The definitive account of the Lindt Cafe siege

They were brought together by a madman. They faced 16 hours of terror together. They were traumatised, in shock, and expecting to die. But they found strength in each other. They are the Lindt cafe survivors who proved to be Unbreakable.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

They were brought together by a madman. They faced 16 hours of terror together. They were traumatised, in shock, and expecting to die.

But they found strength in each other. They are the Lindt cafe survivors who proved to be Unbreakable.

In this special report, we bring together the definitive report of what happened on that day, based on their own testimonies.

If you are on a desktop, click here for an interactive, user-friendly version of this article.

Harriette Denny

LINDT Cafe barista Harriette Denny was 14 weeks pregnant and still hadn’t told her parents.

Worse still, thanks to the events unfolding around her in the cafe, the 30-year-old was now convinced she might be dead by the time they found out.

This psychopath holding the gun, who said he had a bomb in his backpack, had been talking all day about killing Ms Denny and the rest of the hostages, but never himself.

And the longer the night went on, the more Ms Denny was convincing herself that he was going to follow through with the threat. “I’m never going to meet my baby,” she thought to herself. That thought alone almost killed her there and then.

Ms Denny had been a barista at the cafe for about 18 months after moving down from Mooloolaba via a lengthy stint at restaurant on The Sunshine Coast.

She arrived at work on December 15, 2014, at 6.30am and spent 30 minutes before her shift started with her manager, Tori Johnson.

The barista made him a coffee and they talked about their weekends.

Most of the regulars came in during the pre 8.30am rush.

About 9am she noticed a man sitting at one of the tables.

He looked to be in his 40s, had brown skin and was wearing a white long-sleeved t-shirt with no collar.

Ms Denny made an English breakfast tea and one of the waitresses took it to him.

She took a drink to another table and walked past the man on her way back to her work station. He smiled at Ms Denny and she smiled back.

The next time she walked past him he stopped her and said “I need to go to the toilet, can you watch my bag?”.

Ms Denny thought the request was weird. She looked at the bag and then at him.

“He was smiling, always smiling and appeared very friendly,” she would later tell police.

Ms Denny agreed and walked back to the coffee bar.

She continued to watch the man, but he didn’t move to the toilet.

He then got up and greeted another man, who appeared to Ms Denny to be a lawyer - many of the customers were given the cafe’s proximity to the NSW Supreme Court and the countless legal offices in and around Phillip St.

Another waitress, Fiona Ma, walked past the man and he made the same request to her.

When the man returned to the table from the apparent trip to the bathroom, Tori sat down with him.

The man still had a big smile on his face. He had a piece of paper and was leaning over the table talking to Tori.

“I didn’t get the impression he was complaining about anything,” she later told police.

Ms Denny went back to the kitchen to eat some fruit toast when fellow cafe staff member, Jarrod Morton-Hoffman came in with a strange look on his face.

“I don’t want to alarm you, but Tori has said to me to stay calm and we are in lockdown,” Mr Morton-Hoffman told Ms Denny.

“Oh yeah?” she replied, thinking there must have been something happening outside the store on Martin Place.

Fellow barista Joel Herat came up to Ms Denny and said “are we going to be ok?”.

“Of course we are,” Ms Denny said, before giving him a hug.

Ms Denny walked out of the kitchen and saw Tori still at the table with the man with the backpack.

Tori’s face was red.

“His face gets red when he is stressed,” Ms Denny thought.

Tori was talking on his mobile phone and the backpack man was still leaning in, nodding his head, and smiling.

Ms Denny saw two police officers come and look in the main entrance to the cafe before they leaving without looking concerned

The doors were closed, locked and featured a “closed” sign that had been drawn up by Mr Morton Hoffman and Mr Herat.

There must be something serious happening on Martin Place, Ms Denny thought to herself.

One of her colleagues walked to the retail section of the store, so Ms Denny followed him.

She then saw the backpack man standing in front of the barista counter, brandishing a gun.

The only guns Ms Denny had seen were in the movies, but this one was very real.

The gun was long with a dark metal barrel and the part where you put the bullets was gold coloured. He was holding it on an angle with the barrel pointing to the ceiling.

The man ordered everyone to go to the back seating of the cafe that faces out to Martin Place.

“You are going to be held captive until I get to onto ABC National,” he told the group of hostages. “If my demands are met, I will let you go.”

Ms Denny started crying.

Noticing this, the gunman looked at her and said “don’t worry about it, you will be ok, you will get out of this”.

He then demanded two of the female hostages, barristers Julie Taylor and Katrina Dawson, to stand at the main door with their hands up holding a flag against the window.

The flag was black with white writing that looked to Ms Denny to be a Middle Eastern language.

It was a small flag and one person could have held it, Ms Denny thought.

Ms Denny was standing near the barista bench when the gunman told her to go to the window and put her hands on the window.

She wiped the tears from her eyes and obeyed the command.

Looking outside, she could see a “whole heap” of people from the Channel 7 building, opposite the cafe, filming what was unfolding.

She heard his voice again from behind.

“Close your eyes,” the gunman said.

“He’s going to shoot us against the windows,” Ms Denny thought, silently freaking out.

“He was smiling, always smiling and appeared very friendly”

The shot never came and she heard him take something out of his backpack. When she next saw him, the gunman was wearing a bandana that had a white symbol on it. It was like the writing on the flag.

He was also wearing a black vest with the same writing.

Despite his menacing presence, the gunman would let people go to the toilet and get water, continually reminding them “I’m a nice guy. It want peace. If you get tired, let me know”.

He made them keep their eyes closed for most of the morning. When someone opened their eyes he said “I will shoot you”.

He repeatedly reminded the hostages: “If you try to escape, I will kill the people who are left and you will be charged with their murder”.

“You will be responsible for their deaths and you will be prosecuted,” he said.

There were Christmas carols playing in the cafe and it annoyed the gunman. He asked one cafe staffer to turn it off. When the staffer couldn’t figure out how, he sent Ms Denny.

When she switched off the iPod in the office and returned, the gunman said she had gotten a “credit” for turning off the music.

He then went on to give a monologue, explaining that people would get credits for behaving but if you were bad he would take credits away. He would remember the credits when he released them, he said.

About lunchtime, the gunman asked Tori about sandwiches and got one of the waitresses to hand them out.

Ms Denny sat down in front of the till and had a chicken sandwich placed in front of her.

She wasn’t hungry but thought “I don’t know how long I’m going to be here for. I need to be smart about this. I’m pregnant and I need to eat. I don’t know when the next chance will be”.

The man next to Ms Denny couldn’t eat.

The gunman kept rotating the people who were holding the flag in the window.

There was one man who kept getting caught opening his eyes but Ms Denny couldn’t see who it was.

“Why aren’t you listening to me,” she heard the gunman tell the rule-breaker. “I’m going to shoot you because you’re not listening to me.”

It was at this point that the gunman was getting hostages to call media outlets to tell them what his demands were.

He wanted an IS flag, to put a message out to his brothers not to detonate bombs at Circular Quay and George St, and to have a conversation with Prime Minister Tony Abbott on TV or radio.

He would release hostages if the demands were met.

Ms Denny’s phone was upstairs in her locker.

The 30-year-old got emotional while eating her sandwich. She was thinking about a minor fight she had with her partner, Jorge Bonora, that morning and the fact that she hadn’t told her parents about the pregnancy.

Ms Denny put her hand up and asked for a toilet break. She was escorted with her eyes shut by waitress Fiona Ma. The man said they couldn’t open their eyes until they got to the toilets.

Ms Denny grabbed her mobile on the way. She took it to a toilet stall and called Mr Bobora.

“I’m in the building; I’m hostage,” she told him through tears.

He was crying too and they said they loved each other before Ms Denny said she had to go because she was taking too long.

Ms Denny sent a text to her family, in which said she was a hostage and that she loved them.

Looking at Ms Ma through tears, Ms Denny said: “I’m sorry I’m so emotional, maybe it’s because I’m pregnant”.

When she got back, the gunman had rearranged the tables like a barricade.

Ms Denny looked at a male hostage who appeared to be in his 80s. He kept looking at Ms Denny and looked to her like he was planning an escape.

She averted her gaze elsewhere for a while but was drawn back when she suddenly saw a reflection at the front door of the cafe.

The guy in the white shirt was stuck in a partition, which led to the front door.

He was stuck there for a second before he broke free and ran out the front door.

He wasn’t far behind the old man whose back Ms Denny could also see running out the door.

Ms Denny looked at Paolo Vassalo, her fellow hostage and the cafe’s backhouse supervisor.

Mr Vassalo looked at the gunman and took off, running towards the kitchen.

Ms Denny heard a glass smash and the remaining hostages threw themselves to the ground.

She laid there, frozen with her hands on her ears.

“He’s going to shoot someone, just like he promised,” Ms Denny thought.

Eventually, Ms Denny looked at one of the “Indian guys” being held hostage. She didn’t know who he was but he shook his head while looking at her.

Ms Denny took this as a sign that he was angry with Mr Vassalo for running, putting their lives in danger.

He didn’t shoot anyone, but the gunman yelled “what’s that? Is that the police here?”.

The gunman got the hostages up and dragged them to a table to cover him like a human shield.

They had to convince him that the sound was someone escaping and not the police.

“No please it’s not our fault they ran away,” they pleaded with the gunman. “Don’t punish us for their mistakes.”

Later, Ms Denny was doing a mental headcount when she noticed barista April Bae and waitress Elly Chen hiding under a table.

Ms Denny looked away so as not to draw attention to them.

She kept thinking of escape plans, but the gunman kept saying “If another person leaves, I am going to shoot one of you”.

“He’s probably serious and I don’t want to get anyone killed if I run,” she thought.

“If my demands are met, I will let you go”

Around this time, the gunman asked a hostage to take off their apron, which he hung covering a window above a table. The gunman sat behind so as not to be shot by a sniper.

Ms Denny went to the bathroom again and contacted Jorge who asked “what kind of gun does he have?”. Ms Denny replied “I don’t know”.

When she got back Ms Chen and Ms Bae were gone from under the table. The bolt on the side door where they were was pushed down.

“They escaped,” Ms Denny thought.

The hostages continued trying to call media outlets to have the gunman’s demands broadcast. When they were unsuccessful, they began to lose hope.

When Tori went to the bathroom, the gunman told the two staffers escorting him “if he doesn’t come back, I’m going to shoot one of you”.

Tori returned and Ms Denny was relieved.

“I knew he wouldn’t put our lives in danger,” she thought.

Later, Ms Denny was sitting facing the side door and signalled to Mr Morton Hoffman with her head and eyes towards some sandwiches on the table.

The gunman pointed his gun at Ms Denny’s face and said “What are you doing? Are you going to escape?”.

It became dark outside and the gunman demanded the lights be turned off in the cafe. They sat in relative darkness, still able to see each other.

The gunman was sitting at tables one and two, and only moved with someone in front of him with his gun held to the head or backs.

He was becoming more paranoid. The sound of the ice machine made him jumpy and he demanded the street lights outside be turned off.

Ms Denny was receiving text messages from police negotiators, which she read on bathroom trips.

As the night continued, the gunman let the older women ring their families.

Marcia Mikhael vomited into a bag and continued crying.

“I knew he wouldn’t put our lives in danger”

We might not be getting out alive,” Ms Denny thought.

Katrina Dawson rang her husband. Selina Win Pe rang her mother and was angry about how the police were handling the siege.

The gunman asked Tori who he wanted to ring. After the call to his parents, Ms Denny heard Tori sobbing inconsolably. She wanted to hug him, but didn’t want to move without permission.

“If he’s letting people call their families, this could be the end,” Ms Denny thought.

He might be about to start shooting people, she thought.

Ms Denny went to bathroom and sent a text to her family: “Losing hope, very scared, I love you all”.

At 1.30am, Ms Denny fell asleep. She woke up to see the gunman holding the rifle to Ms Win Pe’s head.

“This is the time to run,” she thought.

She could see Mr Morton-Hoffman moving his hand to the top of one of the cafe’s doors.

This was it.

Ms Denny whispered to Mr Herat “move your legs”, to ensure they both had a clear path to run.

Mr Morton-Hoffman was looking at Ms Denny. She was looking at Mr Herat and the Indian guy. They were all looking at each other. And Ms Denny had an image in her head of the waitress Fiona with a gun to her head.

The next second Mr Morton-Hoffman opened the door and knocked a glass of water, which smashed on the floor.

“F**k it,” Ms Denny thought and ran for the door.

She got out the door and heard a gunshot. She ducked instinctively.

Mr Morton-Hoffman hit the button, the doors open and they sprinted to the police.

In the commotion, she didn’t realise Ms Taylor and the Indian guy, whose name she still didn’t know, were running after her.

Police took Ms Denny to a building, but she was too dazed to take account of where she was.

She heard several bangs and was immediately hysterical. The hostages were being slaughtered, she thought.

“Don’t worry, it’s police making the noise,” one of the police officers reassured her.

She looked out the window and could see flashes of light and heard more loud bangs.

The paramedics took Ms Denny to Royal North Shore Hospital to have her baby checked.

The 30-year-old used her apron as a blanket to keep warm.

Julie Taylor

“This is an Islamic State attack”

IT WAS a routine that barristers Julie Taylor and Katrina Dawson shared most days: car-pool into work on Phillip St and have coffee and toast at the Lindt Cafe on Martin Place.

At 7.45am on December 15, 2014, the two women exchanged texts to arrange the lift and Ms Dawson picked up Ms Taylor in her silver Subaru Forester at 8.15am for the the half hour trip into the city.

After parking on Hospital Rd, both women went to their respective chambers and after discussing coffee plans, Ms Taylor said she would call Ms Dawson when she finished a brief matter in court.

The court matter took longer than expected, so Ms Dawson said she would have coffee with another barrister, Stefan Balafoutis, and would meet Ms Taylor at the cafe.

“Get me a weak coffee,” Ms Taylor texted back, assuming Ms Dawson would have already ordered the toast.

Given she was 18 weeks pregnant, Ms Taylor was wearing a black Angel Maternity dress, under a charcoal grey suit jacket plus Max Mara shoes with black bows on them.

When she arrived at the cafe 20 minutes later, she noticed Katrina was wearing a black pant suit, with a blue and silver zig zagged Carla Zampatti top, and had her black Louis Vuitton handbag.

Ms Taylor joined them at the table.

They finished up, paid the bill and were about to leave when they became aware of a man standing in an alcove near the barista.

The man was speaking moderately loudly, which drew Ms Taylor’s attention.

It took her a second to register what he was actually saying.

“Australia is under attack and by Islamic State and Australia has gone to war,” she heard the man say, but missed who he said Australia had gone to war with.

“This is an Islamic State attack,” the man said. “There is a bomb in the cafe and two other bombs in the city, one at Circular Quay and one on George St.

He wanted a live feed to ABC to tell his brothers not to detonate the bombs and that he wanted to get Prime Minister Tony Abbott on the radio.

The man appeared to have a black sweater draped over his arm and was holding a double barrel gun.

“It looks really old,” Ms Taylor thought, processing the moment. “Like it’s come out of the ark.”

The gunman began ushering people from the from the furthest side of the cafe towards the windows facing Martin Place.

The gunman told Ms Taylor and Ms Dawson to go to the door.

He said something else that Ms Taylor couldn’t understand because of his accent, but it sounded like he was prepared to let the two women go.

Ms Dawson pointed to Mr Balafoutis and said “Can he come with us?”.

When the gunman said “why, are you all together?”, Ms Dawson replied “Yes, he’s our friend”.

But when they got to the door, it appeared the gunman had changed his mind and directed the trio to stand at locations in the window facing outwards.

As she stood at the window, Ms Taylor could see a woman trying to get in through the now locked doors and police trying to herd people away from the cafe.

The gunman ordered two people to stand up and hold a black flag in the window.

As the hostage taker was arranging people, Mr Balafoutis looked to Ms Taylor and said “I think we should go”.

Ms Taylor looked at the door, which was only a metre and a half away and said “No, I don’t think we should go”.

“If we run, he might shoot everyone else,” she thought.

Soon after, Ms Taylor started to wonder if that was the right decision.

With the gunman distracted by people on the other side of the cafe, she said to Mr Balafoutis: “Stefan, do you think we should go?”.

He didn’t answer.

Her train of thought was broken when the gunman announced: “For every person who tries to escape, I will shoot one person. Does everybody understand?”.

About this time the gunman demanded all the hostages close their eyes and threatened to shoot anyone who didn’t comply. Ms Taylor kept her’s open, knowing he couldn’t see her.

The man continued issuing demands about talking to Mr Abbott and moved the flag to the westernmost window.

He also started getting concerned that people, who had their hands up on the windows, were getting tired.

The gunman told them they could put their arms down for a period but soon after demanded they be raised after ten minutes, then later down again.

One of the waitresses was ordered to deliver water and food to the hostages.

People got moved around. At one stage, someone put their hand on Ms Taylor’s shoulder and positioned her further back along the wall along Phillip St.

There may have been another person between Ms Taylor and Ms Dawson but she couldn’t tell how many. And she dared not look.

Ms Taylor was still standing against the Phillip St window when she heard the gunman demanding hostages to call media so he could talk to Mr Abbott, and also to 000.

One of the hostages, Jarrod Morton-Hoffman, received a call from a return call from a police negotiator and passed on a message from the officer.

“He says is anyone here that is pregnant,” Mr Morton Hoffman said, relaying the message.

Ms Taylor stayed silent.

She had hidden her pregnancy until that point and had done her jacket up to conceal it for as long as possible.

Soon after, Mr Morton-Hoffman was ordered to give the flag to Ms Taylor to hold in the window.

As they were walking to the window she said very quietly to the young hostage “I’m 18 weeks pregnant”.

“I’m so sorry, I’m so sorry,” he said. “Take your shoes off before you get up.”

The gunman broke the moment when the announced “the person holding the flag up can have their eyes open and the rest must have their eyes shut”.

While she was holding the flag, Ms Taylor heard the gunman have an altercation with someone near the counter where he threatened to shoot them if they didn’t close their eyes.

Ms Taylor didn’t turn around to look who he was yelling at.

Ms Taylor was still at the window when the gunman started getting paranoid that police were going to come in.

“What can you see?” He demanded to know.

“Brown umbrellas,” Ms Taylor replied.

When he asked “What about Channel 7?”, Ms Taylor lied and said she couldn’t see anyone despite being able to see a cameraman.

“Can you see police?” he continued.

Again, Ms Taylor said “no” despite being able to see an officer and the police line at Deutsche Bank, which had both been there for some time.

The woman next to Ms Taylor, Selina Win Pe, became very ill and wasn’t coping. She laid down at Ms Taylor’s feet, groaning and rolling.

“I might be pregnant,” she told Ms Taylor. “But I’m not sure.”

Hours later, Ms Taylor had her eyes shut but was roused to open them when she heard the cafe’s doors open.

The gunman panicked and became very tense.

He grabbed the cafe manager, Tori Johnson, put the gun to his head, and threatened to shoot him before moving him to the centre of the room.

The commotion gave Ms Taylor a fright and she dove to the floor. All the hostages did too.

The gunman lined six or seven hostages up and motioned to shoot them while ranting “stay back police, I’ll shoot everyone”.

Mr Morton-Hoffman and the cafe manager talked the gunman out of his paranoia and told him it was hostages escaping and not the police.

Ms Taylor knew it must have been Mr Balafoutis who escaped because he was standing near the door that was opened.

“From now on we have a deal. I will shoot someone for every person who escapes,” the gunman said.

After calming the hostage-taker following another set of escapes, Ms Taylor was ordered to stand at a different window.

The gunman approached her and asked “what’s your name?”.

Ms Taylor replied: “Julie”.

He ordered her to call SBS and when she couldn’t get through she tried Channel 9.

Ms Taylor was put in contact with journalist Mark Burrows. She told the reporter of the gunman’s demands and his claims of the bombs.

Mr Burrows offered to pass a message to Ms Taylor’s family, asked about the number of hostages and if the gunman put the bomb at Circular Quay himself.

“No I didn’t, but I know exactly where it is,” the gunman said who added that he didn’t know where the George St bomb was.

There were other questions that Ms Taylor couldn’t answer because the gunman was listening.

After the call, the gunman asked Ms Taylor “What do you do?, and she replied “I am a lawyer”.

“For a lawyer you are not very persuasive,” he said. “I mean, you speak very nicely, but you do not really persuade them.”

He motioned to the rest of the hostages and said “does anyone else want to have a go?”, referring to his demand to speak to Mr Abbott.

Another hostage, Marcia Mikhel, was given an opportunity on the phone and told the person on the other end “what the f*** is Tony Abbott doing? One stupid flag, this man’s request is very simple”.

Listening to the call, the gunman said “See, Marcia was very persuasive”.

After another stint in the window with the flag, the gunman told Ms Taylor he wanted her to make a video listing his demands to be uploaded to the internet.

“You haven’t really done anything to help since you made those phone calls,” he said. “I want you to make the video but be more persuasive.”

“See, Marcia was very persuasive”

After failing to upload the videos to Facebook, the hostages managed to upload it to Youtube and Ms Taylor posted a link on her Facebook account.

By 8pm the gunman knew Ms Taylor was pregnant and used her as a human shield with Ms Win Pe. If Ms Taylor went to the bathroom, he would make her sit by his side when she returned.

As the night progressed, he took Ms Taylor around and pushed the gun in her back while pulling the back of her jacket tight so he could direct her where to go.

“He’s getting desperate,” Ms Taylor thought.

She could hear him breathing heavily and he was darting around the cafe with her.

During one of about six toilet visits, waitress Fiona Ma told Ms Taylor “The fire exit door is unlocked. If anything happens, that door is open”.

Ms Taylor had seen Ms Ma move chairs away from the fire exit earlier in the night.

Later in the evening the gunman continued to plot how to get his message to the public and said “maybe I will release one person as a sign of good faith but that person needs to go and tell everyone the truth” before adding that it should be someone who’s pregnant.

Ms Dawson said “Julie is pregnant, she knows lots of lawyers, she should go”.

“You didn’t help,” the gunman told Ms Taylor.

She replied “I put it on Facebook”, referring to the videos.

She checked Facebook and the videos had gone that she linked to earlier and they appeared to have been taken down from Youtube.

After trying to find the videos to repost, the deal appeared to fall through.

Ms Taylor was still trying to create a new Youtube account when the gunman repositioned three hostages - Mr Morton-Hoffman at the fire exit door and two others to the kitchen door.

Ms Dawson looked at Ms Taylor with a horrified look on her face.

Ms Mikhael said “he’s going to shoot someone”.

“He’s setting something up to kill someone,” Ms Taylor thought.

The silence was broken by what sounded to Ms Taylor like Mr Morton-Hoffman knocking a glass on the floor.

At the same time, Ms Taylor saw Mr Morton Hoffman run out the door.

“I was sitting on the bench and moved at lightning speed and ran out the door as well, with my arm over my head,” Ms Taylor would later tell police.

“Katrina will be doing the same thing,” she thought as she ran towards the door.

“As I was at the door, I heard a gunshot and glass shattered right next to my head as I was running out the door,” Ms Taylor later told police.

She slipped on the marble floor because, by that stage, she had ditched her shoes and was running in stockings.

“I ran down the stairs to Martin Place into (the) arms of police,” she told police. “I was the last person out.”

Ms Taylor was taken for treatment and was later subjected to two rounds of crushing news.

The first was that Ms Dawson was not behind her during her escape.

Worse, she would soon learn that her friend had been killed in the volley of bullets fired in the cafe when police moved in and took out the gunman.

John O’Brien

At 83-years-old, John O’Brien didn’t know if he could do it without being shot and killed.

Mr O’Brien had been sitting on the same chair for hours, slowly edging towards a door of the Lindt Cafe. If he could get to the door without being noticed he might be able to escape into the protective throng of police officers waiting outside.

But if his ageing body failed him, the deranged terrorist who had been holding him and others hostage would shoot him dead.

About 3.30pm he spoke to a fellow hostage he had come to know during the course of the siege as Stefan the lawyer.

The pair hadn’t met until today, and their brief connection was borne out of a shared will to survive.

“I’m going to make a break for it,” Mr O’Brien told the lawyer, who had his hands pressed against the glass.

“I’m going to come too,” Stefan replied, without hesitation.

The only problem was that Mr O’Brien had to stealth his ageing body through a partition without the gunman noticing what he was doing.

Then there was the question of the green button, which on any other day would open the doors.

If the button didn’t work, he was a sitting duck for an unhinged lunatic armed with a shotgun.

He started to move...

It had been a longstanding routine that had brought Mr O’Brien into the cafe that morning.

He had entered the cafe about 10.10am following a doctor’s appointment at Sydney Hospital on Macquarie St.

It was a regular doctor’s appointment, and after every one, Mr O’Brien would follow it up with a visit to the Lindt Cafe, which was a downhill walk through Martin Place.

A self confessed creature of habit, Mr O’Brien’s penchant for routine even extended to his order at the cafe: toast and coffee. Every time.

On this day, December 15, 2014, he sat at the same seat in the cafe as he did the last time he was there and a staff member brought him his order.

Mr O’Brien thought to himself that the cafe seemed quiet when a man walked into the cafe who was characteristic enough to grab his attention.

The man had a full black beard, a high pointed forehead and stood about six foot three inches by Mr O’Brien’s estimate.

The t-shirt the man was wearing featured Islamic writing on the back as did a bandana. The backpack the man was carrying had a noticeable bulge in it, making Mr O’Brien think there must be something inside.

Mr O’Brien also saw that the man was carrying a gun by his side.

Still with a mouthful of toast, Mr O’Brien watched as the man with the gun approached the manager of the cafe and told him to lock the doors.

It dawned on Mr O’Brien that this wasn’t a good situation and he wanted to get out of the cafe immediately, but he knew it was too late.

He did a quick count and figured there was about 18 other people in the cafe.

Within minutes, the gunman had the hostages lined up against the window.

The gunman said “the old man can sit down”, referring to Mr O’Brien.

Mr O’Brien sat down on a chair near the front door and made sure he was as close to the exit as he could get.

He noticed there was a partition near the door with a gap that the front door to the cafe could be seen through.

Mr O’Brien then took note of the green button next to the door.

At 1pm, while he was being led to the bathroom by a girl who worked at the cafe named Fiona, he asked her if the green button worked. Fiona said she didn’t know.

He asked her two more times and got the same answer.

As the tension rose in the cafe, Mr O’Brien got the feeling that if the crazed hostage taker didn’t get what he wanted that he was going to shoot everyone.

The way the gunman was behaving was unpredictable and the things he was saying made Mr O’Brien think that death didn’t mean anything to him.

The gunman was erratic. He was calm sometimes and shouting at people at others.

When he said “your deaths will be on Tony Abbott’s hands”, it gave Mr O’Brien the feeling that to the gunman, everyone in the cafe was expendable - and that he had to make his move and get out of there with his life.

The gunman wasn’t paying much attention to Mr O’Brien and the 83-year-old took advantage of the lack of attention crept closer to the door.

Every now and then, the terrorist would look at Mr O’Brien.

In the early stages of the siege, Mr O’Brien noticed that the gunman was very sharp and alert and had his eye on everyone.

But as the ordeal wore on, the gunman’s attention started to lapse by 2 or 3pm.

Mr O’Brien knew his captor would have to starting to tire. The 83-year-old hadn’t seen him eat or drink all day.

He kept edging towards the door, but inched towards it one time too many and was spotted.

Mr O’Brien was now looking down the barrel of the terrorist’s gun.

“I thought I told you not to move,” he yelled at Mr O’Brien.

The elderly man was terrified. He was going to be blown away there and then.

But for whatever reason the lunatic pointing the gun at him didn’t pull the trigger.

When the gun was finally lowered, Mr O’Brien sat still and composed himself.

It wasn’t long before he was again continuing his perilous journey towards the door, one millimetre at a time.

When he was finally close enough, Mr O’Brien made the pact with Stefan the lawyer that it was time to escape.

Mr O’Brien squeezed his body through the gap in the partition near the front door and the lawyer followed him. Had they been seen? They didn’t know. But they hadn’t been shot, so they kept moving.

As he smashed his hand onto the green button next to the door, Mr O’Brien was terrified that it wasn’t going to open the door and their names would be etched in history as the first victims of a trigger happy terrorist.

Relief would have flooded over Mr O’Brien with the doors finally slid open, but he had too much adrenaline pumping through his system.

The two men ran out onto Phillip St where the police were waiting.

It was 3.35pm.

Jarrod Morton-Hoffman

JARROD Morton-Hoffman has dealt with his fair share of difficult customers, but none like the man who sat at table 36.

When this pudgy, stubbled individual with the strange accent sat down, the 19 year old simply took him for another one of the hundreds of people he’d be serving that day.

The man ordered a valour chocolate cheesecake, and by the time Jarrod returned from the kitchen, had shifted to table 40 and was locked in deep discussion with manager Tori Johnson.

“I just thought he was another complainer,” Jarrod said of the man, who was wearing military-style pants.

Tori then waived for Jarrod to come over, and as he approached he could see that his boss was very distressed and blinking a lot.

The man sitting opposite Tori was staring up at Jarrod when he arrived at the table.

Tori then leaned over to his staff member and in a hushed voice said: “I need you to get my keys from the office and lock the doors. We’re closed. Everything is OK. Tell all the staff to be calm.”

Jarrod carried out his bosses’ orders, directing fellow staff member Joel Herat to lock the side door.

He then got a sign to say that they were closed and motioned toward to the front door to display it.

He looked over and saw this man had changed into black vest with lots of pockets and an Islamic bandanna.

“What are you doing?” the man said to Jarrod.

“I am putting the sign,” the young man replied.

“No you’re not. Sit the f*** down,” said the man, who was now holding a single-barrel shotgun.

For Jarrod the penny had finally dropped. This guy was no cranky customer, but rather a terrorist thug about to unleash hell.

This man, who Jarrod would later find out was Man Haron Monis, then told his terrified hostages that this was an Islamic State attack on Australia, he had two bombs, and that his “brothers” also had bombs.

The gunman then ordered Jarrod to move to the window of the Lindt Cafe.

“He threw me a black flag and told me to hold it up to the window,” he said.

“I recognised it as the ISIS flag. I held it up to the glass window, but he got angry at me because I held it up upside down and then back to front.

“He was trying to win us over, like some kind of Stockholm Syndrome.

“He kept giving us rewards and gifts to try and win us over and brainwash us.”

Monis starting ranting about the corrupt government and biased media, before ordering barrister Julie Taylor to call the ABC, SBS and 2GB.

Monis sacked her soon after because she was stuttering and too emotional.

Calm and composed, Jarrod volunteered to be the one to be “the caller”.

The University of Technology Sydney student was then told to speak to Ray Hadley, his own family and human rights organisations - to purportedly show Australia was committing a war crime by not helping the hostages.

As the hours ticked by Jarrod’s role evolved to one he called “researcher” where he would inform Monis of the content of media reports.

“When my phone lost charge I was worried that I would become redundant in his eyes and therefore vulnerable,” Jarrod said.

“The ‘redundant’ people were being used as shields or near him, but I wanted to be one of the ones doing things so I could be close to the side entrance because I knew it was unlocked.

“The people doing things had more freedom.”

“I am putting up the sign”

Jarrod soon realised, however, that the end of his phone’s battery life was the beginning of his escape.

Jarrod’s role became more prominent in the late evening as he ferried people to and from the toilet.

This allowed him and Fiona to slowly move things out of the way of the side entrance to assist in a possible escape. He also told others that this entrance was unlocked.

Monis also made Jarrod go searching for phone chargers and during one of these trips he stole a knife and hid it in his pants.

He also stole the basement keycard from the manager’s office, with the intention giving it to police so they could get into the building.

As the clock his 2am Monis was becoming increasingly paranoid. He took three hostages, including Jarrod to near the side door to look out the window.

Monis then walked into the kitchen, and with that move Jarrod knew he could escape.

Jarrod eased the side door open with his back and went into the atrium. He noticed fellow employees Joel Herat and Harriette Denny were behind him.

He went up to the double doors and for a few heart-stopping seconds was unable to open them because of he failed to find the release button.

“As I was about to exit I heard a loud bang and the glass shatter from the gunshot,” he said.

“I just ran outside and saw the armed police and ran straight to them.” It was 2.03am, and Jarrod was free.

Jarrod was among a small group of escapees who were taken to a “safe location” where they were given bottles of water and questioned by police.

He filled out a number of forms, was photographed, and handed over his clothes for forensic testing. They gave him a forensic jumpsuit and he left a few hours later.

Joel Herrat

LINDT Cafe waiter Joel Herat often uses a Stanley knife to cut ribbons and boxes.

He never thought he’d ever contemplate using it to stab a man in the neck.

That was the decision he’d soon be faced with, however, when he arrived for work five minutes before his 9am shift started.

The 21-year-old business and commerce student dropped his phone and wallet in the upstairs change room and began his shift.

This morning he was on the retail counter of the cafe, recognising a number of regular customers as he worked.

At 9.30am he first noticed a man of middle eastern appearance, who he would learn was Man Haron Monis, sitting at table 36.

He had a big black backpack, camouflage pants and a black adidas cap. He had a cup of tea and valour chocolate cake in front of him.

It was at about 9:45 am that he remembers ‘things’ started happening.

Monis was now sitting opposite manager Tori Johnson at table 40, a booth spot in the corner of the cafe near the lift lobby.

While he was standing in the kitchen looking over the dining area Mr Johnson said to fellow waiter Jarrod Morton-Hoffman: “Jarrod, can you come over here please”.

A short time later Mr Morton-Hoffman, 19, walked into the kitchen where Mr Herat was standing.

He then gave Mr Herat a Stanley knife that was 20-30cm long as well as a pair of red handled scissors of a similar in size.

As Mr Morton-Hoffman handed them over he said “dude, have these just in case. Something doesn’t feel right”.

Mr Herat stashed them both down the front pocket of his apron.

Monis, who didn’t see the exchange, pulled out a shotgun moments later and yelled “there is a bomb in the building. Everyone needs to do as I say.

“Australia is under attack. This is an ISIS attack on Australia.”

At this time, the doors were closed and the café was ‘locked down’.

Monis started asking questions about the access available to the people in the café. It was a group conversation with the gunman.

About 9:50am, Monis asked everyone to sit near tables 1-12.

At this point he removed his hat and revealed a black bandana with white Arabic text imprinted on it.

“When I heard and saw what the gunman was doing I thought it was a terrorist attack,” Mr Herat said.

“I was freaked out and very scared. I could not believe what was happening. I was in a state of shock.

“A short time later all the Lindt staff were asked to sit at table 12, which is in the corner near the marble display stand.”

Everyone moved except Tori Johnson, who was ordered to stay at table 40.

Yelling over the audible crying of Harriette Denny, who Mr Herat was now comforting, Monis then told everyone to put their wallets and phones on the table.

Seven hostages did, but when Mr Herat failed to, Monis asked him: “where is your phone and wallet?”

“I don’t have it, it’s upstairs in my bag,” he said.

Numerous times hostages were told to move, close their eyes and put their hands up and down.

Sometime before lunchtime Mr Herat noticed that fellow waiter Fiona Ma was being treated differently to everyone else.

She was allowed to walk unescorted to the kitchen and toilet, and was tasked with bringing people water and chairs.

“I think the gunman trusted her early on,” Mr Herat said.

At about 11am Ms Ma was ordered to escort Mr Herat from the ‘pick and mix’ area near the main entrance, to a spot near one of the windows which faced the Channel 7 building.

About an hour later he asked to go the toilet and was escorted by Ms Ma.

When they were alone he asked her: “Are you alright? What do you want to do? Do you want to escape? Do you want to run? What do we do?”

“I don’t know what to do,” Fiona said.

They kept the conversation short and returned to the cafe.

Mr Herat was one of the many hostages to speak with police negotiators, passing on Monis’ demands for an on-air phone call with Prime Minister Tony Abbott and an ISIS flag.

At about 5pm Mr Herat was standing with his eyes closed facing one of the windows. He then heard a loud rumbling sound.

He turned and saw a man in a white shirt, who he would later learn was Stefan Balafoutis, escape through the main entrance.

A visibly shocked Monis then pointed at Mr Herat and ordered him to walk over to him.

“I was really scared and thought he was going to kill everybody, including myself,” Mr Herat said.

Monis then said: “the police must have done something. Someone must die. You need to tell me these things.

“I could have done something stupid. I could have shot you.”

Mr Herat said: “dude, the police cannot come in from the entrance of the glass doors.

“The only way out was through the marble area.”

He told him that for the doors to open someone has to press the green button from inside the cafe.

After this Monis, who by this stage was being called “brother” by all of the hostages, instructed Ms Ma to take Mr Herat’s apron off.

She complied, without the terrorist noticing the knife and scissors secreted in the pocket.

At about 6.50pm Monis instructed Mr Herat to call Channel Ten so he could make the same demand for a chat with the PM and an ISIS flag.

He was sacked from the role almost immediately, however, because Monis believed he had a better chance with the females of the group.

Mr Herat was also forced to record one of the videos on Marcia Mikhael’s white coloured iPhone.

During the filming of one video, Viswa Ankireddy, who has a dark completion, could be seen holding one of the black flags.

“They probably think he is the brother,” Monis said while watching the video played back.

Mr Herat said: “you can take his clothes and get away if you want”.

Everyone had a laugh, including Monis.

While the videos were being filmed, Mr Herat was asked to cover the window.

Because the flag was being used in the video, he used his apron to cover the window. “At that time, I was thinking I could probably stab him as I had access to the Stanley knife and scissors,” he said.

“However I could not bring myself to do it.”

About 7:30pm, the gunman turned on the radio on via someone’s phone.

He was listening to the news. Every time someone spoke to the media, the gunman would tell them to say ‘He is treating us well, giving us food and water, letting us go to the bathroom’.

His mood and temperament changed depending on how the media were portraying the situation.

Just after, Mr Herat put his apron down near Monis. The terrorist picked the apron up and “by fluke” he grabbed it where the pocket was.

The Iranian-born Monis felt the shape of the scissors and took them out of the apron.

“Have you had these the whole time?” Monis said.

“Yes, I’ve had them in my pocket the whole time,” Mr Herat said.

“I was cutting ribbons before this happened. I wouldn’t do something stupid.”

Monis threw the scissors in a nearby bin. He didn’t find the knife.

Throughout the siege Monis gave people various roles: flag bearer, media caller, media researcher, cameraman etc.

The toilet chaperone, food or drink duties, however, were only performed by Ms Ma.

Mr Herat said most of the time Monis would whisper instructions into Ms Ma’s ear.

“While the roles were being explained, the gunman began talking about a credit system,” Mr Herat said.

“The credit system was based on how much you did. If you had more credit, you had more chance of being let go.”

Soon after 7.30pm lights in the cafe were switched off. About 15 minutes later, the gunman started commenting he wanted to have a cigarette.

He was concerned that the fire alarm so would go off and the sprinklers would come on.

Mr Johnson confirmed the alarms would still go off, even if the air vents are wrapped in plastic.

“The alarms do go off,” Mr Morton-Hoffman said.

“If you put the gun down I’ll give you my umbrella.”

Mr Herat smirked, but said he was too scared to laugh because “I was fearful of the gunman”.

As the clock ticked past 10pm Mr Herat became increasingly tired and exhausted.

He admits he would often “zone out”.

Monis instructed Mr Herat to move tables and chairs around people, he believes for them to be used for barricades.

“I was so tired and exhausted, I just complied with any request he made,” Mr Herat said.

Monis dangled the carrot of releasing hostages, saying if anyone was to leave, it would most likely be Mr Morton-Hoffman and Ms Ma.

Despite this, Mr Herat still didn’t believe what he said because he “would kill us all in the morning anyway”.

“He had been making promises all day that he had not kept,” he said.

“I just didn’t believe what he was saying. The gunman was acting strangely; kind one minute, erratic the next.”

Between 10pm and 11.30pm he saw Marcia Mikhael, Selina Win-Pe, Tori Johnson, Harriette Denny and Vishwa Ankireddy make phone calls.

He said he didn’t make any phone calls. His phone was still in the change room upstairs.

“I heard people telling their families their last goodbyes,” he said.

“I noticed that everyone was very visibly upset after making their phone calls. I saw them crying. It was very depressing.”

At about midnight Mr Herat asked the gunman if he could go to the bathroom, with Monis agreeing as long as Ms Ma escorted him.

At this point he was desperate to grab his phone and wallet. Ms Ma then agreed to take him to the locker room.

While they were walking there, Ms Ma said “are you okay, What do you want to do?”

Mr Herat said: ”I don’t know what to do but we have to escape. Try to get the word out.”

Mr Herat said he genuinely believed Monis was going to kill everyone by the morning. Every noise was setting him off and he was highly paranoid.

Mr Herat dozed off for about 15 minutes before waking at about 1.55am. The first thing he saw was Mr Morton-Hoffman standing with his hands up near the exit to the lift lobby.

The gunman had again become paranoid about the ice machine, taking Ms Ma and Selina Win-Pe with him as human shields.

When Monis was out of earshot Harriette Denny said to Mr Herat “move your chair towards that way”, pointing towards the entrance door.

“I’m not leaving you,” Mr Herat said, not wanting to leave someone behind who he described as being “very close to”.

He refocussed on the location of the gunman, Ms Ma and Ms Win-Pe.

They were walking very slowly towards the entrance of the kitchen.

He saw them stop there for a short period before changing direction past the barista area towards the fire exit.

They continued walking in silence. No one was talking at all. Everyone was quiet.

With a clear path to the exit, Mr Morton-Hoffman said “I’m gonna go get help”.

Mr Morton-Hoffman then forced open the door than runs between the cafe and the lift lobby.

Mr Herat then grabbed Ms Denny and ran through the same door.

As they ran through they heard a gunshot.

He saw Mr Morton-Hoffman hit the green button on the second door which opened onto Martin Place.

“That door was still open and Harriette and I ran through it,” Mr Herat said.

“I turned left. I saw some police and ran straight to them with my hands in the air.”

Police then took Mr Herat and the other hostages who had escaped to the nearby NSW Leagues Club on Phillip St.

He gave his clothes over to police and was given a forensic jumpsuit. He answered some questions about the gunman and the event before leaving at about 6am.

Mr Herat said that he has been deeply scared and traumatised by the experience.

“I feel guilty for leaving someone behind,” he said.

“I have to live with that for the rest of my life. I am struggling to sleep, it’s always on my mind, I get a lot of flashbacks, reliving the scenario, thinking if only I did this or I did that.

“A lot of my friends at the café were there and we can all relate. I feel for my friends and their families.

“My family are constantly worried and distressed. It has affected everyone in my family.”

Paolo Vassalo

PAOLO Vassalo walked into the Lindt Cafe at Martin Place early on December 15, 2014, and found himself faced with the usual set of dramas.

The 36-year-old qualified chef had worked at the cafe for two years as its backhouse supervisor, meaning he was responsible for stock control and ordering.

He had started most days since by having “a whinge” to the cafe’s manager Tori Johnson about staffing issues, usually for no result.

He was supposed to get one or two assistants to help present the pre-prepared food after it was delivered each morning. But when there was a shortfall in the staffing in the “front of house” operations, it was always his help that got pinched, leaving him even more understaffed.

Today was shaping up as one of those days.

He arrived at the cafe at 6.44am - 16 minutes early.

Tori greeted him at the front door and they shared a few stories about their weekend.

The morning went quickly with Mr Vassalo was dealing with each delivery just in time for the next one to arrive.

His flow only interrupted by his colleague, April, who came into the kitchen to talk about her latest holiday.

Mr Vassalo searched his memory bank for her surname but drew a blank. She had been away and it may have been her first shift back at work. He couldn’t remember.

By 9.30am Mr Vassalo had dealt with the croissants and checked the clock to see how long it was until some assistance arrived.

Twenty minutes later, Jarrod Morton-Hoffman, one of the cafe’s junior employees entered the back office before entering the kitchen where he asked Mr Vassalo: “Which one is Toris’ bag?”.

Mr Vassalo pointed towards the bag and Jarrod reached in and pulled out a set of keys attached to a silver BMW keyring.

Jarrod turned to leave in a hurry and Mr Vassalo asked him: “Why do you want the keys for?”.

“Tori said we have to lock the cafe down,” Mr Morton-Hoffman replied before leaving at pace.

“Something must be wrong,” Mr Vassalo. thought “Why close the cafe at this time of year when we’re this busy?”

He could see a man with a shaved head sitting in a ute outside on Phillip St. It looked like an Armaguard ute. Was someone was robbing it?

With no action outside, Mr Vassalo turned and looked across the cafe and saw about eight people standing up in what looked like a close circle.

“This just doesn’t look right,” he thought.

He walked three or four steps toward the group when he saw it: a male standing in the middle of the cafe holding a long gun.

It was too late to flee.

The man with the gun spotted the chef and ordered him to sit with the rest of the people around a table behind the register.

The gunman appeared to be very composed and before long had all of the prisoners to putting their drivers licenses on the table.

It would be several hours before Mr Vassalo would learn his captor was Man Haron Monis, a deranged parasite who had recently hitched his wagon to the murderous pursuits of ISIS.

For now, Ms Vassalo knew him only as “the man with the gun”.

The chef took his license out and obediently placed it on top of his wallet on the table.

It made Mr Vassalo feel uneasy when the gunman didn’t bother checking the IDs and only asked “who were cops?”.

Soon after, the man ordered Mr Vassalo and the rest of the hostages to close their eyes and arranged in them in positions where they lined the windows of the cafe looking out over Martin Place.

With his hands in the air, Mr Vassalo snuck a look and noticed he was standing next to Joel Herat, another colleague at the cafe, with Tori behind to his right.

Minutes later, the gunman grabbed Mr Vassalo by the back of his shirt near his collar and moved him away from the chocolate platform.

“Here, here,” the captor said, jerking Mr Vassalo into position.

It wasn’t long before the gunman spoke again: “You will all walk out of here today. The only reason you will die is if you try to escape or the police get too close. I don’t want to harm you.”

He then ordered a number of the people to hold up a black flag in the window.

When a female started screaming that she needed her medicine, Mr Vassalo heard the man tell her: “We’ve got a radical Aussie here. You’re going to be the first one to go”.

“She’s going to be the first to die,” Mr Vassalo thought.

Three hours into the siege, Mr Vassalo saw the reflection of people outside and was certain he could see a person with a shield. It had to be a police officer.

Later, another person held what looked like a mobile phone up to the window. Were they filming something? Whatever it was, it made Mr Vassalo feel safer. Surely it meant someone was doing something to save them.

Mr Vassalo was sceptical of the gunman’s claim he was carrying a bomb. He concluded the only way he was going to die was if he was shot by his captor or the police when they inevitably stormed in.

Not for the first time, the gunman talked about getting the bomb he claimed to be carrying disarmed. One of the hostages offered to take the bomb to the cafe door and pass it to police to have it defused, but the offer was refused.

Later, the gunman got into an argument with Tori when he thought a camera mounted on the cafe’s wall was recording the scene unfolding. Tori told him the camera didn’t work and was ordered to turn the television on.

Mr Vassalo watched on as Tori said the TV only played advertising for Lindt.

The gunman replied: “If you’re lying to me you will die”.

When the TV was turned on and nothing appeared on the screen, the gunman said: “very good, manager, you are an honourable man”.

A moment of respite finally came when their captor asked who needed to go to the toilet. Mr Vassalo raised his hand.

Mr Vassalo felt someone grab him on his back and move him towards the toilet. He made sure to feel his way with his arms outstretched so the gunman would think his eyes were still closed.

AS he turned the corner, Mr Vassalo opened his eyes and realised the person leading him was Fiona Ma, his colleague at the cafe.

Mr Vassalo made small talk with Fiona and noticed a missed call from his wife on the phone that the gunman hadn’t confiscated. He decided it safer if he didn’t attempt to call or text anyone.

Back on the window the gunman was shuffling the order of where the hostages were standing. Several times Mr Vassalo pretended to bend over and clutch his stomach as if he was very afraid or had physical problems so the man would leave him alone.

After an hour Mr Vassalo told the gunman he needed to go to the toilet again.

“Why do you need to go again so soon?” the gunman demanded to know before allowing the request.

On the way to the bathroom, again being led by Ms Ma, he noticed an escape route at the end of the corridor.

He knew he could get out before that lunatic could catch him, he told himself.

After pretending to use the toilet, he went back to the sink area and gave Fiona a hug and a kiss.

“We can get out by going back through the kitchen and out the fire escape,” he told her. “I’m not going to leave you here to die.”

He tried to convince Ms Ma that they could get to safety, but she was stuck on one point.

“If we escape, he’s going to kill the rest of the hostages,” she said.

As much as Ms Vassalo tried to change her mind, Ms Ma refused go through with his escape plan. He gave in and let her lead him back to the cafe to his original position.

An hour or so later, Mr Vassalo heard commotion and the sound of running. He spun around to see an old man and another man, who was wearing a white shirt, run through the front doors and onto Phillip St.

Mr Vassalo rued that it could have been him getting out, but he had let Fiona talk him out of it.

The gunman didn’t kill anyone after the escape, but brought the hostages in closer.

Mr Vassalo had one thought on his mind: “I have to leave now or I won’t get another chance”.

Thirty seconds after the two men had escaped, Mr Vassalo made his decision to go.

He turned and walked quickly, zig zagging his way towards the kitchen opening before turning left and running up the three or four steps.

He then pushed the emergency bar on the fire exit door and burst onto Phillip St and certain freedom.

The first thing he saw was “a group of surprised police officers in grey clothing” as he came through the door and set off the fire alarm.

The next person he saw was the man in the white shirt who had escaped earlier. He was Stefan Balafoutis.

They hugged and acknowledged they had made it out alive.

The next person he saw was a police officer.

“You’ve got to go in there now,” Mr Vassalo urged him, knowing it wasn’t the officer’s call to make.

Mr Vassalo was taken to a loading dock on Phillip St where he called his wife.

Police then took the chef further up Phillip St to NSW Leagues Club where ambulance officers were not happy with his vital signs and transferred him to St Vincent’s Hospital where he was hooked up to machines.

Still in the hospital at 7.05pm, he received a text message from Tori, which read: “Tell the police the lobby door is unlocked. He’s sitting in the corner on his own.”

It was the last contact he ever had with Tori.

The siege changed Mr Vassalo.

Unable to sleep, he was prescribed sleeping pills.

He suffered constant flashbacks to the scene and thought about little else.

His mother and father suffered similar symptoms.

At shopping centres, Mr Vassalo heard people talking about the siege and had to flee.

He told police officers in his interview: “I feel I cannot leave my home for fear of being recognised and someone wanting to talk about the siege with me”.

Marcia Mikhael

MARCIA Mikhael made two decisions on the morning of Monday, December 15.

Both were seemingly trivial, but both would ultimately lead to her being carried from the Lindt Café bleeding, terrified, but alive.

The woman police would find at her side, mother-of-three Katrina Dawson, would not be so lucky.

The Westpac senior IT project manager works between two offices – one on Kent St and the other in Martin Place – and she was due to go to Kent St that morning.

At the last minute she changed her mind, however, and went to the Martin Place office.

Ms Mikael is well-known in the office as a devoted lover of Lindt chocolate, and so almost always goes to the cafe.

This day was different.

“I wasn’t going to go to Lindt that day as I was trying to be healthy,” she said in her statement to NSW Police.

“My work colleagues Puspendu (Ghosh), and Viswa (Ankireddy) convinced me to go, saying that it was close to Christmas and that I loved Lindt and we should treat ourselves.”

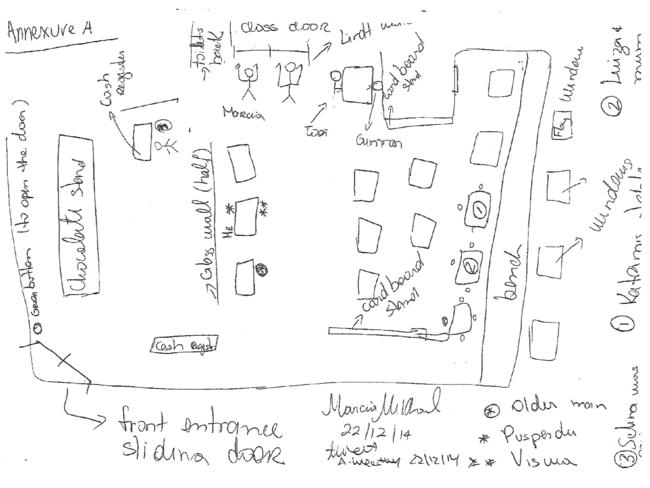

So the trio walked 75m from the office to the café, arriving sometime between 9.30am and 9.45am.

The group visit so often they joke that they have a regular table where they sit, and this morning was no different.

That table is next to the manager’s table, where they often see him having a coffee while he does his bookwork – always alone.

But this was not a regular day.

Ms Mikhael noticed that the manager, whose name she would later discover was Tori Johnson, was sitting opposite a man who had a large cotton Big W bag sitting on his lap.

Although his presence and the table and the bag struck her as unusual, she assumed that this “scruffy looking” man in his early 40s was making a customer complaint.

Johnson was meanwhile on the phone with his head in his hands, while also whispering instructions to his staff in the interim.

As per Tori Johnson’s instructions, staff went about locking first the sliding door near the atrium, then the main entrance to the café off Martin Place.

Ms Mikhael saw people knocking on both these doors from the outside in an effort to get in.

When a customer tried to leave – who she would later discover was Selina Win-Pe – Ms Mikhael pointed out the manager so she could get him to open the doors.

“At this point the gunman stood up and got the shotgun out of the Big W cotton bag,” she said.

“He pulled it out right in front of me. I would have been about 2m away from him.”

It was only then that she realised her decision to go to the Lindt Café that morning would change her life forever.

“After the gunman had told us he was there to keep us safe I distinctly remember him saying: ‘If anyone tries to escape I will kill somebody’,” the 43-year-old said.

The man, who Ms Mikhael would later learn was Man Haron Monis, started speaking about his “brothers” who also had bombs.

He heard over the radio that there had been a bomb hoax in Parramatta and so made a comment “maybe the brothers had changed their mind”.

In an effort to placate him, the hostages referred to him as “brother” for the majority of the siege.

When Monis started handing out the flags to be held up against the windows, Ms Mikhael, whose father is Lebanese, recognised the Arabic writing.

She was moved against the side door near the manager’s table and told, along with everyone else, to face outwards with her eyes closed.

This was the side door where the lock was up the top and all that needs to be done to unlock it is to pull the latch down.

She was so close to freedom but so far from escaping.

“I was terrified and crying and I just wanted to go home,” she said.

“I thought I was standing in the spot that may have been the easiest to escape as I could have just pulled the lock off the door and I would be out.

“But I was frozen with fear after the threats that were made earlier by the gunman about how he would shoot anyone who tried to escape.”

When she was standing at the door Ms Mikhael realised that Monis could not see her.

She opened her eyes, and could see a uniformed policeman standing against the wall outside.

Crying and distressed, the policeman gestured for her to breathe deeply and calm down.

Once she stopped crying the policeman asked ‘how many?’

She put up one index finger on her right hand to indicate one.

He then asked about a gun, and so she nodded her head and mouthed ‘yes’ to indicate that he did have a gun.

He asked ‘where is he?’

“I pointed to the right with my index finger and he was hiding in the corner,” she said.

“The police officer used his hand gestures again to try and calm me down and comfort me. But then he disappeared from my view and I didn’t see him again.”

Earlier in the day Monis demanded all hostages put their phones on the manager’s table, the same table which Ms Mikhael had been sitting next to at the start of the day.

While she was on her way to the toilet some time later, Ms Mikhael managed to take back her mobile phone from that table.

While in the toilet she texted her husband George Mikhael and a few others, saying ‘At Lindt hostage’.

“I remember that I was shaking so much while writing it,” she said.

Family and friends had also been trying to contact her.

“I remember there being so many text messages, but I couldn’t reply as I was taking too long in the bathroom,” she said.

When Ms Mikhael returned she volunteered to help Selina who had become sick.

Trained in first aid, she left the spot she was in close to the door and went to help the girl who was hyperventilating.

This decision would prove pivotal later on, as from then on she got “stuck with the gunman” next to Katrina Dawson.

She never returned to the door through which many of the hostages would escape.

Ms Mikhael admits that her concept of time was blurred during the siege. Because Julie Taylor was 19 weeks pregnant, Ms Mikhael volunteered to take over the role of holding the Islamic flag on the window.

During this time five people escaped. A very angry Monis said that he would shoot a hostage for every one that escapes.

Ms Mikhael then watched as Monis grew angrier at Jarrod, who appeared to be getting nowhere with his requests from police for a live conversation with Prime Minister Tony Abbott and an Islamic State flag.

Ms Mikhael wanted to “get out of there” and get home to her kids and so volunteered to be the hostage who would call media and the police.

She was instructed to speak to numerous media outlets and the police about getting the Prime Minister on the phone to Monis and to get an Islamic State flag.

“I repeated this same phrase numerous times to many other people that day,” she said of the request for the PM and a flag.

“The gunman told us what to say about the demands and things he wanted, but I added the bit about ‘why haven’t his demands been met?’

“I was angry and shaking. I was frustrated and yelling at a lot of people.

“I couldn’t understand why these demands hadn’t been met. They seemed simple enough to me as he only wanted a phone call and a flag.”

Monis initially praised Ms Mikhael for “being strong” but soon became angry with her because she was encountering the same resistance as others had before.

He soon had another role for her - that of being in his 30-second videos which would be sent to TV channels and YouTube.

For the videos she was instructed to state her name, that she was a hostage in the Lindt Cafe and that “the brother” demanded to speak with the PM, obtain an Islamic State flag and to “communicate with his brothers via the media”.

These video files were then emailed to the television stations. One hour later Monis instructed Jarrod Morton-Hoffman, 19, to upload the videos to YouTube.

The hostages were fearful of repercussions if Monis found out that the videos were not played on TV.

Knowing that he was not tech savvy, they engaged in some honourable teamwork.

“We all knew that you could get TV online but we told him it was impossible to get it on our phones,” she said.

“If anyone said to him something we all went along with it, especially in terms of the TV on mobile phones.

“Some of us either didn’t know or they knew things but we didn’t want to tell him everything.”

As it got later in the evening and into the early morning there were long stretches of silence, punctuated by Monis’ paranoia about every sound.

He also made small talk with Ms Mikhael, asking her how many kids she had, their ages, and what she did for work.

She told him the truth about her three sons because “I didn’t think of lying”.

But there was one thing she definitely did not want Monis to know.

“I was just praying at this stage that he didn’t find out I was Lebanese Christian,” she said.

“That would have made him very angry as being an extremist Muslim, they don’t like Christians.”

Then more silence, where some hostages tried to get some sleep, including 21-year-old Lindt Café waiter Joel Herat.

At about 2am the gunman then heard a noise at the back of the café, so he took Selina and Fiona along with him to the kitchen.

While Monis was in there Jarrod Morton-Hoffman, Joel Herat, together with Ms Mikhael’s colleagues Puspendu Ghosh, and Viswa Ankireddy, escaped.

The gunman came back into the café and fired off a shot from his single-barrelled shotgun.

“This is when I ducked onto the ground,” she said.

“I went underneath a table which was close to me. I saw Katrina (Dawson) duck down underneath the two seats we had been sitting on.

“I would have been no more than a metre away from Katrina; we were pretty much laying side by side one another.”

Manager Tori Johnson had been mostly quiet throughout the whole siege and was seated on a bench.

Monis was now standing in the middle of the café and said to the manager: “Get up and come over here”.

Ms Mikhael was on the ground alongside Katrina Dawson, 2-3m behind the gunman.

On a nearby table there was a phone which kept vibrating.

“I remember Katrina and I looking in despair at one another thinking ‘this is it, this is the end’,” she said.

“The gunman must have seen movement outside or something. That’s when the gunman fired the second shot. The shot gun was deafening.

“After that, that’s when the fireworks started.”

Ms Mikhael remembers shots being fired from both inside and out, with the sound of “little grenades” going off everywhere.

It was during this time that Ms Mikhael was hit in the left leg by bullet shrapnel, describing it as a “burning sensation”.

Realising that she was in the line of fire, she moved forward along the wall and scrunched herself into a tiny ball.

“I was in a lot of pain (and) I just closed my eyes and stayed there, hoping it would all end,” she said.

“I looked at Katrina across from me and I noticed she wasn’t moving.”

Shortly after police came to Ms Mikhael’s aid she told the officers to take Katrina because she wasn’t moving.

“I was being carried out of the café one police officer on either side of me as I couldn’t walk,” she said.

“I looked down on the ground and saw the gunman with half his brain hanging out of his head.”

After being dropped outside the café by the police she looked up at them and screamed “get me the hell out of here!”

Ms Mikhael was handed over to paramedics and taken to Royal North Shore Hospital, where she was treated for multiple shrapnel injuries on both her legs from the knee down.

Her left leg was the worst affected, requiring surgery plus skin grafts.

She stayed in hospital until the following Monday, December 22.

Most of the shrapnel in her leg has been left there because it would cause too much tissue, muscle and nerve damage if they try and take it out.

She has lost sensitivity in her right foot because of nerve damage. But she is alive.

Louisa Hope

LOUISA Hope looked outside the Lindt Cafe and it was definitely night time.

The siege had been going for about 15-and-a-half hours and the 52-year-old noticed there was a bit of a lull in the atmosphere inside the cafe.

The group of hostages as a group had run out of ideas and were exhausted.

They had spent the day trying to get the gunman’s demands met. Attempts to contact the media to broadcast his message had failed, as had their efforts to post videos to social media and have them stay there.

But after almost 16 hours, this maniac who had been holding them hostage at gunpoint still hadn’t had his demands met, which included speaking to Prime Minister Tony Abbott.

“He hasn’t said what would happen if his demands weren’t met but did say he would release hostages if they were met,” Ms Hope thought.

Ms Hope racked her brain but drew a blank as to what they could try next.

One newsroom had told a hostage over the phone that they couldn’t put them through to anyone that could help and hung up.

The hostages had tried all the local networks and went as far afield as trying to call Al Jazeera and the BBC for no result.

Attempts to call 1800 numbers listed on overseas news websites had failed because they were calling from a different country.

Ms Hope didn’t know it, but the lull was about to be broken. The siege was 30 minutes away from reaching its dramatic and violent conclusion.

She surveyed the scene inside the cafe and it appeared to her that the gunman had positioned all the tables and chairs in a big circle to protect himself from gunfire that could come at any time from outside.

“It’s like he’s trying to create a sense of protection for himself,” she thought.

People weren’t sleeping, but they appeared to Ms Hope to be dosing.

She couldn’t’ tell if the gunman was in the same sort of lull, or if he was alert. He was sitting in the back corner of the cafe on a bench and had placed three female hostages seated around him for protection.

Ms Hope remembered their names were Selina, Katrina and Marcia.

The two Indian guys, whose names she couldn’t remember, were seated closer to the door.

Then there was Jarrod and Fiona seated on the outer rim of chairs.

Joel was positioned halfway between Ms Hope and the rest of the group.

“He looks dozey as well,” Ms Hope thought.

Ms Hope’s mother, Robyn, and Tori, the cafe manager, were seated on the bench, which had the tables in front of them.

And to the right of Tori was where Ms Hope sat.

The gunman started to hear noises from the kitchen, which annoyed him and put him on edge. The ice machine had been going off all day but he hadn’t caught on and still thought it was the police.

“You’d think he’d remember by now,” Ms Hope thought.

Another noise from the kitchen sparked the gunman into action. He got up and and arranged Selina, Fiona and Jarrod around him.

It looked to Ms Hope like he was arranging them as a human shield in case the police came in.

The gunman walked them towards a floor to ceiling partition, which was behind the front counter to the rear of the cafe.

Once the gunman and his human shield were out of Ms Hope’s sight, she closed her eyes and started praying to herself.

Three to four minutes passed. It was quiet and no one said anything.

Ms Hope’s quiet prayer session was broken by a loud bang.

It wasn’t as loud as a gunshot and it wasn’t a quick bang.

She opened her eyes and noticed that everyone she could see previously was gone.

It took a few seconds to register, but she was also staring at a set of glass doors, and they were open.

There had been another escape.

She came back to that thought again: “The doors are open”.

“Where’s the gunman?”.

Ms Hope paused for a second or two and instinct took over. She got up and ran towards the door.

She was almost through the doors and to the safety of the police outside when reality hit.

Her 72-year-old mother, Robyn, was still sitting in the cafe where the two had been held hostage for almost 16 hours.

“I can’t leave mum,” Ms Hope thought to herself.

She hit the brakes and turned back to retrieve her elderly mother.

Could she get her out too? Where was the gunman?

Ms Hope looked at her mother and knew she wouldn’t be able to get both of them out without being sprung.

She couldn’t leave her mother to be murdered by this monster.

If it was a choice of living the rest of her life knowing she abandoned her mother to be slaughtered or dying tonight, Ms Hope opted for death.

She turned her back to the door and went back to her spot in the cafe.

“We’re all going to die here,” she thought.

The 52-year-old laid down stomach first, put her face on the floor and placed her hands behind her head.

“This is as good as any position to die in,” she thought. “It’s only a matter of time before he comes back in and starts killing everyone.”

She could hear the gunman coming back.