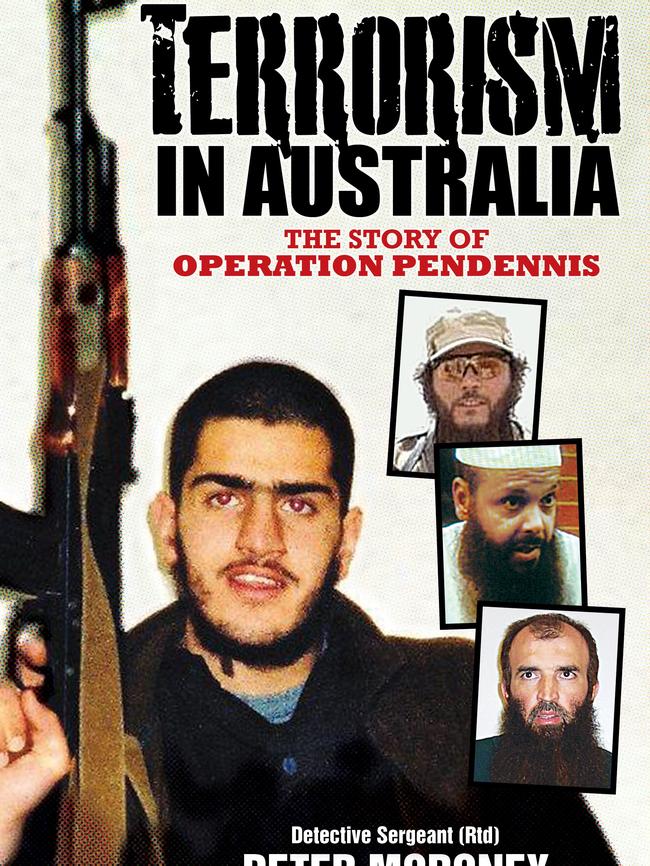

Operation Pendennis: Inside Australia’s most significant counter-terrorism operation

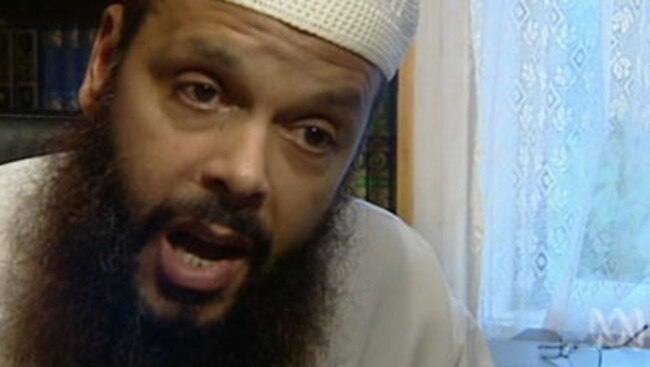

WHEN Islamic cleric Abdul Nacer Benbrika began radicalising young men in Victoria and NSW, police Operation Pendennis began. Retired detective Peter Moroney takes us inside Australia’s largest and most significant counter-terrorism operation.

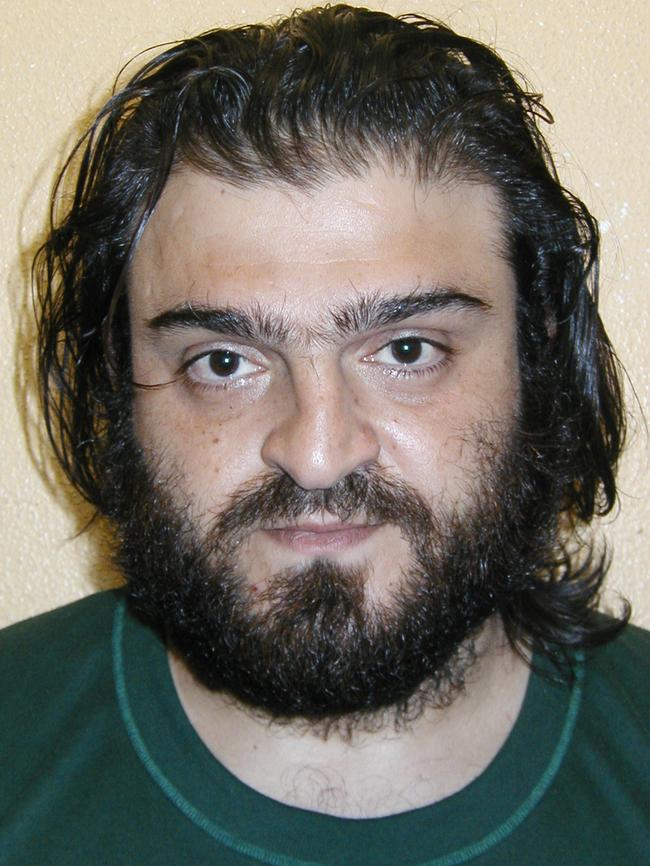

WE thought we caught a break late in the night of 29 August 2004. Under the cover of darkness and unannounced, Abdul Rakib Hasan, Mohamed Ali Elomar and Moustafa Cheikho slipped out of their houses.

They travelled to Melbourne and straight to Ahmed Raad’s residence. The three of them walked inside where they remained for the next few hours.

They all then departed and drove to Abdul Nacer Benbrika’s residence. It was already clear that Benbrika was the head, the leader.

INSIDE AUSSIE TERRORIST NEIL PRAKASH’S PRISON REALITY

AUSTRALIA’S MOST WANTED TERRORIST REVEALS HIS JIHADI BRIDES

The men were identified and, in my view, indoctrinated and to various degrees groomed over a period of time. That’s certainly not saying they were easily led, no. The men knew what they wanted, and they knew Benbrika, religiously, was the one to help them.

Whilst Benbrika would provide sermons that contained an amount of rhetoric at the Islamic Information and Support Centre of Australia in Melbourne, they were by no means over the top.

However, it was whilst he was with both the New South Wales and Victorian jemaah (group), away from the public, that he was encouraging the attendees to move towards a violent jihad. The reason for this was that Benbrika wanted destruction of the kuffar (non-believer). Benbrika also wanted the Australian Government to withdraw Australian forces from Iraq, as their presence was seen by Benbrika to be oppressive.

The men arrived at Benbrika’s. They walked in and greeted each other in an embrace. They took a seat as they were provided with tea.

The men stayed for several hours, and as quickly as they arrived, they departed.

The men walked from the house, but Benbrika was carrying an item that was placed on the rear seat of the car. It was difficult to identify the item. Real surveillance is not like the movies.

The vehicle travelled back over the border into NSW. A decision had to be made whether to stop them or not.

Victorian surveillance brought them to the NSW border and our guys took over.

They were tracked along the Hume Highway and as they approached Sutton Forest, near Mittagong, in the Southern Highlands south of Sydney, they were pulled over.

Moustafa was at the wheel. He began to fidget as the police approached. Elomar uttered a few words of Arabic and it quietened him, but the sweat started to fall from his brow.

‘Calm down,’ quipped Elomar.

Moustafa was quiet, but there was something about him that couldn’t be trusted.

We’d established that in 2001 he had attended the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) camp in Afghanistan to be trained in the art of terrorism war.

LeT, which translates to mean ‘Soldiers of the Pure’ is reportedly one of the largest Islamic militant groups in the world. They predominantly reigned from Pakistan and trained young Islamic fighters in various aspects of war. LeT is now listed within Australia and several other nations as a banned terrorist organisation.

The highway patrol officer walked up to Moustafa and requested he step out of the car.

‘What for?’ came his contemptuous reply.

Moustafa had no time for law enforcement, particularly female law enforcement.

‘Please get out of the car, now!’

The police had been briefed about who they were dealing with and the senior constable wasn’t going to take a backward step.

Moustafa stepped from the car and stood facing the police.

‘Where are you going?’ asked the officer.

‘We’ve been to Canberra, we’re just heading home.’

The police knew this wasn’t true.

‘We’re trying to buy a boat,’ Moustafa added.

The police directed him to step out of the vehicle and open the boot. Moustafa walked to the rear of the car and opened it. The boot contained camping gear that was new and unused.

The officer noticed that there was also a yellow pages in the boot. It was for Victoria. The officer didn’t want to spook them any further and they were sent on their way shortly afterwards. There were no obvious items sighted on the back seat.

The fact that they had lied about where they had come from was some confirmation that they were trying to conceal where they had been. We knew full well they hadn’t been to Canberra.

We felt like we were chasing our tails.

It was clear the trips to Melbourne were of such significance that they dared not risk any communication that could be detected. They had to speak in person.

There was an increase in activity of various members of the NSW and Victorian groups trying to obtain jihadi training material from each other, and downloaded from the internet.

Benbrika was guiding the group and enforcing the need to be committed to the cause and undertake as much training as they could. Some of us suspected that the purpose of the training was for them to advance their skills to be able to successfully wage a violent jihad.

We had nothing concrete to base that on, but it made sense.

If the end goal was a terrorist attack of such power as to try and unsettle the Australian Government to the point of withdrawing troops, then they needed to train, they needed to be ready.

Benbrika encouraged the group, particularly in the art of knife combat. In his view, it was beneficial to their pursuit that the members were trained in the art of knife fighting so that they were proficient in killing the kuffar. Benbrika even demonstrated to another man how a knife could be used to attack and kill a person before adding, ‘You have to learn it.’

During our jurisdictional briefings it was clear that the Victorian jemaah were more advanced than their NSW counterparts. This caused the Victorian Joint Counter Terrorism Team (JCTT) to also step up — they needed to undertake action to disrupt the group.

So it was decided that on 17 September 2004 they were going to knock over Amir Joud’s residence. They would often consult with us and vice versa.

Whilst the two jemaahs were largely independent of each other, Benbrika linked them. Given that Benbrika was the religious head, the chances of him housing anything that was going to be used for any terrorist attack in his own residence were not thought to be high.

On the other hand, the Victorians knew Joud was eager to please Benbrika and stamp his mark. He was more likely to be doing activities to gather information about bomb making and methods of attack.

IN the early hours of 17 September 2004, Joud’s house at Hoppers Crossing was raided. Police removed computers and a host of other material. When it came time to examine the computers, police located a large number of instructional documents, which included the step-by-step guide in how to manufacture and deploy improvised explosive devices, various firearms and other weapons.

The police in Victoria recognised that one of the documents had a detailed section on weapons caching. The document went into elaborate details about how to store weapons and ammunition using PVC piping, and then to slip on end caps to seal it.

As the police read the document their stomach sank. There was no legitimate reason that the Victorians could think of as to why Joud would have such a document.

The Victorian JCTT had successfully broken into Benbrika’s residence whilst he was not home and secreted several listening devices. This was an imperative if they were going to try and stay ahead of him and the group. It was also invaluable to us in Sydney.

On the morning of 24 September 2004 Benbrika was at his home. Abdullah Merhi came to see him.

The young guys involved in the Victorian jemaah would often visit Benbrika, either together or on their own.

Benbrika and Merhi spoke at length about Islam. The police were at the other end of the device, listening intently, desperate not to miss anything.

Sure, they had it recorded and could review it later, but knowing already the type of material that was on Joud’s computer, every word was important.

After some time the conversation shifted to a Muslim’s obligation for jihad and the discussion of terrorism.

Benbrika, sitting opposite Merhi, leant forward slightly, looked at Merhi and encouraged him that if he was to do something, to not kill only a few people, he must ‘do a big thing’.

Merhi responded, ‘Like Spain?’

Benbrika continued. His words were strong, his words were direct and he was encouraging the killing of a large number of Australian people.

The police who were monitoring placed their hands to the headset and turned to look at each other, knowing what it was they had just heard, but disbelieving.

The reference to Spain was a reference to the Madrid train bombings that occurred earlier in March 2004. The explosions aboard several commuter trains claimed the lives of 192 people.

Only a few days later Fadl Sayadi and Joud were with Benbrika at Benbrika’s house.

Joud was becoming annoyed, frustrated with the group in Victoria, and more to the point with Benbrika.

During their conversation the concept of terrorist acts was discussed. Joud piped up with some enthusiasm in his voice and he suggested to Benbrika that if he ‘did not prepare something’ that the boys would move on.

Benbrika was not happy with being challenged.

There was an overwhelming sense within the Victorian JCTT and among ourselves that neither group quite had their stuff together — yet!

There were some conversations and documents that demonstrated what one could only describe as an unhealthy interest in researching terrorism and guerrilla-style tactics, but as far as the capability to pull it off went, they were premature.

However, there was concern that if they got themselves organised things would move very quickly.

Victorians Benbrika, Joud, Merhi, Raad and Sayadi were convicted of being members of a terror organisation. Only Benbrika remains in jail.