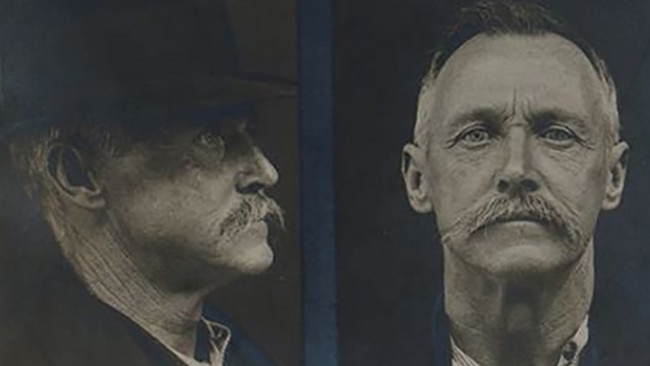

The life and death of Melbourne’s first great safecracker

HE could break any safe and even outwitted early fingerprint technology. But in the end, John Jackson couldn’t beat the noose.

Law & Order

Don't miss out on the headlines from Law & Order. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Extract: Ned Kelly’s dangerous mum

- Extract: Inside an SOG raid

- Extract: Cold war games at the Melbourne Olympics

WHEN it came to safecracking in the early 1900s, one man was regarded by the police as a master of his craft, Melbourne’s John Jackson, whose first conviction was his last.

In June 1907, along with offsider Patrick Hegarty, he had been suspected of a robbery at the Victoria Mint when some £1300 of gold was taken.

In early 1912 Jackson and Hegarty were again arrested, this time over a robbery at the jewellers Webster & Cohen in Little Collins Street. In the first case in Victoria in which fingerprint evidence was accepted, Hegarty received seven years but Jackson was released.

In May that year Jackson went on trial for the January 1905 jewel robbery at Ayres, Henry and Co in Swanston Street.

Three safes had been cracked and watches stolen but on the face of a watch left behind was a thumbprint, which fingerprint expert DS Lionel Potter and Inspector Childs from New South Wales said was Jackson’s.

He was fortunate, though.

Jackson had no convictions and he did well with the jury, producing a magnifying glass to examine the prints and telling them how he made his money gambling and had never been in the shop. He also did well with the judge, who told the jury that they had to be sure that Potter was right about the print.

It would, he said, be very hard to convict a man on a print taken seven years earlier. Jackson was acquitted.

His last great success was probably the ‘Eight Hours Day’ robbery at Melbourne’s Exhibition Building. The takings at a union carnival, said to be between £300 and £400, were deposited in a safe at the nearby Trades Hall on 26 April 1915, and stolen during the night.

Apart from taking the money the thieves had helped themselves to biscuits, cheese and wine. No charges were brought.

It was generally thought that with Hegarty doing time, Jackson’s new helpmate was Richard Buckley.

Buckley had been sent to the Jika reformatory at the age of fifteen and from then on it was one sentence after another until December 1883, when he was sentenced to four years and ordered to have three whippings — one on the first, third and sixth month of his sentence.

His conviction for robbery was later quashed but he received no compensation and was an embittered man.

Quite what induced Jackson to go in on another robbery at Trades Hall is a mystery.

He should have been comfortably off for the present and he was always the number one suspect for any quality job that went off in the city.

Perhaps he had come to believe that at the age of fifty-one he was inviolable.

But, on 1 October Jackson, Buckley and Alexander Ward burgled the Trades Hall, stealing £30 from the safe.

In a bungled police swoop at the time, a passage light was switched on in the Trades Hall, leaving Constable David McGrath exposed.

Twenty-six shots were fired and McGrath was killed. In the upstairs hall at Trades Hall, bullet holes can still be seen in the walls from the 1915 shootout.

Jackson, who claimed he had fired in self-defence, was convicted at the first trial but, with Squizzy Taylor’s interference, two juries disagreed over Ward and Buckley, the latter’s defence being that he had merely fired in the air as a warning.

On the third trial, Ward and Buckley were finally convicted of committing a felony and received five and six years’ hard labour respectively. After his release Buckley became a Taylor stalwart.

At Jackson’s appeal on 17 December his counsel argued that when he came face-to-face with McGrath the officer shot him through the leg and, as he was about to shoot him again, Jackson had aimed at the officer’s hand or arm but had instead fatally shot him.

It was not a promising argument. There was never going to be a reprieve. His solicitor Nathan Sonenberg offered to put £100 of his own money to try to take things to the Privy Council but Jackson asked him to give it to Jackson’s wife instead.

He was hanged at the Melbourne Gaol rather less than 200 yards from the Trades Hall.

James Cosgrove, serving ten years commuted from the death penalty for a 1909 rape, acted as executioner, so receiving a partial remission of his sentence.

This is an edited extract of Gangland Oz: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow by James Morton and Susanna Lobez, out now from MUP. RRP $29.99, ebook $13.99.