A Tallent never in doubt: Adelaide racewalker Jared Tallent’s long road to gold

HE stayed the course despite suspecting key Olympic rivals were doping. Now, four years after losing to a Russian drug cheat, Adelaide racewalker Jared Tallent is about to become a gold medallist.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

JARED Tallent wasn’t wearing a heartrate monitor during the 50km racewalk at the London Olympics four years ago.

He reckons if he was, it would have read 180 beats per minute, which is his maximum, when Russian Sergey Kirdyapkin made the race-winning move.

But no monitor can measure the feeling of having your heart ripped out of your chest, which is what happened to the Adelaide-based champion walker as he watched the Olympic gold medal slip away to a man he long suspected was a drug cheat.

Still, Tallent kept going.

His gaze was fixed on Kirdyapkin’s white singlet and blue shorts, which remained a constant 200m in front of him.

It was about the 42km mark when Kirdyapkin left the field in his wake and no matter how hard Tallent breathed, how fast he pumped his arms or moved his legs, he couldn’t go with him.

Cruelly, the race was held on a 2km circuit, which meant for the final 8km they crossed paths four times, and each time was like a dagger through Tallent’s chest.

“I could see him in the distance, it was quite crowded on the course and we were lapping a lot of people who were blowing up,” Tallent says.

“He would have been about 200m ahead and in the back of my mind I thought it was most likely I’d been beaten by a drug cheat, but it’s something I was used to over a long time.”

To that point, Tallent had executed his race plan to perfection. He wanted to be ultra-conservative early and then come home hard.

“I had a really bad experience in 2009 when I pushed too hard between 30km and 40km and blew up in the last 10km,” he says. “So I was really trying to pace myself. It was probably the biggest lead pack there’d ever been at a major race and I was feeling really good.

“I was at the back of the group, maybe sometimes five seconds off, and the Chinese guy who came third (Si Tianfeng) went off the front at 35km and one of the Russians chased him but Kirdyapkin stayed in the group.

“It wasn’t until just after 40km that a lot of the group blew apart. From what I remember Kirdyapkin went off the front and I came through but just never got on to him. It was around 42km and he was gone. I chased as hard as I could but he just pulled away. At 45km, I thought I’m probably not going to get him because every time you go around the turn you could see him coming back the other way.

“And every lap he was getting further ahead, each time the gap was bigger and I was doing as much as I could but...”

Leading into the London Olympics Tallent had revolutionised his training and pushed himself harder than ever. At a world cup in Russia earlier that year he had finished third behind two Russians including Kirdyapkin.

“After that race we went and had a re-think of what sort of training and preparation I would need to do to be more competitive,” Tallent says. “I definitely trained the hardest I’ve ever trained. Leading up to other events my long run would be 40-45km in the morning and I would occasionally go out in the afternoon and do 10km at an easy pace. But we thought I had to be stronger in that last 10km so we came up with the idea of going out and doing 10km at tempo or threshold pace after 40km in the morning. Leading up to the Olympics I did that four times and they were massive days. By the end of the day I was absolutely wrecked.

“I was actually thinking whether it was bad for my health because I would finish the afternoon session doing 10km as hard as I could and I’d be in pain for the rest of the night and found it really hard to sleep. I just really hoped when I got to London that it would make a difference - and the last 10km I accelerated and it was actually the quickest 10km split I’d ever done in a 50km race.

“And it still wasn’t good enough.”

Tallent grew up competing in athletics in Ballarat and it wasn’t so much that he found walking as walking found him.

Early days he would win both the racewalk and distance running event on Friday nights but at the regional championships he was constantly denied a chance to compete at state level by schoolmate Collis Birmingham who went on to run the 5km at both the Beijing and London Olympics.

But Tallent could still win the walk and that led to a scholarship with the AIS in Canberra, which is where he met his future wife Claire Woods, an Adelaide athlete who became Oceania champion and Commonwealth Games silver medallist. The pair married in 2008 and Claire is now retired but still coaches Tallent in one of Australian athletics’ great partnerships.

While racewalking might seem like a foreign sport to many Australians, there are only two rules for competitors. They must have one foot on the ground at all times and the leading leg must be straight when it touches the ground.

“I don’t find it hard, training every day and doing 200km a week, I picked up the technique as a junior,” Tallent says.

The result is anything but walking pace. Jared’s average race speed over 50km is about 14km/h which equates to 4min 19sec per kilometre – a result many City-Bay Fun Run joggers would love to achieve. He estimates the average person would walk at 6km/h. The leaders in the 50km walk normally go through the 42km point (the distance of a marathon) in right on 3 hours, which is the magical barrier many amateur runners try to break.

He had only been competing for two years when he watched the heartbreaking moment Jane Saville entered the stadium in Sydney and was disqualified just moments from winning gold in the 20km at the Sydney Olympics.

Tallent has only been DQ’d once – at the 2007 world championships – which forced him to correct his technique and the following year he won a silver and bronze medal at the Beijing Games.

“Afterwards (2007), I came home and did a lot of work with Claire and really tried to iron out the kinks in my technique, we did a lot of video work for months and months and that obviously paid off when I got to the Beijing Olympics,” he says of the Games where he won bronze and silver.

On the morning of the race in London, Tallent woke up feeling confident. But he knew the dark shadow that hung over his sport was still there.

“My preparation had gone really well but I always knew it was going to be extremely hard to beat the Russians,” he says.“For years and years they’ve (Russians) had positive results and before Beijing, five guys that Kirdyapkin trained with had tested positive to EPO.

“He only got to race at the Beijing Olympics because two of the other guys in the 50km that he trained with tested positive.”

But as he had done his entire athletics career, Tallent walked on defiantly.

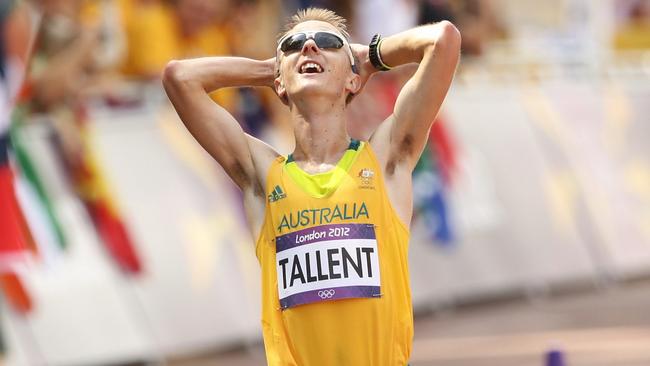

When he crossed the finish line in London the clock said 3 hours, 36 minutes, 53 seconds. He had been robbed of the gold medal and a lifetime of hard work by 54 seconds.

At that moment Tallent fell to his knees and with hands on head looked at the sky. Was he celebrating silver or ruing a lost gold?

“At that stage it was an Olympic medal, I had my family in the crowd and Claire’s family was there, too. It was taking in the moment,” he says.

Later, Tallent stood on the podium next to Kirdyapkin but they didn’t talk. The racewalking community is a tight one, but that doesn’t extend to everyone according to Tallent.

“I smiled on the podium and shook his hand but those guys, we don’t ever really speak after a race,” he says. “The walk community is quite small and we see a lot of guys at competitions, we’ve got a lot of friends, but the Russians are never at those events.”

It would take three years for the charges against Kirdyapkin to be announced publicly and in that time Tallent’s feelings about the result in London began to change.

At the 2013 world championships in Moscow he says the top Russians from London were withdrawn in the week of the race amid reports they were either sick or injured.

“It was just way too suspicious,” Tallent says.

As more and more Russians were banned for doping offences, Tallent began to speak publicly about the situation as his disappointment turned into anger.

But even then it still felt like no one really cared.

“We were annoyed at how the coach (Viktor Chegin) was still allowed to coach, there were a lot of positive results,” he says. “That’s when me and other athletes got very vocal on social media and stuff and were extremely frustrated that nothing was done.”

In November 2015, Kirdyapkin was handed a three-year, two-month ban that dated back to October 2012, by Russia’s anti-doping authority. But it would be up to the Court of Arbitration for Sport to rule on whether he would keep his Olympic gold medal after the IAAF appealed the Russian decision.

Tallent was at home with wife Claire in Adelaide on the night of March 24, 2016, when he got an email from AOC President John Coates advising him that an announcement was pending. The CAS ruled that all competitive results by Kirdyapkin from August 20, 2009 to October 15, 2012, were now disqualified.

And in that moment, Tallent was Olympic champion. “We had a bottle of wine in the fridge so we celebrated with that,” Tallent recalls. “And then the next day we were off overseas for a training camp.”

Three months later and the one thing that truly defines an Olympic champion – a gold medal – will be presented to Tallent at a special ceremony in Melbourne next Friday, June 17.

He has invited 150 family, friends, coaches and supporters to join him on Treasury steps before the Australian Olympic Committee and Athletics Australia hold a special function to celebrate.

“I’ve been away for a few months and had races to think about, we got home (last week) and when I start to write the speech I’ll be able to think a lot more about it,” Tallent says.

“The main thing will be thanking all the people who helped me get to that point and who were involved in the lead-up to London. I don’t want to dwell too much on how it’s happened, I want to celebrate the fact that I am now Olympic champion.”

“It’s really good it’s happening now because it means a lot to me to have the medal before I go to Rio. It would be so disappointing to be in Rio and still not have it.”

With two months until he competes in the 20km and 50km events in Brazil, in his third Olympics, Tallent is confident the sport is in a much better place than it was four years ago.

Athletics was rocked last year by a World Anti-Doping Agency report into a systematic doping program involving Russia’s track and field athletes which led to calls for the nation to be banned from competing in Rio.

“Generally speaking I’d say 95 per cent of the field or more is clean,” Tallent says. “There are only question marks over a few and it’s going to be a hell of a lot cleaner, but it’s still going to be really tough (to win).”

But the 31-year-old has no plans on hanging up the walking shoes after Rio.

“I love the training camps and training here in Adelaide, I’ve got a lot of friends in the sport and there are a lot of events to go to,” he says. “As long as I’m still doing good and enjoying it I’ll go to Toyko and see from there.”

As for what he’ll do with his newest and most prized possession, Olympic gold medal, that’s going straight to the pool room – in Canberra.

“All my Olympic medals are at the AIS in Canberra so it might be good to keep that going and have it there,” he says. “They get heaps of school groups through and the medals are on display. My silver medal is next to Libby Trickett’s gold medal so it might be nice to have two gold medals side by side.” ●

Originally published as A Tallent never in doubt: Adelaide racewalker Jared Tallent’s long road to gold