Arrest could be key to Cheryl Grimmer’s disappearance from NSW beach

Three-year-old Cheryl Grimmer vanished from a NSW beach in 1970. For five decades her loss has haunted her surviving family and taunted cold case detectives — until the arrest of a man last February.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

CHERYL Grimmer vanished on a January afternoon in 1970. Her loss haunts her surviving family members and has taunted cold case police for five decades.

It happens exactly four years after the Beaumont children go missing from a beach in Adelaide. Four little children are playing on a beach and in a few terrible minutes their happy family is smashed forever.

This time, one child vanishes, not three.

READ MORE:

LITTLE JOHN LANDOS LOST, BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

THE FINAL MOMENTS OF MELBOURNE’S BLACK PRINCE

CARL WILLIAM’S AND THE HOUSE THAT DRUGS BROUGHT

Cheryl is youngest of the four their mother Carole Grimmer took to Fairy Meadow beach near Wollongong on January 12, a Monday.

The young mother, recently arrived from Britain, is staying at the nearby migrant hostel for a few weeks before moving closer to Penrith, where her husband has enlisted as a sapper in the Australian Army.

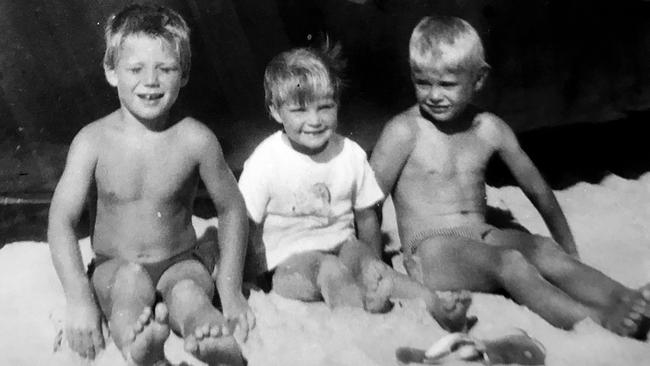

Around 1.30pm the weather changes and Carole sends her three sons — aged seven, five and four — to change into their clothes in the nearby shower block. “Baby” Cheryl, just three, tags along and goes into the change rooms with her brothers.

Soon after, the boys walk back to their mother but Cheryl doesn’t follow. Instead, it seems, she wanders in the other direction after being lifted up — to have a drink from a bubble tap — either by her brother Ricki or by “a man” or neither, depending on which confused witness tells the story.

Cheryl is never seen again.

In the next hours and days, hundreds of searchers comb every inch of the surrounding countryside. It seems unlikely they would miss a child’s body anywhere within walking distance of the beach. It seems unlikely they would not check every drainpipe or hole or hollow that could hide her.

And so it is natural to wonder if Cheryl was taken much farther away, by car.

It means that when more than one person reports having seen a small, dark adult man carrying a little blonde girl away from the changing rooms and driving off in a rusty, cream-coloured 1959 or 1960 Holden, police and the media seize on it as a strong lead.

Despite a detailed description, the man isn’t found.

Witnesses — including a former British serviceman and his family — say the short, slim, dark man is in his late 30s, wearing a floppy beige hat, brown or orange swimming trunks, short-sleeved cream shirt and thongs.

Police and reporters describe the wanted man as “Italian or Spanish” but note he speaks good English, indicating he must have spoken to someone. Young girls at the hostel describe a man matching his description accosting them.

MORE CONTENT:

YOUNG MOTHER’S BRUTAL DEATH SHOCKED ALL OF VICTORIA

RULE: THE CHILDISHLY IGNORANT WARPING THE ANIMAL RIGHTS DEBATE

SUBSCRIBE TO ANDREW RULE’S PODCAST ON iTUNES HERE AND RSS HERE

It makes sense that a man broadly described as southern European would be a migrant and most likely familiar with the hostel and the beach, perhaps from having spent time there in past years.

Meanwhile, there are other leads.

Police want to find the driver of a blue Kombi van seen parked near the shower block. And they start combing through a list of up to 200 known sex offenders in the Wollongong area.

As days turn into weeks and they don’t find the small man with his rusty cream Holden the list of potential suspects grows to at least seven.

There was, for instance, a man seen carrying a small girl on Mt Ousley, west of Wollongong. And witnesses report seeing a small girl answering Cheryl’s description walking behind a group of children elsewhere.

Nothing is clear in the fog of contradictory reports.

The description of the small, dark man and his rusty Holden is sent to every police department in Australia. From the first day it seemed the strongest lead — and, 48 years later, it still might be.

The Grimmer family moves from the Fairy Meadow hostel to Sydney to endure the rest of their lives. The husband trying not to blame his wife. The wife trying not to blame her eldest son. The son blaming himself for leaving his sister for a few minutes.

The couple pray for a miracle and don’t get it, hoping their girl had been raised by strangers and will turn up one day.

That is the tragic story of one English migrant family. It becomes intertwined with another that arrived the same year.

WE cannot name the suspect or his family. We will call him John Doe, a plain English name much like the one he and his father and stepmother brought with them on the liner Fairstar, which sailed for Australia from Southampton in 1969.

John Doe was born in the Royal Infirmery at Ashton-under-Lyne in Lancashire in February 1954. But his natural mother left his violent father soon after.

He had a few happy years with his grandmother before going to live with his father and stepmother.

They moved a lot and his father hit him a lot.

In letters shown to the Sunday Herald Sun, the adult John Doe describes being beaten and locked in cupboards and forced to sleep in wet sheets after becoming a compulsive bed wetter. His stepmother treated him better than his father did but it wasn’t good.

John Doe was 15 when the unhappy trio migrated on the promise of a job in South Australia for his father — a job that fell through.

By then John had attended a string of schools and his education was poor. He was of medium size, not small, with pale skin, another of the “ten pound Poms” who came south in the wintry decades after World War II.

That same year “Vince”and Carole Grimmer arrive from Bristol with their three boys and baby Cheryl. Vince goes to work at Penrith and Carole and the children stay temporarily at the Fairy Meadow hostel.

It’s the same hostel (John Doe would write in letters seen by this reporter) that he and his parents stayed for some time.

On his own evidence, John Doe knew Fairy Meadow beach. But he strenuously denies being there in January 1970, when Cheryl Grimmer went missing. By then, he says, his family had moved to Redfern.

Moving across the world did not make John Doe’s father any less violent, he says.

The boy ran away from home and when he was caught he was placed, with his father’s “blessing”, in the Albion Street boys’ home in Surry Hills.

It was there or in another boys’ home, he says, that he was attacked by older and tougher boys who attempted to rape him in early 1971.

The first anniversary of the Grimmer case had been huge news.

When the tough inmates, car thieves and burglars, asked him what he was “in” for, the frightened English boy claimed he had done a murder. Not any murder — the famous one in the papers, the Grimmer case.

As soon as the staff heard this extraordinary claim, they called the police.

Well-known Sydney homicide squad detective Joe Parrington drove the frightened boy to Wollongong and challenged him to prove he had done the murder by showing him which roads he had used, where he had hidden the body and so on.

His answers were jumbled enough not to satisfy Parrington or his sidekicks they were genuine.

Instead of taking a formal statement, John Doe says, the police asked him to pick the “best” answers from alternatives.

What colour bathers did the little girl wear: black or white? Did she have a drink at the bubble tap at the changing rooms: yes or no? Did you take her east or west? This road or that?

John Doe has told his wife he “took pot luck” and made haphazard answers that were meaningless. She says, “he just wanted desperately to get out of the boys home.”

At the time the police decided his answers were “inconsistent” with the facts and that he was a timewaster and a fantasist.

False confessions often waste investigators’ time in high-profile cases that attract the disturbed and the vulnerable, and at 16 years old John Doe was both disturbed and vulnerable.

The other problem for police in big cases is that they receive far too many “leads” to be able to check them all properly. The inevitable result is that vital information is lost.

THERE is no “smoking gun” evidence that Cheryl Grimmer was abducted and murdered, which is why a coroner avoided making a finding of homicide in 2011.

But the reality, of course, is that she was almost certainly killed shortly after vanishing from the changing rooms.

What is not certain is that the quiet middle-aged man that NSW detectives arrested last year is the killer.

That could change this week at a committal hearing in Wollongong District Court, when investigators get the chance to reveal evidence justifying their decision to arrest John Doe.

They made the arrest in Frankston in February last year.

The accused asked to come to the station to be interviewed.

He told his wife he had to drop into the police station on a routine matter to do with his work at a hospital. She did not know he had been arrested until he failed to come home that night.

By then, the NSW detective leading the investigation, Damien Loone, had been in Victoria for days.

He went first to the country town where John Doe had lived since marrying his first wife in the early 1980s, and where they raised two children before divorcing around 2006.

The detective got local police to introduce him to John Doe’s ex-wife and adult children.

He found Doe had worked in steady jobs, had been a volunteer ambulance member and had done the usual rounds of school and children’s sport. So far, so ordinary.

Doe’s ex-wife took Loone’s card and arranged to meet her former husband at a McDonalds in Frankston, pretending their daughter was ill.

She handed him the card and insisted he call Loone to talk about his past. He did, and that night found himself flying back to Sydney under escort — and with a reporter sitting near them who had been tipped off in advance.

More media were waiting at Sydney airport.

The arrest was big news, and Damien Loone was at the centre of it, the main man in a task force set up to get a result in the notorious Grimmer case.

The NSW police force’s legal department has backed the task force, apparently on the strength of a fresh analysis of the teenage John Doe’s half-baked “confession” in 1971.

The police and prosecution believe the 1970s detectives got it wrong, and missed vital evidence.

But the accused man and his second wife — and, presumably, defence counsel — believe he is a convenient fall guy for zealous investigators whose predecessors lost track of other suspects.

The woman married to the accused man has known him for 12 years, and lived with him for 10.

In the long months since his arrest early last year, she has visited him in Silverwater Prison in outer Sydney every two weeks, and has never stopped asking him questions and weighing his answers.

She has dozens of letters from him, and has shown them to the Sunday Herald Sun.

She works long night shifts and can barely afford the $500 cost every time she flies to Sydney then takes trains and buses to Silverwater, but her loyalty has never wavered.

Seventeen months is a long time to reflect on facts and on feelings, time enough for adrenaline to die and affection to wane and, perhaps, for a bleaker reality to creep in.

She says she feels the same now as she has since the shock of the arrest. But her love and loyalty is not the measure of her husband’s guilt or innocence or he would already be free. There are other considerations.

The prosecution might make something of the fact the suspect changed his name by deed poll in the 1980s, a decision his wife firmly believes was because he refused to pass on his hated father’s surname to his children.

The defence will be much interested in whether police have managed to eliminate any or all other suspects.

As recently as 2014 the Illawarra Mercury reported that three suspects were never formally eliminated from the investigation. One died in 1995; another was not found after being interviewed in the 1970s.

And there is another intriguing aspect — that of witnesses, some of them children at the time, who might be asked to clarify what they stated at the time, or to recall clearly the events of a few seconds half a century ago.

As an eminent defence barrister once stated, and some judges no doubt believe, “Beware the witness whose memory improves.”