same question. Personally, I think it was better deploying when they were so young, they had great support, as we were living close to my parents and a group of Vietnam veteran wives who stepped up to help.

I was medically discharged in 1995 as I was carrying a fair number of injuries. Having

witnessed many veterans struggling with their transition out of the military, I was determined to make it a positive experience. Serving in the military can become your identity and

transitioning can be hard.

Since leaving, I have thrown myself into my local RSL. We conduct the biggest regional Dawn Service in Australia at the beautiful Elephant Rock.

Each year I get told that I am wearing my Dad’s medals on the wrong side and need to

explain that they are mine. One Anzac Day, I was refused entry onto a bus allocated for

veterans. We have come a long way, but more education is needed.

Anzac Day can be a difficult time for some veterans. My advice to those who are feeling

isolated, is to remember that you are not alone. The friends you have served with are there

for you. There are many organisations like the RSL that organise activities to help

reintegrate back into the community. Connection is important and Anzac Day is one way

veterans can reconnect.

So, if you see a veteran, please say hello and ask them about their service. I am sure that

they would love to take the time to talk about their service and their mates … in addition to

getting a funny story or two, you will probably make their day.

Cherisa Pearce served in the Royal Australian Army Medical Corps and Royal Australian Corps of Transport, and is now an RSL Ambassador.

MARK WALES

Anzac Day isn’t just a national ritual — it’s a reckoning.

We have lost more than 100,000 troops to warfare since Federation.

I served 16 years in the military, six of those in the Australian SAS. I’ve led troops into

combat, cleared Taliban strongholds, and carried out missions deep behind enemy lines. I’ve

seen the cost of war. So when the bugle sounds on April 25th, I think of mates who died.

I hope that the long list of war dead does not get any longer.

The real cost of service doesn’t show up in parades. It shows up at 3am when sleep won’t

come. It’s in the marriages tested, the friendships strained, the mental battles fought long after

the guns go quiet.

Anzac Day is our chance to understand that truth.

I watched a mate’s widow and two-year daughter bow and place a wreath for him in the quiet

dark at the SAS barracks in Perth. I doubt there was a single dry eye among many combat

hardened soldiers in the audience.

There are some things worth fighting and dying for, but for me that list is brief. I hope as a

nation we think long and hard before we send our precious sons and daughters to a future

battlefield.

I take my son to Dawn Services now. He’s seven. I tell him it’s about looking after your mates.

I like taking him and I know he realises it’s an important morning and a celebration as well.

I often share my experiences of fighting and what I learned from it. I find meaning in it, and I

get to talk about my mates and bring them to life for an audience. Not a name on a memorial

wall, but as the real people they were. For just a few minutes, for me and a small audience,

they are as alive as they were the last time I saw them. I love talking about them and what

they taught me.

Because the lessons from war — about loss, loyalty, and grit — are too costly to leave behind.

Mark Wales served in the army for 16 years, including four tours to Afghanistan, appeared in Australian Survivor.

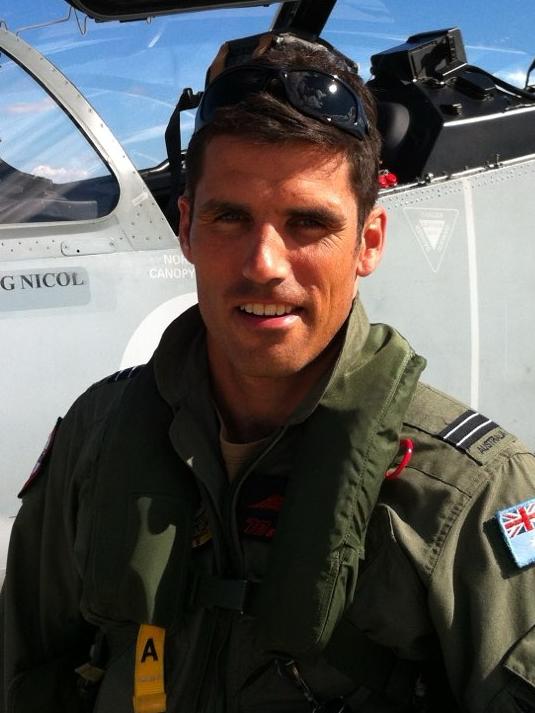

MIKE ATKINSON

I wanted to be a pilot when I saw Top Gun at age 13. Being in the Air Force and Army from 1995 to 2014 was awesome and it gave me so much. Military aviation helped me optimise my brain to perform better under high workload, like martial arts, but for the brain.

My grandfather, a former commander in the Indian Navy, took me to dawn services in Canberra when I was a kid. Later, as a uniformed member I felt conflicted about certain aspects of Anzac Day. I’m not a fan of medals. I’m not saying people don’t deserve them but the Australian way is to not need external validation for being brave or good.

I also found it hard to focus purely on the remembrance aspects, instead questioning some (not all) of the political decisions that caused us to remember more people on Anzac Day than we needed to.

Military aviation is exceptional at analysing performance and debriefing what went wrong so we do better next time. Our political system doesn’t have such a mechanism. I therefore don’t have confidence we are learning from our mistakes.

Don’t get me wrong. Some wars are black and white but some are train wrecks (no disrespect to those who served in these conflicts). The best way to honour those that died in those wars is to promise, genuinely, that we’ll do better next time.

I can hear a chorus of grumpy voices saying “Anzac is not about politics! Leave it out”. Fair call. I understand that point of view. Those that died or were injured did not have a choice. They did what they were ordered to do and made the ultimate, unselfish sacrifice. They underwent hardships greater than I can imagine. We should always remember them.

Mike Atkinson is an outdoor adventurer and former military pilot who appeared in Alone Australia. Follow him on Instagram at @outback_mike.