Pierre Bonnard tipped to become ‘household name’ in Australia

A French artist who is considered a “god” in Paris, and was admired by Monet and Matisse but critiqued by Picasso, is making a splash in Melbourne.

VWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from VWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It is Pierre Bonnard’s time to shine.

For too long the French painter, who was born in 1867 and died in 1947, has been unfairly overshadowed by Claude Monet and Henri Matisse.

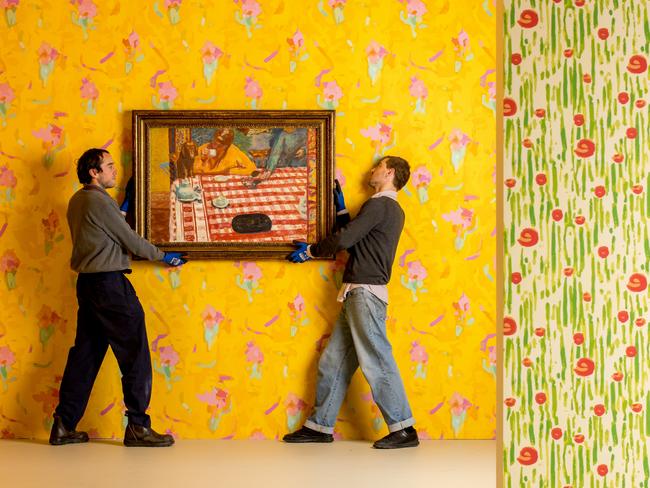

All of that is changing, with the Pierre Bonnard: Designed by India Mahdavi exhibition on at the National Gallery of Victoria.

The blockbuster Winter Masterpieces exhibition features more than 100 works by Bonnard – urban scenes, natural landscapes and intimate domestic interiors – alongside early cinema by the Lumiere brothers, and artworks by his contemporaries Maurice Denis, Felix Vallotton and Edouard Vuillard.

The icing on the cake is the Bonnard-inspired scenography by world-famous architect and designer India Mahdavi.

“In France, Bonnard is a god,” says Dr Ted Gott, senior curator of international art at the NGV. “I think he will go from being a lesser-known name in Australia to a household name after this show.”

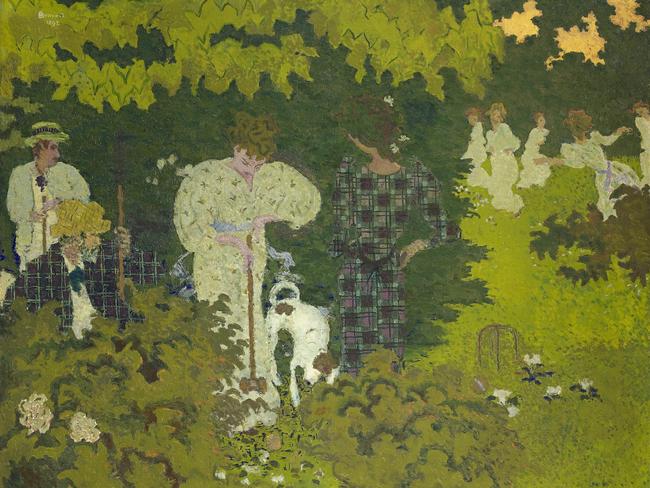

Bonnard’s career falls neatly into two parts. In his late teens he was part of the Nabis, a group of young painters who rejected Impressionism and were entranced by the flat styling of Japanese woodblock prints.

Something of a radical leftie, Bonnard was also part of the avant-garde theatre scene in Paris, designing the stage sets for the infamous 1896 production of Ubu Roi which set off a string of riots and was quickly banned.

“The Nabis created a new way of looking at the world,” Gott says. “They took painting away from being hung on a wall. The decoration element would become wallpaper or a dress or a fan or a street poster.

“They move from the reproduction of nature (as per Monet) to a flat design that leads aggressively toward abstraction. It takes oil painting to a whole new dimension. That is his great contribution to modern art.”

The Croquet Game (1892), which is on loan from the Musee d’Orsay and depicts the artist’s family playing in the park at Grand-Lemps, is an early Nabi-style masterpiece.

“It is one of my favourites,” Gott enthuses. “Bonnard’s sister-in-law, brother-in-law, and father-in-law are playing croquet on one side and in the background you have girls dancing.

“Everything is in this flat Japanese aesthetic – almost like it is cut out of crepe paper and stuck down like a jigsaw puzzle.”

By 1900, Bonnard starts to tread his own path. He is seven years into a relationship with lifetime partner and muse Marthe de Meligny and moves from a graphic to a more painterly style. The NGV’s Siesta (1900) is from this transition period – a languorous Marthe is draped across a mattress.

“Siesta is arguably Bonnard’s greatest nude but it is an unusual picture,” Gott says. “He is clearly looking at Renaissance art and at Titian … but he and Marthe are living in a rather squalid flat in Montmartre and you can see they don’t have a sheet and the mattress is just sitting on the floor. But in it is this glorious woman painted in a ravishing way with a gaze of love.”

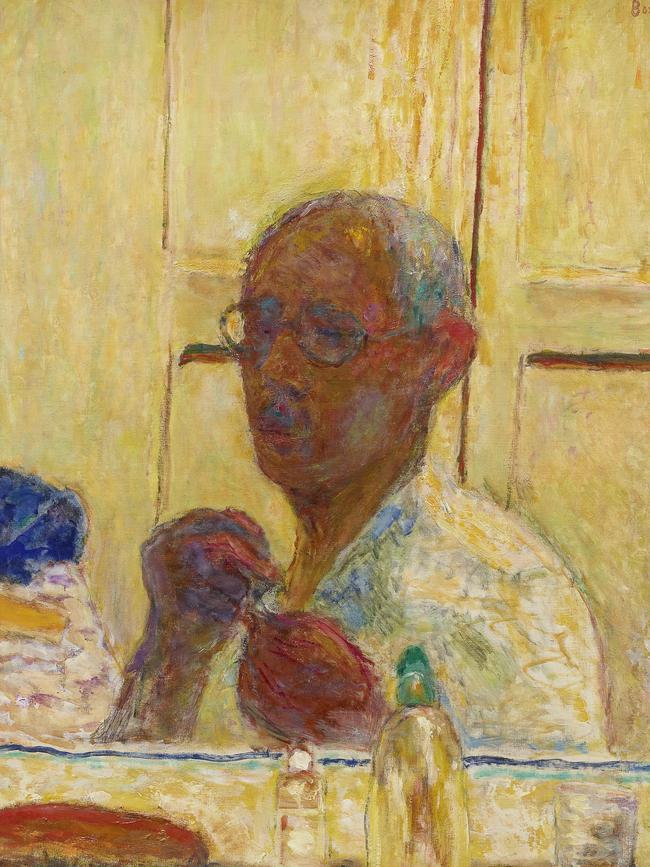

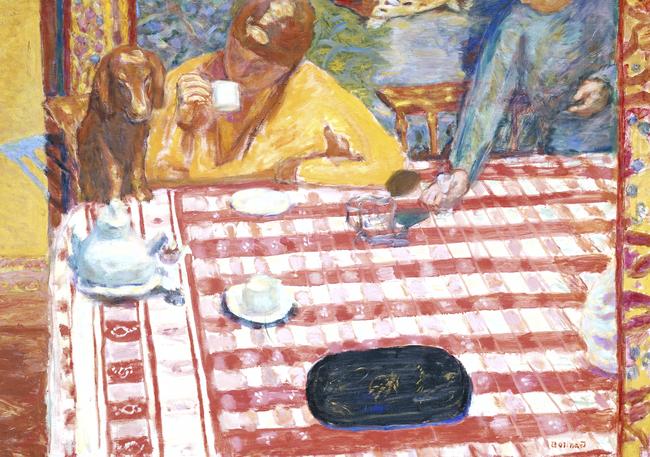

Bonnard’s mature style begins around 1910 and centres on radiant light-filled interiors depicting scenes of everyday life. Marthe, along with various pets is ever-present.

The Dining Room in the Country (1913), Coffee (1915), The Open Window, Yellow Wall (1919), White Interior (1932), Dining Area at Le Cannet (1932), and The Checkered Tablecloth (1939) are just some of the stunners on display.

“The paintings from 1910 to 1947 are incredible conglomerates. You have Marthe, the interior architecture, a view of the landscape, plus still life elements, and then you always have a little critter.

“They physically suck you in. You feel like you are almost floating into the pictures.

“Marthe stays ageless (throughout). Quite often her face is blurred or she is looking away. She is like a constant muse but they are not highly detailed portraits.”

Intimate images of bathing, including Nude with Blue Glove (1916) and Marthe Grooming Herself (1919) are another constant across the decades.

“(Bonnard’s nudes) are about invisible sensations – the aura of the body, the light on the skin,” Isabelle Cahn, emeritus senior curator of paintings, Musee d’Orsay says. “They are attractive and erotic.”

Bonnard straddles the eras of Monet (1840-1926) and Matisse (1869-1954) and he was friends with both.

“Bonnard knew Monet very well – his house in Normandy was very close to Giverny,” Cahn says. “Matisse was a big admirer of Bonnard. They corresponded. They exchanged letters.”

One detractor was Pablo Picasso who described Bonnard’s works as “a potpourri of indecision”.

“It was jealousy,” Gott says with a chuckle. “Picasso is about ideas and pushing the envelope. Bonnard’s sort of painting is sensuous and beautiful, slow and thoughtful.

“He is painting as though he is massaging a body. There is about ten things going on in each painting.

“You need time to allow your eyes to adjust and take in what you are looking at because they are so complex. In that sense he is amazing. He is not one artist. He is many artists.”

In his diary, Bonnard once expressed the hope that he should “like to appear to the young painters of the year 2000 with the wings of a butterfly”.

With Pierre Bonnard: Designed by India Mahdavi, that wish is about to come true.