The astounding life of bushranger Captain Moonlite

A PREACHER turned gentlemanly bank robber, hanged as a murderous bushranger, Captain Moonlite had another side — his love for a young male gang member.

Law & Order

Don't miss out on the headlines from Law & Order. Followed categories will be added to My News.

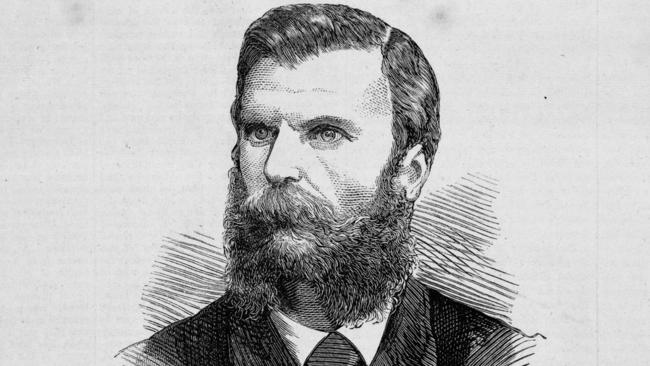

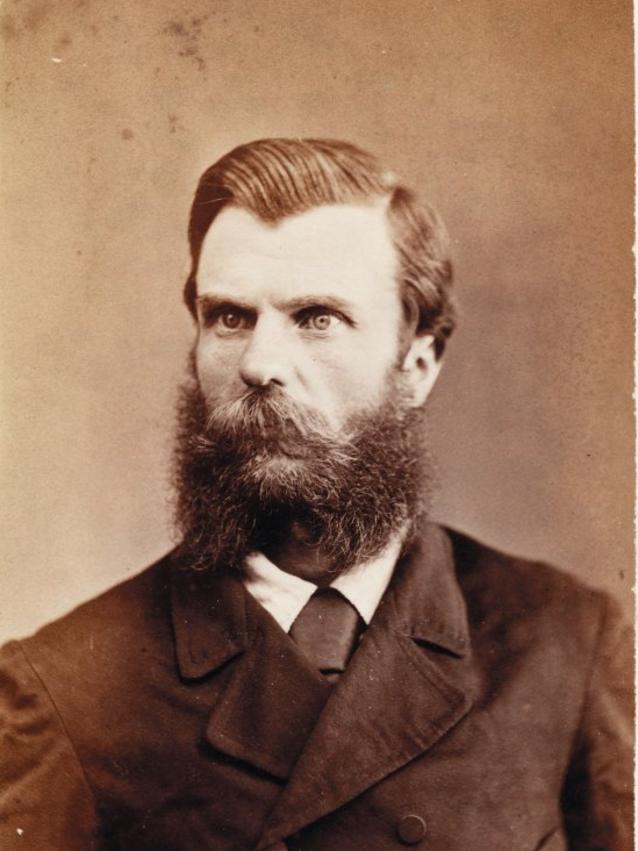

A PREACHER turned gentlemanly bank robber, committed to a lunatic asylum and later thrown in prison where he made a daring escape — this was this astounding life of bushranger Andrew George Scott, known as Captain Moonlite.

But it was his close relationship with young male gang member James Nesbitt, their intense affection through letter-writing and Moonlite’s pain in mourning after Nesbitt’s death that reveal another side of the bushranger — he may have been gay.

Born in Northern Ireland in 1842 Scott migrated to New Zealand as a child where his father was a man of the cloth.

Scott himself became a lay preacher when he moved to Australia in unclear circumstances. He took up residency in Mt Egerton near Ballarat, Victoria, where he made sermons at the local church, attracting dozens of parishioners with his charm, intellect and style.

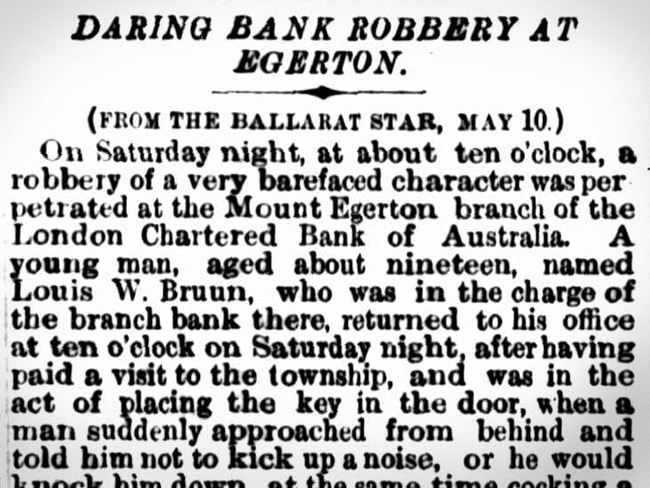

That’s when he parted from religious teaching and staged a daring robbery of the Mount Egerton branch of the London Chartered Bank of Australia in 1869.

Nineteen-year-old Louis Bruun was returning to his office in the bank when Scott sidled up and put a gun close to his head.

Bruun was told to hand over all the money, gold and sovereigns in the bank by Scott, who had covered his face with black.

But the robber’s cool demeanour and insistence that money belonging to Bruun himself be left behind, since he “did not want to rob (Bruun), but the bank” was the start of his legendary gentlemanly reputation.

Scott even offered Bruun a drink and the smoke of a pipe.

As reported in the Ballarat Star on May 10, 1869, the pair later went to a schoolhouse where a declaration was written by the bushranger to absolve Bruun:

“I hereby certify that L. W. Bruun has done everything in his power to withstand our intrusion and the taking away of the money, which was done with firearms.”

He then signed it, ”Captain Moonlite.”

With that, he left Bruun tied up and made off with the bounty — more than £1000 in coins, notes and valuables.

Bruun and Scott knew each other prior to the robbery and Bruun told authorities he thought the robber sounded like Scott.

Suspicion fell on the former preacher, who soon made off to Fiji and then returned to NSW a while later, funded by his loot, some of which he deposited in a bank in Sydney.

But his life of trouble continued as he feigned gentlemanly standing in NSW. He was at one stage put in Parramatta lunatic asylum, but it is believed he was faking insanity.

Upon his release in 1872, the Mt Egerton bank robbery caught up with him. Moonlite was arrested and put in jail, only to scrape a hole through to an adjoining cell and stage a breakout with several other inmates.

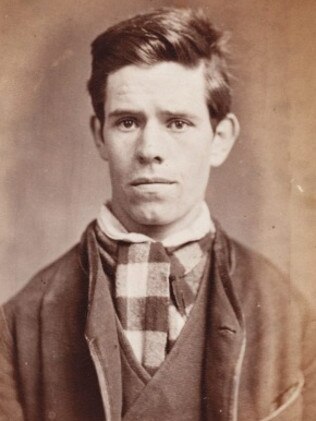

But he was rounded up again and sentenced to more time in Pentridge. That was where he met James Nesbitt, a 21 year-old who became his closest friend.

On Moonlite’s release in 1879 the pair shared a house in Fitzroy and became inseparable, as Moonlite tried to make money by exploiting his public image through a series of lectures.

When that failed, the pair recruited young gang members and became bushrangers per se, committing robberies in rural towns and sometimes being mistaken for the Kelly Gang, which was also active at the time.

The final straw came with the desperate holdup at Wantabadgery Station near Wagga Wagga where the gang had sought work and shelter after almost starving in the bush.

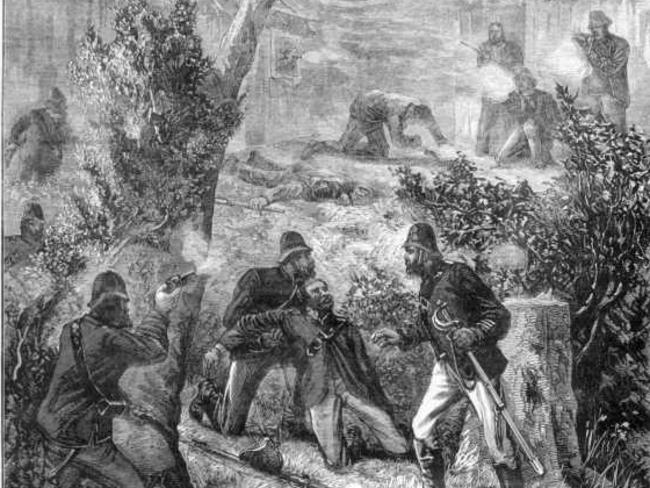

Twenty-five hostages were taken in a nearby hotel and when police troopers arrived the armed gang held them off for hours before escaping and bunkering down in a farmhouse.

By now police had returned in greater numbers and the gang were in the depths of desperation.

James Nesbitt ran outside, attempting to lead police away from the house so Moonlite could escape, but was fatally shot in the head.

As one account puts it, as James lay dying, Moonlite “wept over him like a child, laid his head upon his breast, and kissed him passionately”.

While deep in grief in prison before his execution, Moonlite wrote of his love or Nesbitt, “the man with whom I was united by every tie which could bind human friendship, we were one in hopes, in heart and soul and this unity lasted until he died in my arms.”

Although historians are divided on the exact nature of their relationship, the overt romance of their friendship has led many to believe they were in love.

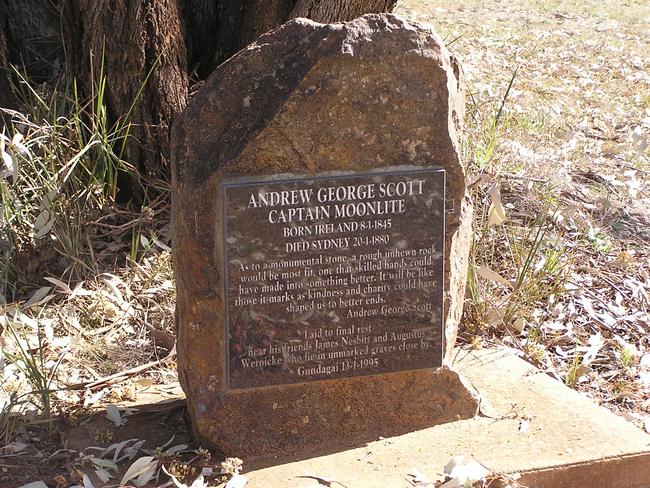

Moonlite was hanged on January 20 1880, wearing a lock of Nesbitt’s hair fashioned into a ring. A request to be buried next to Nesbitt in Gundagai wasn’t granted and he was interred in Rockwood Cemetery in Sydney.

In 1995 there was a successful petition for Moonlite’s body to be exhumed and taken to Gundagai to lie next to Nesbitt and fellow gang member Augustus Wernicke, who also died in the police shootout.

In one of his last letters, Captain Moonlite wrote a description of the tombstone he wanted for his gang, which is now inscribed at the grave: “As to a monument stone, a rough unhewn rock would be most fit, one that skilled hands could have made into something better.

“It will be like those it marks as kindness and charity could have shaped us to better ends.”