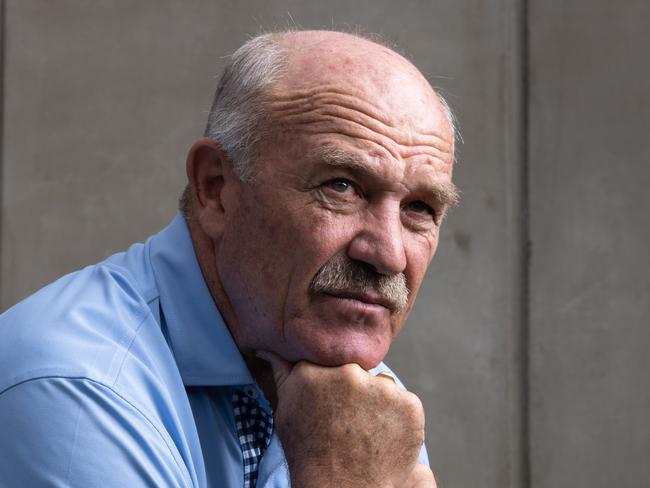

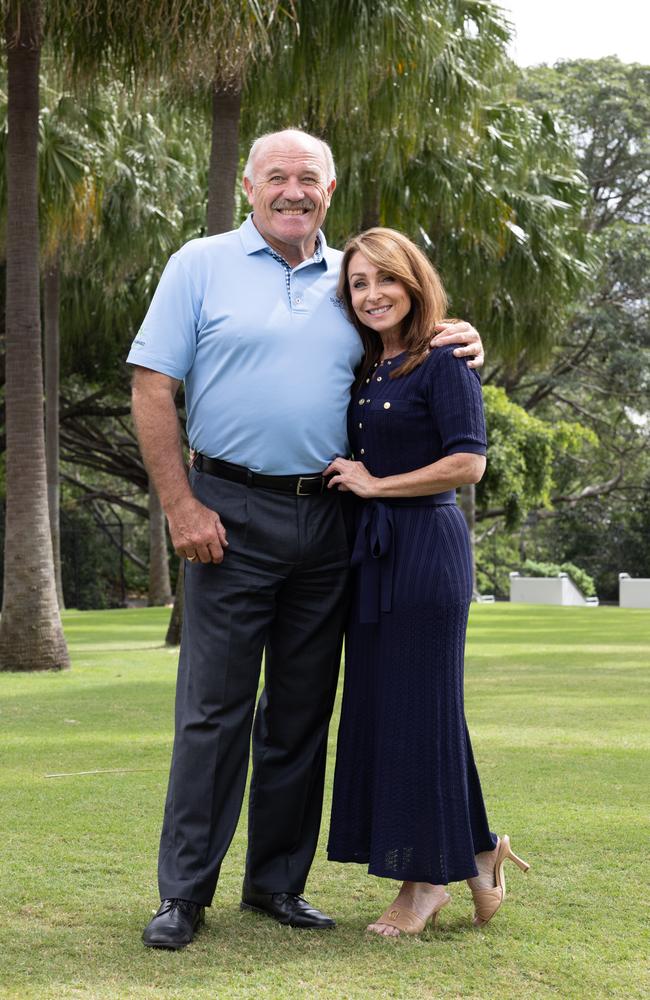

He was a hero in the days when head knocks were simply part of playing footy. Now Wally Lewis and partner Lynda Adams are revealing the impact of the brain disorder, CTE, on his daily life.

Even heroes must have heroes.

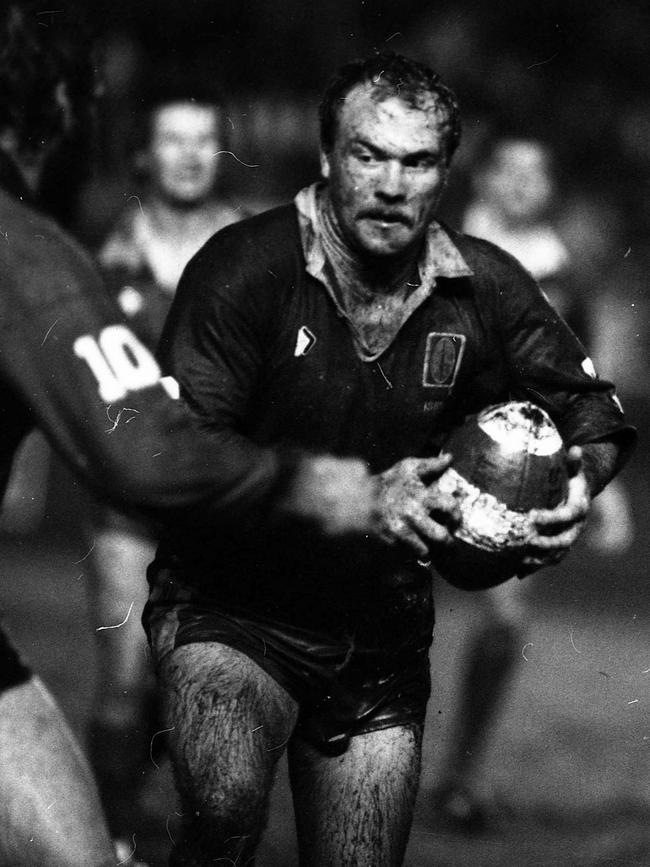

When rugby league icon Wally Lewis was a boy growing up in Brisbane’s Cannon Hill he had one idol who stood above all others – crash-tackling Manly-Warringah backrower Terry Randall.

With enough defensive crunch to uproot an oak tree, “Igor’’ Randall was the sort of player young boys craved to be. Fearless, fearsome and mildly frightening if headed in your direction.

But time moves on and the reverence Lewis once reserved for Randall has shifted beyond rugby league and even sport itself.

While a part of him still cherishes the memory of the man who made the big hits, Lewis now has the deepest admiration for those who try and clean up the damage from the occasional ones that go wrong – not simply for the player on the receiving end but to the ones performing the tackles.

It was regarded as, you know, the price you pay for footy.” – Wally

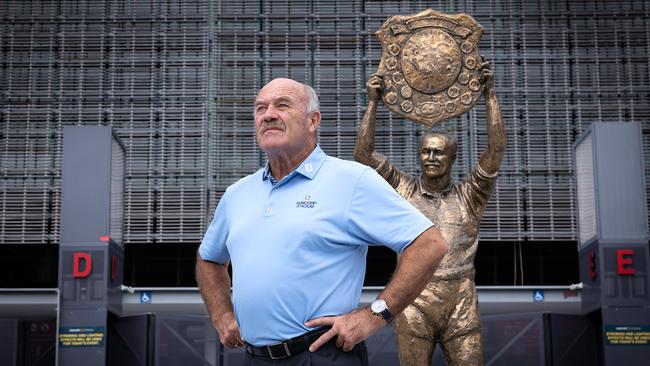

As Lewis and partner Lynda Adams join me in the FOGS’ (Former Origin Greats) boardroom in Castlemaine St, Milton, famous rugby league photos look down on us from all directions as we sit just a punt kick away from the ground (Suncorp Stadium) which was Wally’s private kingdom.

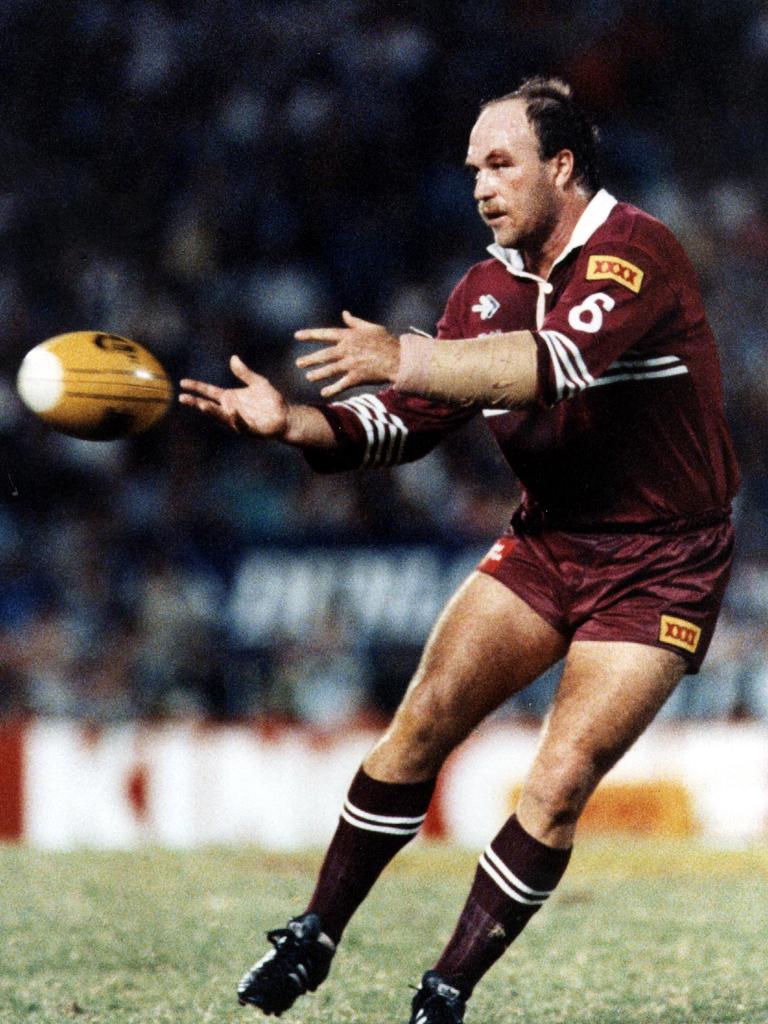

Sitting proudly and prominently on the wall is arguably the greatest treasure of all … the Queensland State of Origin jersey Lewis wore in his legendary farewell match in 1991.

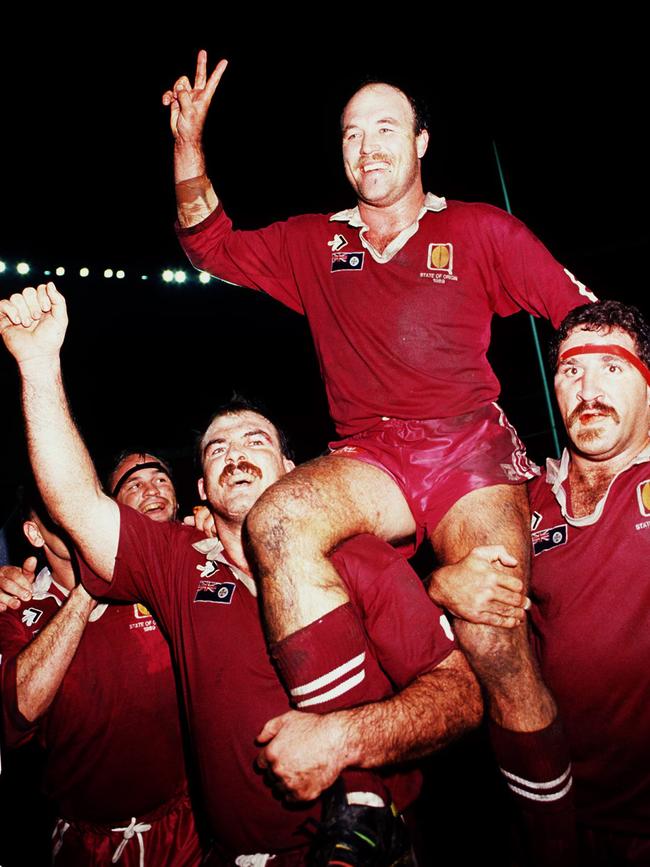

Talk about theatre. The ground announcer informed the crowd of 33,226 10 minutes before the end of the game Lewis’ Origin career was about to end and Queensland, to the delight of the raving masses, squeaked home 14-12.

Lewis gifted the jersey to long-time team manager Dick “Tosser’’ Turner. When Turner died in 2008 Lewis told his widow Jan that if she wanted to put it on his coffin he had no problems with that even though it was one of the most significant pieces of memorabilia in Queensland rugby league history.

But she wanted it to live on so here it hangs as a silent salute to the player who, after several soul-destroying decades when Queensland sporting teams often couldn’t win so much as a chook raffle, lifted the entire self-esteem of the state through Queensland’s early State of Origin dominance against NSW, with Lewis involved from its inception in 1980.

The scent of rugby league is so rich in this room you can almost smell the liniment and it seems slightly inappropriate to ask Lewis if anyone not photographed on the wall could be one of his true heroes.

But the life he led way back when is not the one he leads now.

When I asked Lewis whether medical experts who have saved and realigned his post-football life are his new heroes he initially offers no words. He simply holds out his arms in front of me.

“I guess there’s your answer – have a look at those,’’ he says. The King has goosebumps. And plenty of them.

He’s getting a bit emotional because he knows how much he owes to people like Sydney neurologist Dr Rowena Mobbs who diagnosed him, with 90 per cent certainty, as suffering from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the brain disorder caused by repeated blows to the head, often triggering memory loss, the deterioration of basic cognitive skills and behavioural issues.

And he has always felt deeply indebted to another neurologist, Melbourne neurosurgeon Professor Gavin Fabinyi, who in 2007 cured Lewis’s long-time and deep-seated battle with epilepsy with a brave “last resort’’ operation that required the removal of a chunk of his brain. “He (Fabinyi) is the guy that allowed me to enjoy life again,” Lewis says.

“I had issues for decades. I hid it. I kept it quiet. There were times when (fellow league great) Gene Miles would say that someone said to him that I had the personality of a dead fish.’’

Little did they know Lewis, famous for his lack of fear on the football field, was living with the crippling fear of having a seizure any time, anywhere, in front of people he barely knew.

Before his condition became public after an on-air seizure while reading the news on Channel Nine in 2006, Lewis’ coping mechanism was to try and minimise the fallout of any unexpected meltdown by deliberately keeping his distance from people.

It was a different sort of anonymity than what he craved at the height of his playing days when he was so in demand he changed his phone number in the Brisbane White Pages to W (Wally) Gator.

“I think once you make the decision to see people, you want to see the best, and I was extremely happy with Rowena Mobbs.

“She shed a tear in front of me. I can’t remember what I said but I was basically just telling her of my discomfort and embarrassment, then, at the end of the sentence, she said, ‘Look, I am having a bit of trouble with it’ and she wiped her eye.

“She would hear a dozen declarations like that a day. But she told me people think that the more people you hear the easier it is to process but it doesn’t work that way.’’

Chastening though it was, the diagnosis he revealed last year at least allowed Lewis and Adams to know what they are fighting and, as well as plotting their own life forward, are now crusading for the cause.

The 64 year old, who played more than 400 games of senior football including 31 State of Origin games for Queensland, recently led a delegation of about 20 people to Canberra crusading for more funding for CTE awareness, support and education in May’s federal budget. He is also involved in fundraising for the University of Queensland Brain Institute.

Lewis’s openness about his plight is in contrast to many fellow footballers who suffer in silence.

“It’s not funny but some of the guys who have it come up and start doing this,” he says before looking sneakily over his right then left shoulder as if he is guarding the world’s biggest secret.

Adams adds: “It is preventable but there is no cure. There are certainly things that can be done to assist them with their symptoms … depression, anxiety or sleep disorders.

“They can get treatment which can make their everyday life more enjoyable rather than living in this world of ‘I am alone and what am I going through?’’’

Well, the most simple thing is try not to be furious at myself for my inability.” – Wally

LIVING WITH WALLY

Lewis does not trust his own powers of recall but he does trust his “new best friend’’ – his diary.

“I don’t go anywhere without it,” he says. Each day is colour coded with the events that are “absolutely essential’’ highlighted in bright red. His phone constantly beeps with reminders which are a welcome safety net. Lewis’s reminder system is synchronised with Adams’s phone as yet another back-up.

“The big thing for me is trying not to be furious at myself or my inability when my recollective skills are tested every day,” he says.

“I will say something to Lynda. Then I will say, ‘Have I told you that before?’ She is very good and will say, ‘You have told me a couple of times already’ and I will think arrrgggh.”

Adams accepts one of the essential requirements of supporting Lewis is staying calm and tolerant and advice from an unusual source gave her a key line to cling to.

“I remember listening to this great podcast where this woman said when you are faced with adversity in life, be the air hostess,” she says. “The way she explained it was that if you are flying and you hit turbulence and the air hostess is running around crazily, it is time to panic. But if the air hostess just keeps handing out the peanuts then everyone stays calm.

“It is the short-term memory and the repetitive stuff. Wal might tell me a story and 10 minutes later he will tell me that story again. I just get on with it. There is no point in me highlighting that to him or getting frustrated. My role is to support him as best I can.

“There is nothing I won’t do to support him.

“There are times when I say, ‘Say g’day to the guys at Channel Nine’ and he will say, ‘Am I going there?’

“I did have one lady talk to me about it and she said her husband had been diagnosed with the early onset of it and she was so angry and frustrated at him because he forgets everything she tells him. I said to her I can understand it but it doesn’t help you or him.

“People can’t help their illness.”

HUMOUR

Beneath the draining seriousness of his plight there are also the splashes of humour every grim situation needs.

Adams jokes Lewis can remember intimate details of a match in 1982 yet if she asks him to remember where the ironing board is he can have a sudden brain fade.

“It’s the same with how to use the dishwasher and the washing machine … it’s quite calculated. You have to have a laugh. We say you cannot get too serious about it.

“Sometimes we will talk about something and he will say, ‘Have we just spoken about that?’ and when I say yes, he will say, ‘OK, I am off to work … bye Stephanie.’”

WATCH YOUR HEAD

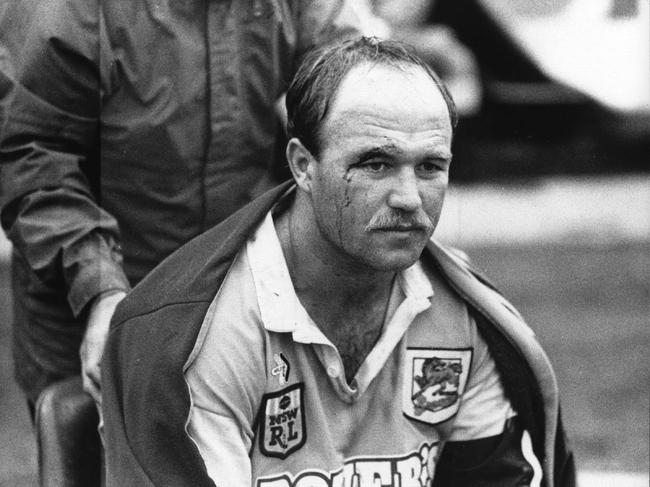

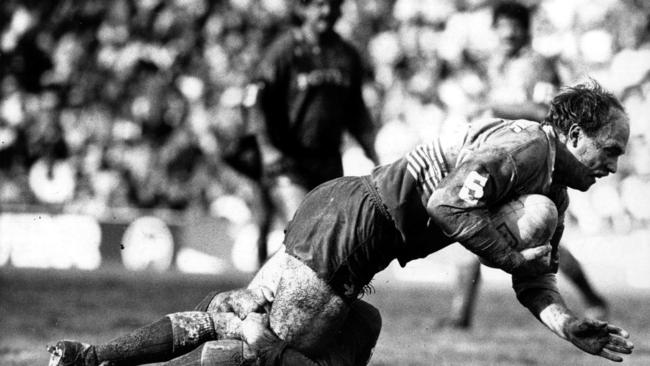

Lewis looks back not in anger but with sober reflection on the toll rugby league took on his life in an era when playing on after a head-knock was seen as a measure of a man’s true fibre.

“It (a head knock) was regarded as the price you pay for footy. I remember I used to get concussed and walk off and my father (Jim) would come up and say, ‘You put your head in the wrong f--king place.’

“He’d say, ‘You put your head behind his legs, not in front.’ We used to do these drills in the back yard.”

Jim Lewis taught his son to tackle at age three, claiming, “If you can’t tackle, you can’t play the game because that is what it is about.”

Wally’s first tackling target was his father’s legs. Then Jim sent his son to judo sessions at age 10 because he wanted to teach Wally that, despite his slim physique, he could find a way to throw bigger men to the ground.

Wally knew from his time as a school liaison officer for Queensland Rugby League there was a fundamental fault with rugby league tackling styles.

He noted 90 per cent of players were right-handed so, when tackling, would lead with their right shoulder. When their opponent was heading to the defender’s left that often meant the tackler’s head would be in front of their opponent’s body.

“And that often meant a knee in the head or the player with the ball would land on the tackler’s head.”

So Wally recited his dad’s creed over and over to willing school children … “You simply must put your head behind the attacker’s body.”

Jim’s standards for Wally’s tackling were stratospherically high.

Jim so enjoyed being part of his son’s journey that occasionally when he returned home from work after dark in winter he would put the car headlights on to supervise a training session in the back yard.

“I remember coming over to him after we had won a State of Origin game and thinking, ‘How well did that go?’ and he would say, ‘I know you scored a try and set up a few others but I noticed you also missed a couple of tackles over the other side.’ I would think, ‘Righto’.

“But in a funny way it was the best thing for me. He would say, ‘Never get carried away.’ His advice was wonderful.

“Sometimes I would challenge him by saying, ‘You occasionally just don’t get the time to get the tackles right’ and I meant it too. That’s what I used to say to players in the State of Origin camps. ‘Please don’t get dirty on yourself if you miss a tackle. It happens.’”

This is the one form of dementia that’s preventable.” – Lynda

SUFFERING IN SILENCE

Lynda Adams knows Wally is not the only former rugby league player suffering and some are facing more acute challenges.

“I am finding a few of the wives contact me because their husbands are in denial and don’t want to know about it,” she says.

“The wives are the ones witnessing their behavioural changes and they want to help.

“One particular lady – this was just heartbreaking – said her husband does not want to see anybody. He has paranoia, which is another symptom. He keeps the curtains closed in the house and won’t go outside.

“They had to call the police because he was chasing them around the house. The thing is he can get help from doctors and medications which could really make a difference and help that anxiety and anger.”

Wally is extremely saddened by the news because the man is a former teammate of his who had a vastly different persona as a player.

“He was never an aggressive player to the point where you wouldn’t want to be involved in a brawl and expect him to help out because he never lifted a finger in that sort of way. He was a lovely bloke who was always in a good mood. It’s very sad.”

SLEEP APNOEA

As if he needed another challenge Lewis has been diagnosed with sleep apnoea. At one point in an overnight sleeping test he stopped breathing for 62 seconds.

“I couldn’t believe it because I can’t hold my breath for 62 seconds,” he says. “I even tried to do it in front of the doctor and got to about 50 seconds.”

Lewis tried the CPAP machines – which comedian Kitty Flanagan jokes, with their tight fitting masks and background hum, are so unromantic in bed that partners of people who wear them should be granted automatic divorce – (“No one signs up for that!”).

But Adams, a former dental nurse, saved the day by organising a special mouthguard to be built which greatly improved his breathing.

The challenges go on. But so does the King. He’s wounded but he still looks fit and strong and has retained the slightly mischievous smile of a man who knows more than he is letting on.

“I don’t blame the game,” he says. “Rugby league gave me a lot of great things and I am very thankful for that. I don’t regret a thing.”

What is CTE?

By Tonya Turner

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a brain disease caused by long-term exposure to repetitive head injuries.

Each year neuropathologist Michael Buckland, head of neuropathology at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre, conducts around 200 autopsies on brains looking for CTE and other diseases.

“There are currently no tests that can diagnose CTE during life. At the heart of our goals is the development of clinical tests that can diagnose CTE in people while they are living,” Buckland says.

As director of the Australian Sports Brain Bank, which found the first cases of CTE in ex-players of AFL, rugby league and rugby union, Buckland says research in the field is in its early stages and brain donations are vital to understanding more about the debilitating illness.

CTE was first recognised in boxers in the 1920s, when it was referred to as “punch drunk syndrome” or dementia pugilistica. But it wasn’t until the new millennium, when CTE was found in American football players that it started to gain worldwide attention.

Queensland Brain Institute neuroscientist Fatima Nasrallah says while CTE is most commonly associated with high-impact sports, it also occurs elsewhere. “You see it in military personnel, in cases of domestic violence and in those who engage in high risk activities. We need to raise awareness that the brain is just like any other organ. If it breaks, it needs time to heal,” she says.

Repetitive hits or forces to the head including both concussions with symptoms and sub-concussions with no symptoms can lead to CTE. These injuries can cause a build-up of tau protein that over time can lead to cell death and brain shrinkage. It is currently not known how many injuries or how many years it takes for this to happen.

Genetics and lifestyle choices are also understood to be factors, as studies have found not everyone with a history of repeated brain trauma goes on to develop the disease.

While symptoms of CTE cross over with other diseases, they may include memory loss, attention difficulties, explosivity, impulse control problems, paranoia, depression, tremors, slurred speech, suicidal ideation and more. Symptoms usually start in people in their 40s but can appear in some in their 20s.

There is currently no cure, however treatment is available to help people experiencing symptoms and to slow progression.

Given CTE is the only preventable form of dementia, Maree McCabe, CEO of Dementia Australia says much work needs to be done to educate people about the risks of repetitive brain injuries and CTE.

“It is so important we get the message out for people to protect their brain and get the message out for children,” McCabe says.

Although there are concerns in the scientific and medical community about diagnosing “probable CTE” while people are alive, there are clinicians who believe it can help.

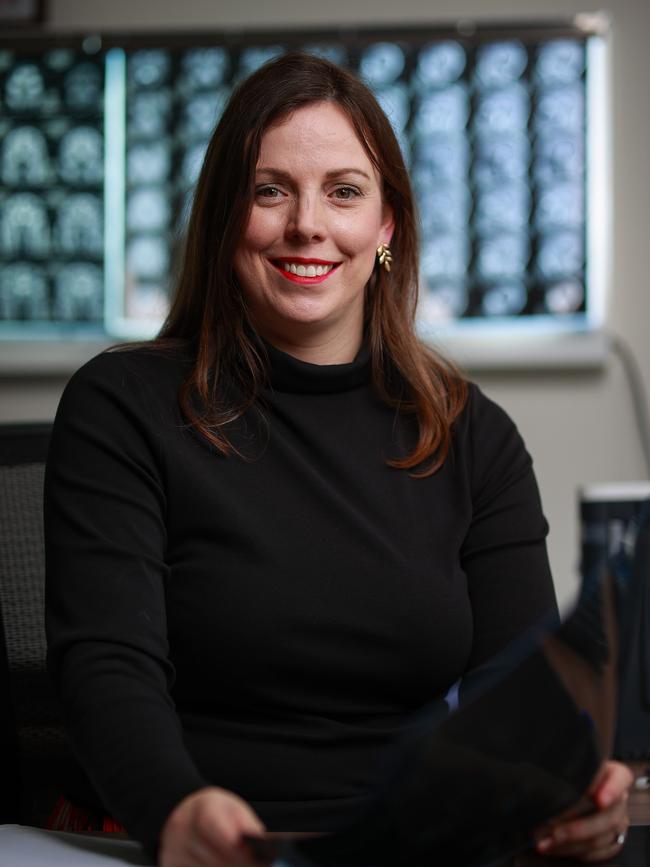

Neurologist Rowena Mobbs of Sydney’s Harbour Neurology Group says she uses a number of tests to form a “picture” of suspected CTE in her patients. “Our approach as cognitive specialists is to say we can exclude many other subtypes of dementia, and in particular cases, if it looks highly likely that it is CTE … we approach CTE like we would any other subtype of dementia in that we provide environmental measures and advice around a person’s functioning day-to-day, we provide support and validation for them and their families, and importantly we provide symptom management specifically for memory loss and mood stabilising medications,” Mobbs says.

In September, a Senate inquiry into concussions and repeated head trauma in contact sports made 13 recommendations to improve the identification and prevention of these brain injuries. These included national sporting organisations exploring rule changes to protect adults and children, urgently developing a national sports injury database, funding more research, encouraging Australians to donate their brains, improving community awareness and education, developing return to play protocols and more.

The Brain Foundation’s director of operations Carl Cincinnato says it’s time our sporting culture changed.

“Our culture of sucking it up and getting back on the pitch is misguided,” he says. “As someone who plays competitive sports, we don’t want to rob the game of all its joy. It’s not about making sports boring or taking away the physical contest. It’s about playing the game in a more informed way that acknowledges the risks.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Unexpected way morning TV icon found love at age 56

This is the sliding doors moment that Gold Logie nominee and TV presenter Lisa Millar found the love of her life.

I had a marriage breakdown – this is what it taught me

An Australian author has opened up about her marriage breakdown and what she learnt from the heartbreak.