How online trap snared one of world’s worst paedophiles

TO others online he’d just been an avatar on a screen. But cops knew exactly who he was — the head administrator of the world’s biggest paedophile network. And raiding his home was just the beginning.

Law & Order

Don't miss out on the headlines from Law & Order. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SHANNON McCoole woke in the late afternoon, his bedside electric alarm clock letting him now the light was fading outside. Still half-asleep, he negotiated his way past a mound of clothes on his bedroom floor and around a box overflowing with empty Crown Lager bottles. Dirty dishes were stacked in the sink, the spare rooms filled with junk, a step-up machine stood gathering dust.

Outside the low-set south Adelaide home, his Volkswagen four-wheel- drive was parked in the driveway. It looked just like any other home in the street, and this was just like any other day for McCoole. He had a night shift ahead but first, as always, he checked into his online life.

On the loungeroom table, his laptop whirred into action. A few rapid keystrokes would unlock a portal to the so-called dark web, the internet world invisible to search engines such as Google. Lightning-fast electronic relays flashing through thousands of computer servers around the globe would conceal his identity. He could be anyone, anywhere.

A knock on the door drew him away from this virtual world. A detective stood outside, and after McCoole opened his door several others rushed in.

McCoole’s online identity had been a secret, known only to him. To fans and enemies alike, he had just been an avatar on a screen and an invented four-letter name: NUKE. Until now.

The police swarming his home knew exactly who he was: the head administrator of the world’s biggest paedophile network, a 45,403-member website we’ll call the “KidClub”. [The name of the site and usernames mentioned in this story have been changed for legal reasons.] His messy home was its global HQ.

The raid on one of the world’s worst paedophiles was just the beginning. Less than 24 hours later, police would set in motion an audacious plan. Queensland detectives instrumental in McCoole’s arrest planned to take over his online identity. For the first time, police would be running a dark web paedophile network, using their unique position to pick off its faceless upper echelon one by one.

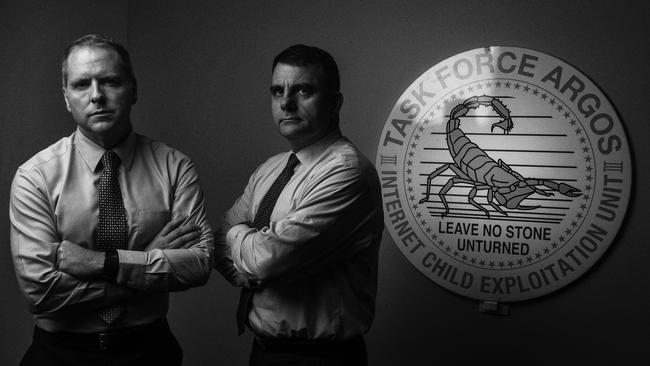

HOW McCOOLE WAS IDENTIFIED IS AN extraordinary story of detective work, centring on a dedicated group of police whose efforts transcend borders. Task Force Argos is Queensland’s internationally lauded child-protection squad. Its roots go back more than 20 years, to its previous incarnation as the Child Exploitation Unit. In 1996 it officially became a task force, charged with investigating allegations of historical child abuse. Its name comes from the all-seeing giant of Greek mythology and it adopted as its motto “leave no stone unturned”, its insignia a scorpion, natural predator of rock spiders.

By 2000, the internet was starting to feature in abuse cases, with paedophiles gravitating online to network and share images. Back then, Detective Inspector Jon Rouse, now 52, was new to the squad and set up a team of three to conduct online investigations. Today, he’s the veteran officer-in-charge and almost all investigations are internet-related, whether it’s men grooming children online or exchanging videos and photos via encrypted computer networks. Based on the first floor of Brisbane’s Roma Street police headquarters, Argos has notched up a slew of successful operations that have rescued children from harm. But no operation has been bolder than the arrest of McCoole and takeover of his identity.

The journey down the winding path to McCoole’s door had begun five years earlier, when Canadian police began investigating Toronto-based Azov Films for selling “artistic” videos of naked boys. Operation Spade, as it became known, unearthed a trove of customer information, including computer IP addresses and credit card details, and passed them on to global policing agencies. More than 30 Queensland customers, including four teachers, a lecturer, nurse and bank manager, were arrested in June 2013. One of the arrests would become pivotal in the later investigation of McCoole.

It was the end of a busy day of raids when Argos Detective Senior Constable Libor Joch knocked on the door of an Azov Films customer in Banyo, on Brisbane’s northside. There was no answer, but Joch decided to wait at the front door while he phoned for approval to gain entry. After a long wait, Joch got the go-ahead, and the moment he entered, the home’s missing resident emerged from the bushes outside – he had been there all along, watching police. Inside, Joch found a dark, derelict lair.

The house had no electricity, so its occupant had rigged up some cables from a nearby shed to power his computer and appliances. Along with the discovery of a huge library of child-abuse images, Joch made another breakthrough: the customer held a VIP account with a burgeoning dark web paedophile site, the KidClub.

Argos and its international counterparts had suspected since 2011 that an Australian was running the KidClub under the name of NUKE – online posts and seized material had indicated as much. But almost nothing was known about his identity. The arrest of the Banyo VIP member gave Argos their first “in”. Hoping to reduce his sentence, the man gave his KidClub login to Argos. To join, members had to post videos or photos of hardcore pre-teen pornography.

Joch, with approval from Rouse, took over the VIP’s identity and began to harvest material and document crimes. Argos was inside the site, but at this stage McCoole was not on the radar.

Members accessed KidClub by using Tor encryption software, which conceals a user’s identity by routing them through a worldwide volunteer network of more than 6000 computer servers before delivering them to their final destination. This complex chain renders it impossible to trace the IP address of the original computer. Tor stands for The Onion Router (so named for its layers of privacy protection) and was developed by the US Navy to protect government communications. It became popular among political activists, but for obvious reasons is also supremely attractive to privacy-conscious paedophiles.

At the same time Joch was infiltrating the KidClub, US authorities were making major inroads into the dark web’s criminal underbelly. In July 2013, an FBI investigation shut down Freedom Hosting, the hosting service for most Tor child-abuse websites. Eric Eoin Marques, 28, from Ireland, was arrested and accused of being “the largest facilitator of child porn on the planet”. The KidClub and similar sites vanished overnight as the host was shut down.

But like the mythical Hydra whose severed head is replaced by two, KidClub came back stronger than ever. It relaunched and benefited from the fact that its major competitor – a dark web site called Lolita City – was under major attack from hacktivist group Anonymous, trying to shut it down. The resultant disruption saw users flee to KidClub in droves. It was soon the biggest child exploitation network in the world and Argos’s detective Joch, with his VIP membership, had a ringside seat. Predator was about to become prey.

VIP status allowed Joch into most areas of the site, but not all. Others were frustratingly out of view, including one marked “Producer’s area”. That was all about to change. In early 2014, Dutch investigators busted a longstanding member of the KidClub with his computer still running, allowing them to access the locked network. This led to the arrest of other senior members in Denmark and Sweden. Somewhere within Argos’s reach was the man running the show – a predator who was also producing videos of his own abuse of children and distributing them to a tight group of co-administrators. Seized material showed him sexually abusing Aboriginal children, and there were references to him as “Aussie Dad”. At least seven victims were observed in the footage, and there were links to up to four more. They were as young as 18 months. It was a nightmare scenario for Argos. Somehow NUKE had access to large numbers of children, and every day brought the risk of more kids being harmed. But his face was out of view in all images. They needed to crack his identity. Fast.

Enter Paul Griffiths, Argos’s victim identification manager. Griffiths had amassed an immense knowledge of child pornography from his years fighting its insidious trade with the Greater Manchester Police and Britain’s National Crime Squad. Joining Argos in 2009, he had previously met Det. Insp. Rouse during a multinational investigation into videos of an Australian paedophile raping an eight-year-old girl he had injected with stupefying drugs. To this day, that case is one of the worst Rouse has ever encountered, the little girl’s screams still vivid in his memory.

In May 2014, Griffiths took a call from a colleague in Denmark who alerted him to new photos and videos of the KidClub chief. The abuser’s face remained out of view, but it was the beginning of the end for McCoole. Griffiths, chair of the Interpol Specialist Group on Crimes Against Children, set about trying to find the notorious paedophile. The make, model and serial number of the camera used to record the images were identified.

A freckle on the offender’s ring finger was noted. A fingerprint was even detected on one of the Australian’s printed photos, but did not match any available databases – McCoole did not have a criminal record. But none of those things identified who he was.

One of the few leads to his identity came from an email address that linked NUKE to a fake Facebook profile. The profile had only two friends, both Adelaide schoolgirls unaware they were being watched by a monster. From this, it was assumed he was most likely in Adelaide. “It was a bit thin, really. At that point we didn’t have enough to definitely say he was from South Australia,” Griffiths says.

Then Griffiths noticed a small clue that would prove to be the game changer: NUKE had regularly used an unusual greeting, “Hiyas”. Griffiths searched online for people using the same salutation on the “surface web”, focusing on Adelaide. At first there were thousands of matches.

Griffiths noticed it was mostly women who used the greeting and delved deeper. The first man he found was on a 4WD forum. Griffiths’ eyes widened as he saw similarities between the username and the one on KidClub. The 4WD enthusiast had gone on the forum to discuss lifting the suspension on his VW Amarok. Griffiths conducted an online image search of the username and vehicle model. Bingo. A match. Zooming in on his 55-inch computer screen, Griffiths could read the SA number plate.

The mystery man was signing off his posts “Shannon”. More online searches led Griffiths to a Facebook profile, where he saw a full name for the first time: Shannon McCoole. Listed there was McCoole’s prior work with children at Camp Horizons in the US and in holiday care at an Adelaide primary school. South Australian police, following up on Argos’s 4WD lead, had turned up the same name and phoned Griffiths to share the news. Griffiths got in first, asking: “Is it Shannon McCoole?” The SA checks also found McCoole had worked with children in group homes for Families South Australia. All the horrifying pieces fell into place. That’s how someone gets access to seven pre-school children, thought Griffiths.

It had taken him two weeks to crack the case. But Argos was not going to settle for just an arrest. If they had the chance, they were going to become McCoole. “Assuming control of the network provided an opportunity to identify, target and remove as many of the key administrators as we could,” Rouse says. From their earlier work with the VIP member, they knew about the structure of the KidClub and were perfectly placed to secretly hijack it. The US had led at least one similar operation but that was on a smaller scale, involving a website with about 10,000 customers. This was much bigger, and would be the first time an Australian agency had attempted such a manoeuvre.

ON TUESDAY, JUNE 10, 2014, GRIFFITHS AND Argos detective Libor Joch flew to Adelaide as SA police prepared to raid McCoole. Surveillance teams at first detected no movement inside his home – until McCoole stirred, confirming his presence. A detective knocked and waiting teams of police moved in.

The Argos investigators followed their counterparts from SA’s Sexual Crimes Investigation Branch inside. On the living room table, the laptop was open, turned on and plugged in to an external hard drive. McCoole had snapped shut his laptop. In that instant the whole operation teetered on catastrophe. If his screen was locked, police faced a likely unbreakable wall of encryption. When an officer lifted the screen, it was mercifully still unlocked.

There was more luck. McCoole had not had a chance to log in to the KidClub, but the palm-sized portable hard drive had a complete backup of the website. On a loungeroom shelf was the camera McCoole had used to record his rapes and assaults of kids; on his finger, a small freckle that would be matched to the one seen in the videos. SA police would use all that information to build a rock-solid case against the predator. They would also set about tracking down his victims, the kids whose lives he had irrevocably altered. McCoole was outwardly calm. He asked for a lawyer and declined to speak. For him, it was over.

At court the next day, McCoole appeared before a magistrate on multiple child-sex charges. A huge political storm was brewing about the failings of the child protection system, which would eventually lead to a royal commission. As the media pack gathered outside the court, Griffiths and Joch had a one-on-one with McCoole and walked away with his login details and passwords. The takeover of his identity began then, on a laptop in the Adelaide courthouse.

Young and fashion-conscious, McCoole wore prominently branded clothing. He enjoyed the outdoors, taking camping and fishing trips in the 4WD that would help bring him undone. Physically, he was nothing like the stereotype of a paedophile, but conversely, to the investigators, he was no different from other men they had encountered who lived outwardly ordinary lives. He had risen to the top of the KidClub after German authorities arrested its previous head administrator, a man known as A1, in 2011.

Running a paedophile network in McCoole’s place would be a two-man job. Assisting Joch was his Argos colleague, Det. Snr. Const. Graham Pease. Because of the speed of McCoole’s arrest after he was identified, they had virtually no time to prepare. “It was a cold start, which is the worst possible way you can do that,” Pease says. “Ideally we would have had ten years’ worth of logs to go back and read through. We would have had time to get an idea of how he talks and key stances on particular issues. Unfortunately, all we had was what we read through the visibility of the site. It was a bit of a jump-in-and-hope-for-the-best.”

It would be understating it to say the role was time-consuming and high-pressure. Both men had young families who would have to take a back seat over the next six months. If they were outed as detectives, the operation would be over. McCoole had relationships with sex offenders that went back years. “For us this is a job, for him this was his life,” Pease says.

“The face he put on in the real world was pretend. His real self was the self that was online. It would be nothing for him to spend eight hours at work and then come home and spend five or six hours online every day.

“Unlike us, where we have to have days off, he doesn’t take days off. So that became a real challenge. He’d been in that community for a very long time, he held a very prominent role in that community, he was quite well-known by a lot of people. We just had to have a crack.”

After taking over McCoole’s identity, new sections of the KidClub opened up to the Argos detectives. The Producer’s area, restricted to all but the most trusted members, was a horror show. To enter, members had to provide videos and photos that included visible penetration. Child victims held signs bearing the words “the KidClub” and their abuser’s username.

Argos’s first move was to shut down the Producer’s area so they would not be facilitating child abuse. They then set about identifying members through techniques they have requested be kept confidential so future operations are not compromised. Working in tandem, the two detectives maintained constant contact at all hours of the day and night so they could keep their stories consistent. There were frantic phone calls and text messages to check facts.

It was almost over as soon as it began. The arrest of McCoole was national news. Some of the senior members of the KidClub knew the head administrator was from Adelaide and worked with children. Suspicions were aroused in the network. Pease and Joch, posing as McCoole, managed to convince the doubters the arrest was unrelated.

In interviews it became clear he thrived on the status and power of running the KidClub. He thought he was a brilliant carer; that he could understand children better than his colleagues. He’d also grown brazen. He told detectives that one day at work he had to go to a meeting about the risks of children being sexually abused. In the middle of the meeting he interjected, commenting: “There could be a paedophile right here in this room and you wouldn’t know it.” As a Christmas present, McCoole had sent KidClub administrators videos of him raping children.

ONCE THE ARGOS OPERATION WAS UP AND running, the first target was a man we’ll call 2IC. Based in Europe, he had access to the KidClub’s server, and with it had the power to lock the detectives out if they were busted posing as McCoole.

On arrest day, dozens of police including heavily armed riot squad officers waited outside 2IC’s home. Back in Brisbane it was night, and detectives Joch and Pease were at police headquarters. The plan was for the Queensland officers, posing as McCoole, to engage 2IC online while police quietly entered his home and arrested him at his computer.

Unexpectedly, their target left his house, delaying the raid. It was 4am Brisbane time when he finally returned and turned on his computer. Det. Joch, posing as NUKE, was waiting for him online. Joch had the flu and worked it into conversation with 2IC. As they chatted, police quietly entered the house. They were making their way up the internal stairs when 2IC went for a toilet break. He never made it to the bathroom. A message was relayed back to Joch – their target was in custody and they had full access to his computer.

From then on, with control of the server, the Queensland squad would have full control of the KidClub. No-one could evict them and they could kill it whenever they wanted. Why would you do that? thought Rouse. We want to take down as many as we can. Server control also gave Argos access to private messages between members, yielding more evidence. “From there it was just a matter of working down the list,” Pease says.

Meanwhile, in Europe, a KidClub member called Kerbside was a walking encyclopaedia of child pornography. He also wrote long online lectures about how to avoid detection. “If Paul Griffiths was a bad guy, this guy would be Paul Griffiths,” Pease says. “He had a knowledge of child pornography that would rival anyone in the world.”

Kerbside liked his acolytes to be in awe of his unrivalled child pornography collection and knowledge. You could say anything to him and he would produce an image of it. Once, police were watching when he was challenged to find an image of a child with a fish in the picture.

“Would you like a blonde girl, would you like a red [-headed] girl, would you like a dark girl?” Kerbside fired back. Then image after image appeared of a child with a fish in the picture.

Members who got their facts wrong would be swiftly corrected. Pease says: “Someone would say, ‘This is an image from the Sarah series’ and he would go, ‘No, the third image is not part of the Sarah series’. He just would know, and he was dead right every single time.” Thanks to Argos and its KidClub operation, he was arrested at his computer.

In North America, an offender was chatting to Pease online, believing it was McCoole, when a SWAT team stormed into his home and arrested him at his computer. Pease, informed by email that the offender was in handcuffs, sent a final message just in case it had been a bluff: “I don’t know what you’re doing that you think is more important than talking to me but whatever it is, it isn’t. Get your arse back to the keyboard.”

Other arrests followed in Queensland, Victoria and NSW. Some cases are before the courts and cannot yet be reported as suppression orders apply, but when revealed will make international headlines for the sheer depravity of the offences involved.

Posting child-abuse material online is a criminal offence. After taking over the site, Argos started recording instances where members broke the law. Investigative leads were sent internationally for other jurisdictions to take action. When Argos felt they had taken out as many as they could, they pulled the plug on the site around the end of 2014. The KidClub was obliterated.

LAST MONTH, McCOOLE WAS CONVICTED OF running the KidClub and abusing seven children in his care. He was sentenced to 35 years in jail. But before his sentencing, he sat across a table from Det. Libor Joch, one of the men who had effectively become him to take down his network. Their talk turned to a member of the KidClub who promoted “hurtcore”, a form of child abuse where the offenders derive pleasure from inflicting pain on their victims. McCoole spoke derogatively of the administrator, but Joch told him flatly that, in his mind, there wasn’t any difference to the abuse inflicted by the man sitting opposite him. McCoole took offence.

For the next interview, Argos colleague Graham Pease sat across the table. McCoole had refused to talk to Joch again.

Meanwhile, the trade in child-abuse images continues. Online, arrests are dissected by networks of paedophiles that have not yet been brought down. When McCoole was convicted and news first broke of the Argos operation to take over his identity, child-abuse forums lit up. “Kudos,” reads one post. “I was talking to [NUKE] for the entire time he was taken over and I had no idea.”.