A leading economist has come up with a radical plan to end Australia’s housing woes once and for all

A leading economist has a bold idea to finally solve Australia’s housing woes – and a country nearby has successfully done something similar.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A leading economist has proposed a bold plan to finally solve Australia’s housing woes – and a country nearby has done something similar with great success.

Cameron Murray, chief economist at Fresh Economic Thinking and author of the new book The Great Housing Hijack, said the model doesn’t need to be at the expense of the private market.

“Homeownership insulates you from rental market cycles, because if rents go up by 30 per cent but you’re in your own home, you’re free,” Dr Murray said.

“The way I see it, we’ve got a third of Australians in private rentals, but if that was reduced to 10 per cent, then the cost of market increases would be reduced by two-thirds.”

His proposal to achieve that is called HouseMate, which would see people able to buy their first home sooner, avoid the rental market for longer, and enjoy the stability that comes with both.

Within 15 years, Dr Murray forecasts that half of all renters could be out of a rental and into their own place – with some government help.

The idea would see cheap homes built on under-utilised Crown, council and federal land, as well as on plots acquired through compulsory acquisitions or purchased at market prices.

“HouseMate would sell the dwellings at a discounted price – $300,000 on average – to Australian citizens aged over 24 and in a de facto or married relationship, and to single citizens aged over 28 and over, where no household member owns property,” Dr Murray explained.

Loans would be underwritten by the Federal Government for up to 95 per cent of the purchase price and charged at one percentage point above the official cash rate.

At present, that would see participants paying back their loans at 5.35 per cent – a big saving on the standard variable interest rate of about 6.9 per cent currently offered by major banks.

“HouseMate buyers would be permitted to use their superannuation savings and contributions for both the deposit and ongoing repayments,” Dr Murray added.

“They will own the home freehold, paying council rates, insurances, and having responsibility for maintenance and body corporate representation.”

HouseMate participants would be required to occupy the house for seven years and subjected to limits on selling or renting it out later.

After the seven years, they could sell, but if it was to someone in the private market instead of to another eligible HouseMate participant, that would trigger a “waiting period” of seven years before the seller could buy another home in the scheme.

And a fee of 15 per cent of the sale price would be imposed, he proposed.

Creating cheaper homes

Right now, it takes a young couple seven years on average to scrape together a big enough deposit to buy their first home.

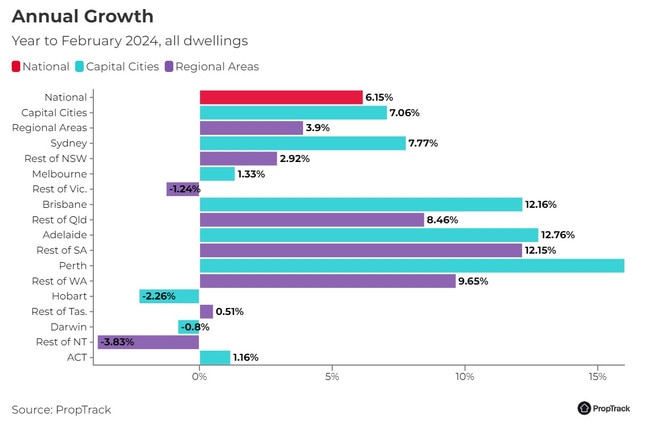

Median home prices are at record highs across the country – $1.89 million in Sydney, $1.24 million in Melbourne, $1.05 million in Brisbane, $956,000 in Perth, and $870,000 in Adelaide.

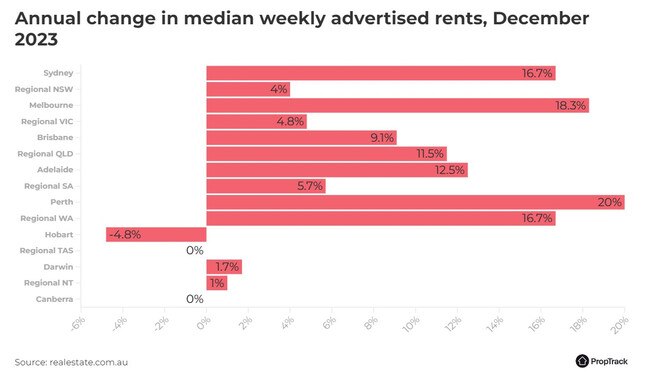

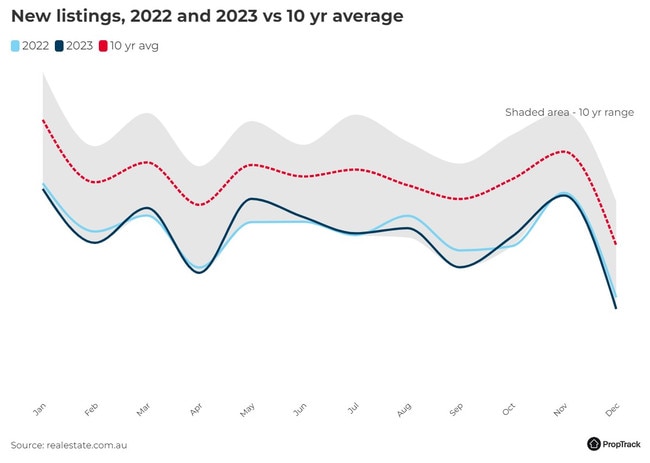

And the skyrocketing cost of rent, which has risen by double-digits in most capitals over the past year, but by as much as 30 per cent in some suburbs, makes saving even harder.

With a system like HouseMate, those dire figures wouldn’t matter much, Dr Murray argues.

Dr Murray argues that such a scheme would make the housing in the scheme cheaper – and not inflate prices, as most government support interventions in the past have tended to.

“My calculations suggest building these homes on land that would cost little – perhaps $50,000 averaged across all types – would by itself cut the price 20 per cent to 35 per cent,” he said.

“The lower interest rate, and the use of superannuation savings for both the deposit and repayments, would cut [the price further, and] the ‘after super’ cost saved by as much [as] 50 per cent to 70 per cent.”

Using superannuation savings for housing makes sense, where available, because homeownership does more for financial security in retirement than super alone.

“Because the use of super would be quarantined to new HouseMate homes, it would be unlikely to push up the price of existing homes.

“No other housing policy change would do anything like as much to make homeownership cheaper, or to free up income for families at the times they need it most.”

For example, axing generous taxation arrangements like negative gearing and capital gains tax discounts would push home prices down by about 10 per cent, Dr Murray calculates.

The HouseMate idea bares similarities to a revolutionary system successfully adopted by a nearby country more than six decades ago.

The Singapore model

If you hop on a plane and fly eight hours northwest from Australia, you’ll find a small but densely population island nation that seems to have figured out a solution to the housing problem.

Singapore’s population of 5.45 million people is roughly the same as Sydney’s resident base of 5.31 million people, and yet the country has virtually none of the housing woes that Australia’s biggest city does.

In 1960, in the lead-up to Singapore separating from Malaysia, the Housing and Development Board (HDB) was established to provide citizens with high-quality and affordable places to live.

Homes are issued by the state on 99-year leaseholds and values are based on size, dwelling type and location with financing provided by the government, as well as via Singapore’s version of superannuation.

The resale value of HDB homes diminishes over time as the lease period reduced, helping to prevent exorbitant price growth that undermine the merits of the system.

On top of that, the law prevents Singaporeans from owning more than two homes at a time.

Some 60 years later, Singapore’s HDB provides about 80 per cent of all homes in the country, Richard Reed from Deakin University said.

“Approximately 90% of households in Singapore own their own home and there are also grants for first-time buyers and second-time buyers,” Dr Reed wrote in The Conversation.

The model shows the importance of long-term thinking when it comes to solving social issues like housing, John Bryson, an expert in enterprise and competitiveness at the University of Birmingham wrote for The Conversation.

“In Singapore, [housing] is treated as an asset to the public purse, as well as a social asset – and carries no stigma, nor is seen as something to be avoided, if possible,” Professor Bryson said.

A big reason for that is how communities are designed, he explained.

“Singapore’s HDB housing units are built in HDB towns with housing units integrated with amenities including clinics, community facilities such as parks and sports facilities, and retail.

“As Singapore has developed economically, HDB has also begun to produce more up-market housing.”

Saving the Great Australian Dream

Home ownership rates in Australia have tumbled over the past several decades, with 67 per cent of Aussies owning the place they live in as of the 2021 Census.

That’s down from 70 per cent in the early 1970s, which doesn’t sound like a significant drop, but the declines are much greater across the age groups.

Those aged between 30 and 34 had a homeownership rate of 64 per cent in 1971, but it’s fallen by 14 per cent up to the 2021 Census, sitting at 50 per cent.

Half of younger Aussies aged 25 to 29 owned their own home in 1971 compared to just 36 per cent.

While the proportion of Aussies who own a home has fallen fall, Dr Murray points out that it’s surged in Singapore – from 60 per cent in 1971 to 80 per cent now.

If Australia was to adopt a system like HouseMate, it wouldn’t need to be at the detriment at the private market, he argued.

“Most people will still buy in the private market,” he said.

“When people talk about solving the housing issue, they miss the fact that if we make home prices and rents considerably cheaper, we’re screwing over the majority of Australians – the 66 per cent who own a home, and the 18 per cent who are landlords.

“I’m fine with that, but politically, you’ve got to accept that it’s not going to happen.

“So, why don’t we just leave that part alone – let it slide – and focus on renters, the ones who are really suffering.

“They’re the future homebuyers that we could offer a better option to, and therefore we’re kind of ‘solving’ the whole market.”

Aussies are ‘slaves’ to the economy

Enormous housing costs make people “slaves” to their jobs and the pursuit of unsustainable economic growth, Alex Baumann, a sessional lecturer in the School of Social Sciences and Psychology at Western Sydney University, said.

A model worth considering is the one found in Vienna in Austria, where major investments in public housing and rent price controls mean 80 per cent of residents spend only 20 per cent to 25 per cent of their incomes on housing.

Australia had a similar figure – the majority spending about 20 per cent of their income on rents, for example – a decade or so back.

These days, one-third of Aussies fork out between 30 per cent and 45 per cent of their money to lease a home, while a fifth have 46 per cent to 60 per cent chewed up by rent, research conducted last year by Statistica found.

The median rent for a home in Sydney is currently $1049 per week, while in Melbourne it’s $740 per week, in Brisbane it’s $716 per week, and in Adelaide it’s $638 per week.

Those prices have soared in recent times – up 12 per cent in Sydney and 15 per cent in Melbourne over the past year alone.

Vienna’s model shows that these stark figures don’t need to be an inevitability, Dr Baumann said.

“This policy redefines land and housing as social or common goods, rather than just as market commodities. After all, land, like air and water, is not a market good but part of our collective natural heritage.

“Such policies can significantly free people from economic growth reliance.”

Change takes time and effort

Should Australia choose to pursue a housing policy mirroring something like that in Singapore, it will take many years to achieve meaningful change, Dr Baumann conceded.

“The main barrier is inadequate funding of public housing,” he said.

“But as the housing crisis deepens, public housing is attracting more funding which could be applied to innovative housing models.

“The right model of public housing could eventually be expanded toward the high levels seen in places such as Vienna and Singapore.”

Of course, not everyone would want to live in public housing and a mix of dwelling tenure types will be needed.

“But widespread global adoption of public forms of housing could help balance the downsides of our current absolute reliance on economic growth.”

Transferring Singapore’s system to other nations with vastly larger populations would be difficult, Professor Bryson said.

“But perhaps there are lessons to be learnt regarding a longer-term approach to meeting housing need,” he said.

One is to adopt a more “integrated” way of thinking – a conversation that’s not about the number of homes provided and what they cost, “but a more sophisticated discussion [about] who that housing is aimed at, where it needs to be, and how it is designed to create a sense of place”.

“As important is the need to ensure housing is completely integrated into existing urban infrastructure, including roads, public transport, schools and health services,” he added.

Originally published as A leading economist has come up with a radical plan to end Australia’s housing woes once and for all