Phiala Shanahan: Meet the brilliant, young Adelaide history maker unlocking the secrets of the universe

Phiala Shanahan is one of the most important young scientists on the planet. Here’s how she went from being a curious kid in Walkerville to the best in her field of physics.

VWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from VWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Growing up in Walkerville, Phiala Shanahan was a curious kid. Really, really curious.

She’d always want to know how things worked and why.

She’d do projects just for fun on weekends, everything from Ancient Greece to code breaking. She would read voraciously.

She would keep digging until she got somewhere. Until it started to make sense. Until she could start to paint a picture in her head.

Ultimately, the subject matter wasn’t really that important, it was the continuous and constant journey of exploration that drove her.

“I always wanted to understand everything about everything,” she says.

“And I was always very stubborn when it came to figuring out the answer.”

Mum Beate says her daughter was super organised and a born leader, who was naturally skilled at motivating people.

“She set up a shop when she was four years old,” she says.

“We were visiting family in Germany and there were these pine cones she collected.

“And she got all her cousins who were all older to paint them. For her. She was supervising and painting them.

“And then she sold them to the adults. She was very business-minded and had a very organised mind, all the time.”

These are just some of the traits which have served Professor Phiala Shanahan particularly well.

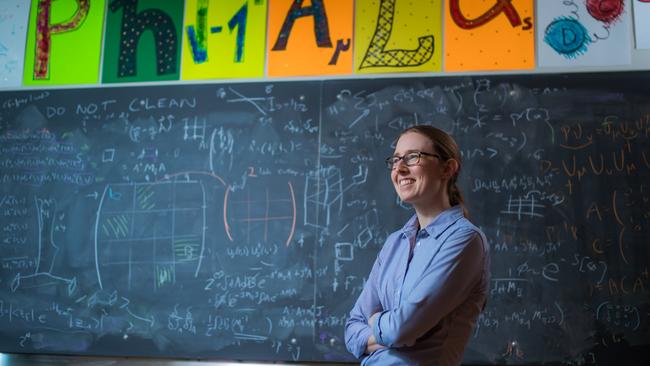

At 27 she was appointed the youngest Professor of Physics at the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Now, four years later, she is regarded as one of the most important young scientists on the planet, the best in the world in her chosen field, and has a job for life at MIT.

Smiling down a dodgy internet connection as we battle the Adelaide/Boston time zone difference, Shanahan, who in a day or so is off to Munich to speak at an international conference, recalls fondly her time growing up in Adelaide.

She beams while discussing the supportive teachers and her close group of friends at Wilderness School, the tight bonds with her mum, who still works at Ward’s Shoes in Norwood, and the nurturing environment at the University of Adelaide, particularly the mentorship of Professor Anthony Thomas AC, that opened her mind to the possibilities of a career in science and physics.

It’s a career choice she admits she came to rather late.

“During university, I was very much encouraged to study whatever I wanted to and not worry too much about where it was going,” she says. “And you know, if you love what you do, you’ll be able to make a career out of it.”

But she soon realised she had a knack for physics and was intrigued by some of the BIG questions. Questions like (but by no means exclusive to): Why are we here? What happened after the Big Bang? How much don’t we know? And how are we going to find that out?

She also thought that if she did well she might be able to realise a dream to live overseas for a few years.

Thomas described her as a “very driven” student who would push herself to the limits to get the results she wanted and would not tolerate failure, even if her version of failure was merely a mark or two below what she had aimed for.

But she also showed a lot of care for her fellow students.

“Phiala would regularly bake a cake on special occasions for people in my research centre; they were very good,” he says.

Once the penny dropped, her career really did (pardon the pun) hit the stratosphere.

Her CV is worthy of a stand-alone chapter (see graphic), but some of the highlights include the 2016 Bragg Gold Medal for the best PhD completion in physics in Australia and, the next year, being featured in the science category of Forbes Magazine’s 30 Under 30 (the same year she made history at MIT).

In 2020, she was named one of Science News’s 10 Scientists to Watch.

The same year, she received the Kenneth G Wilson Award for Excellence in Lattice Field Theory, MIT’s Teaching with Digital Technology Award, and an Early Career Research Award from the US Department of Energy.

But she reckons her greatest achievement was last year receiving tenure at MIT, one of the most highly ranked academic institutions in the world. A place that has, among other things, spawned 98 Nobel laureates, 26 Turing Award winners and eight Fields Medalists.

It’s her dream job and now one she can have for life. Every seven years she can take a 12-month sabbatical to do whatever she wants.

Tenure is normally offered to outstanding candidates, generally those who are world leaders in their field, after about seven years, having received endorsements from usually more than a dozen world experts.

Shanahan received hers after four.

She is the only South Australian woman to ever receive the honour in the Center for Theoretical Physics and one of only three Australians, the other two being Tracy Slatyer from the ACT and fellow Uni of Adelaide alumni William Detmold (another of Professor Thomas’ students).

“It’s permission to keep doing this job forever,” she says, smiling.

“It’s validation from the community … the department writes to all of the leading figures in your field and related fields and they ask, ‘So what do you think?’

“And all those leading figures have to say, ‘Yeah, I know who she is, she’s done great work. She’s the best in the world’ in some area.

“Knowing that all of those people made that judgment call on my work is very, very validating; it’s the ultimate prize because it’s both validation from the community and the permission to keep doing what I’ve had great fun doing for as long as I want to.”

It also means she can stay at MIT for as long as her heart desires.

Shanahan loved growing up in Adelaide.

However, in Boston, she found a place where she was simply meant to be.

“It’s the best job in the world. MIT is such an amazing place,” she says.

“It’s for me, it’s a place where I really feel like I belong, which wasn’t always the case growing up.

“I didn’t always feel like I fitted in with my classmates at school and university, and here I do. (In Adelaide) I had a close circle of friends and a really supportive family, and I was happy just doing my thing, but here it’s just different, everyone’s really passionate about what they’re doing.

“Everyone’s doing really exciting research. There are new ideas everywhere.”

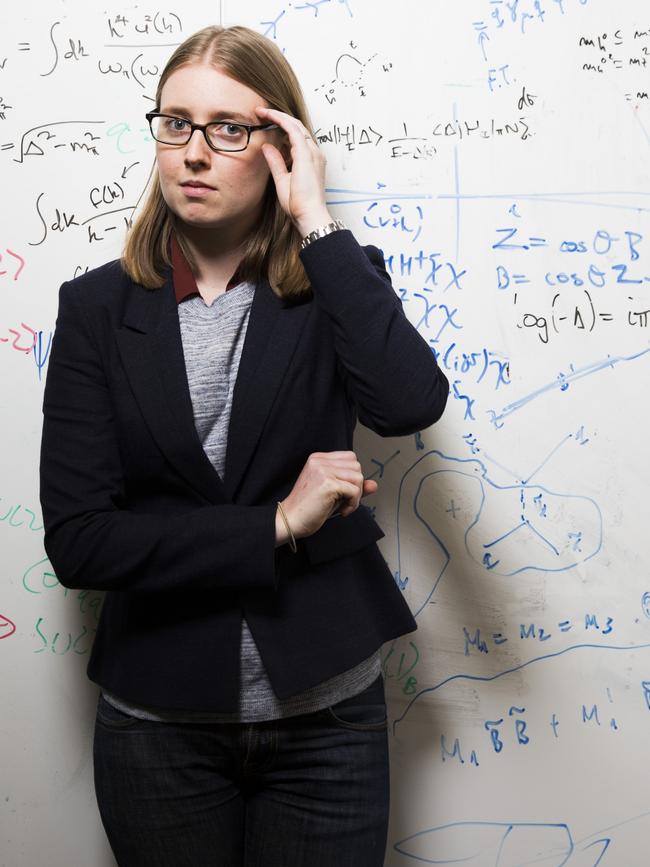

It would probably take a PhD to explain precisely what Professor Phiala Shanahan is doing with her work.

At worst it seems largely indecipherable, at best it sounds like the script of the next Marvel movie … especially when it starts talking about cool things like “dark matter”.

Suffice to say Shanahan is kind and patient when trying to spell it out to a career journo who failed general maths in Year 10.

Here goes …

As a theoretical physicist, her work focuses on one of the key scientific questions we’ve been asking since around 600BC: “What is everything made of?”

It’s centred on the fundamental forces of nature and the building blocks of the universe; stuff like matter, and protons, and neutrons, and gluons. (For those who were wondering, a gluon, according to britannica.com, is a messenger particle of the strong nuclear force, which binds particles known as quarks within the protons and neutrons of stable matter).

And it’s the job of a theoretical physicist to dissect the delicate balances that allow all of these universal building blocks to interact.

Shanahan challenges and tests long-held theories about how we have come to understand all these things (known as the Standard Model of particle physics … this will be a recurring theme).

“One of the big things I do as a theoretical physicist is develop new ways that we can study the theory of Nature that we have, to find where it breaks down,” she says.

“And, you know, try to find, firstly, the corners of our understanding where our theory doesn’t quite match what we observed about the universe, and then secondly, to try to explain them.”

The more we test and challenge these, the more we learn, she says.

“You have a theory and then you do some experiments to test that theory, and you find where the theory breaks down,” Shanahan says. “And then you try to come up with a better theory that better explains the universe we live in.”

The more Shanahan has done this, the more she has realised the Standard Model, as brilliant and elegant and fundamental to all future research as it is, doesn’t explain everything.

Like what is dark matter? (See breakout).

“Our understanding does not quite match what we observe about the universe,” she says.

“And understanding that will hopefully lead us to answers like, what is dark matter or dark energy?

“We really don’t know a lot about the answers to some of these big questions.

“How do they fit into the whole picture?”

The pay-off from answering such “big questions” is potentially immense.

It could mean new sources of energy. It could mean a far deeper understanding of the beginning of the universe. It will hopefully improve our responses to questions which have been bugging scientists for decades, such as what are the details of the nuclear reactions that power the sun, and those that happened in the very first seconds after the Big Bang?

More than likely it will offer opportunities that haven’t even yet entered our collective consciousness.

“Hopefully, we’ll find something that points us towards the new and unknown physics in the universe, so that we have a new Standard Model to understand even more of the universal structure,” she says.

Putting all this into practice is equally challenging and involves the small matter of changing how we use Artificial Intelligence (AI).

There are gasps from the audience at a public lecture in Ontario, Canada, when Shanahan talks about how tough it can be to test a whole lot of theory around the “What is everything made of?” type questions.

One equation involving protons would take a “fairly good laptop” 10,000 years to compute.

Not very practical, she admits, with a shrug of the shoulders.

So instead, we have super computers, such as “Summit”, which is housed in the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee.

That computer can do in one second what it would take the entire population of the world a year to do if everyone did one calculation every second for the entirety of that year.

But, again, these supercomputers are super expensive and, even then, won’t work fast enough to answer the questions Shanahan wants answered. At least in her lifetime.

So Shanahan decided to go down a different path, using artificial intelligence and machine learning to speed up the process.

AI has generally been used to mimic human intelligence. Shanahan has inverted the concept somewhat to use it to make calculations tractable that were previously thought impossible.

“Right now I’m very excited about trying to break through some computational barriers that are stopping us from doing fundamental physics calculations that we’d really like to do,” she says. “That involves a lot of algorithm development.

“I never imagined myself as someone who would develop algorithms. I always thought I’d be a pen and paper physicist, which I am, but now I also work with computers and lately spend a lot of time developing new machine learning tools.

“Which is something that I’ve really built from the ground up in the last three or four years.”

So much so that in this specific field (using artificial intelligence and machine learning to study nuclear physics from the Standard Model) Shanahan is regarded as the best in the world.

The next stage is her involvement in the launch of National Science Foundation’s Institute for Artificial Intelligence in the wider Boston area, which involves researchers from her team and others at MIT, Harvard, Northeastern and Tufts universities.

They’re developing the new field of “ab-initio AI”, which in essence seeks to create faster algorithms which can then be fed into supercomputers which are still being built, They’ll compute a billion billion (sometimes known as quintillion) operations each second.

“Machine learning has been wildly successful in domains like image recognition; for example Google can tell you if your photo is of a dog or a cat,” she says by way of simplification.

“I, of course, don’t want to know if my photo is a dog or a cat, I want to study the Standard Model.

“And so developing new tools in machine learning and artificial intelligence adapted to these precise physics questions, and to the scale of these massive computations, is a great task.”

There are clearly other factors driving Professor Phiala Shanahan.

Beate Shanahan says her daughter felt the death of her father, Terry, from cancer very deeply when she was aged nine.

“That was a very tough time and she totally changed, she became quite a quiet little girl. (Before) she was full of life and extroverted,” she says.

“They had a great relationship. It affected her very much.”

But it also drove her. Beate remembers they were worried about how they would pay the Wilderness school fees when Terry passed.

“She said, ‘Don’t worry, Mum, I’ll just get a scholarship,’” Beate says.

She sat for a few, was offered them all, and then asked Wilderness to match it.

They did.

Thomas remembers her still dealing with the loss when she worked as a summer student for him at the end of her second year at university.

She used it as a motivating force to help others. To problem solve.

“It is typical of her character that as a result she trained as a JP (Justice of the Peace) and spent time visiting people near the end of their lives so that she could not only comfort them but sign documents for them if needed,” he says.

He also recalls that she was an “excellent” saxophone player and “for some time her group used money earned in their gigs to support a charity that Phiala operated for a group of women in Africa”.

Professor Thomas is a much revered figure at the University of Adelaide, an AC recipient for services to scientific education and research and work that is internationally renowned.

He is not disposed to hyperbole and has what you could say is an almost fatherly affection for his many and varied students.

But in Phiala Shanahan he has clearly seen something a little special.

“If you add to this her scientific expertise and achievements, it is pretty clear that Phiala is a remarkable young woman,” he says.

“I have a number of past students who are in key positions in defence, industry, national laboratories and major universities around the world and as they all have their strengths it is difficult to compare, but there is no doubt that Phiala is one of the most outstanding.”

William Detmold, her fellow Adelaidean and colleague at MIT, concurs.

“Phiala is a great colleague who has discovered remarkable new aspects of physics and I am sure she will make a host of new discoveries in the coming years. I am excited to see what new insights she finds,” he says.

“The MIT Physics Department is ranked amongst the best physics departments in the world and Phiala is the youngest tenured professor on our faculty.

“Her rapid evolution from an undergraduate student in Adelaide to a leading member of the physics academy is both impressive and remarkably well-deserved.

“Her career path and incredible success should be an inspiration to the next generation of students in Adelaide and around the world.”

Beate, meanwhile, is simply rapt to see her daughter happy. “She could go into industry, she could be in the CIA somewhere, anything you want,” she says.

“She could earn lots and lots of money. And that is not what she wants. She wants exactly to do what she’s doing. I’m very happy about that.”

Phiala Shanahan does rock climbing to relax and recently returned from a trip to Utah.She likes to stay active, set up a home gym during Covid-19, and also enjoys mountaineering and martial arts (she’s a Black Belt in taekwondo). She loves the outdoors and was in the Boy Scouts when she was young.

“I was the first girl in my local Boy Scouts because I loved the opportunity to get outdoors,” she says.

She still has musical instruments lying around her Boston apartment and picks them up whenever she feels the need.

It’s clear she is doing pretty much exactly what she wants even though, for a long time, she didn’t really have a clear plan.

It’s a message she’s keen to share to the young Aussies who reach out to her for advice most weeks, or the students she teaches day-in, day-out as part of her role at MIT.

“Follow what you’re interested in,” she says without pausing.

“And don’t necessarily worry too much too early about whether there’s a clear plan for where your career is going to go.

“Focus on really understanding things, really, digging in deep and following something you’re passionate about.”

Beyond this, she is keen to see a higher value being placed on science, particularly at a time when studies show an under-representation of women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths) jobs. “At the most fundamental level, science is thinking about the world in a particular way, and using logic to understand the universe,” she says.

“And I think that is so, so valuable, especially for our young people, no matter what careers they go into.

“Having a science-based education helps you interpret the media. It helps you think about how the universe works, which is important for everyone, no matter what they do. And I think that often gets lost.”

For this, governments also have a significant role to play, Shanahan says.

“It’s hard to get grants in Australia for basic science. Often you have to justify them by saying, ‘Well, there’s going to be some industry application or I’m training people to go into codebreaking,’” she says.

“There has to be something extra beyond science for the sake of understanding the world.

“But by-product of blue-skies research are people who are trained to really think scientifically, and problem solve, and that is also important to society in its own right, and not just because of a potential direct industry benefit.

“It is a valuable background, whether our students go into fields like medical research or energy research, or even if they go off and become a lawyer.”

Our internet connection is just about ready to pack it in and Phiala Shanahan needs to start getting ready for her trip to Munich.

After a few final pleasantries, the interview closes off with, “What’s one scientific question keeping you up at night?”

She pauses for a second. Then answers.

“Maybe how the Standard Model and gravity fit together. Yep, that’s one of the big ones.”

This journalist’s Year 10 general maths module didn’t extend to physics, and Standard Models, or even gravity, but one has the distinct impression that, whatever that means, Professor Phiala Shanahan – scientist, teacher, innovator, collaborator, problem solver, rock climber, martial arts expert and sax player – won’t die wondering.

Originally published as Phiala Shanahan: Meet the brilliant, young Adelaide history maker unlocking the secrets of the universe