Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre celebrates 75 years of lifesaving research, treatment

The Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre will celebrate 75 years this year. In that time it has been the home of many lifesaving medical breakthroughs, as researchers continue searching for cancer cures.

VWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from VWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

If one word best describes the journey the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre has been on over 75 years, it’s that which once no one would dare whisper and now is part of the daily vocabulary: Cure.

“When I started here in 1993 everyone would be very reticent to use the word cure,” surgeon and former Peter Mac chief medical officer David Speakman says.

“In the history of Peter Mac we’ve gone from never using that word to using it daily.”

But for a hospital that can lay claim to any number of medical discoveries and lifesaving breakthroughs, it says much about the Peter Mac that what it celebrates most is connection to community.

Dr Speakman — a specialist in melanoma (a type of skin cancer) and breast cancer — was chief medical officer at the Peter Mac for a decade from 2013 and says the advances made at Australia’s only public hospital dedicated to cancer have been “incredible”.

“One of its greatest achievements is being able to get what happens in the lab, into the clinic and then for that to spread across Melbourne, Victoria, Australia and wherever else.”

BREAKTHROUGHS

Its celebrated breakthroughs span the spectrum from inventing, refining and testing new treatments to tackling the big “how” and “why” questions of cancer which, put simply, are cells gone rogue and are multiplying out-of-control.

Peter Mac’s contributions include:

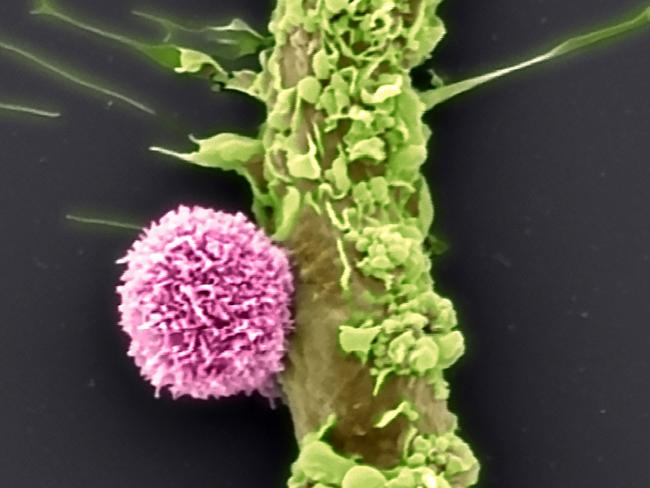

MELANOMA: helping increase five-year survival rates to more than 90 per cent by staging pivotal clinical trials for the latest immunotherapies which harness the patient’s own immune system to fight cancer.

BREAST CANCER: Home to some of the world’s leading researchers, particularly in the more aggressive types of triple negative and HER2-positive breast cancer, who are changing how this cancer is understood and treated globally.

This includes new ways to predict how patients will respond to treatments – or potentially avoid debilitating chemotherapy. They have also developed an online tool to help women assess their breast cancer risk called iPrevent, and led the work in how hormone positive disease is treated in young women around the world.

BLOOD CANCER: Australia’s leading site for CAR T-cell therapy, which involves collecting the patient’s T-cells and re-engineering these so they can fight their cancer. Already a breakthrough in treating “liquid” blood cancers, scientists – including at Peter Mac – are also working to apply this treatment to “solid” tumours like breast cancer.

CAR T-cell therapy is now changing lives, in particular children and young people with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and adults with diffuse large B cell lymphoma.

PROSTATE CANCER: Peter Mac is driving development of a new type of targeted radioactive treatment called Lutetium-PSMA and was the first to introduce public robotic prostate surgery that is now also regularly used to treat prostate and other cancers.

“The importance of having robotic surgery available in the public health system to give everyone access to the best care shouldn’t be underestimated,” Speakman says.

HEAD AND NECK, UROLOGICAL AND GYNAECOLOGICAL CANCERS: Surgery for cancers in hard-to-get-at places, where conventional surgery can be very debilitating, has become minimally invasive because of robotic surgery. It has fewer side effects, less damage to the patients and better outcomes. Also, Peter Mac’s “Gamma Knife” – the first installed in Victoria and only third in Australia – performs non-invasive radio surgery in parts of the brain off limits to conventional surgery.

PANCREATIC CANCER: immunotherapy and precision medicine – including a highly powered and targeted type of radiotherapy called SABR – is improving outcomes where once there was little hope. Treatment options have also been improved by artificial intelligence (AI) and computational informatics. A next-gen approach is investigating an RNA-based therapy seeking to stop this hard-to-treat cancer in its tracks.

LUNG CANCER: survival rates have tripled. Speakman says about 35 per cent of people who walk in the door of the Peter Mac now have their lung cancer “type” identified by DNA.

“We find the gene of the genetic defect that’s driving the cancer and then we have a drug that will turn that gene off, or block a pathway that’s helping that cancer to grow,” he says.

Speakman says lung cancer screening, while in its infancy, will be crucial in future.

“Kudos to the federal government that we’re now well down the path to that happening, because that’ll drive us from finding late stage cancers to finding them earlier with much better chances of things like surgery or radiotherapy treating another block of patients and getting great survival.”

OVARIAN CANCER: while still looking for the holy grail of early detection, Peter Mac is working across the Parkville precinct with hospitals such as The Women’s and institutes including the WEHI to find lifesaving answers.

“We’ve found some targets, borrowed drugs out of other areas that are now targeted for ovarian cancer,” Speakman says.

Early detection will be key and PET scanning may hold the answers.

“That, along with the technology improvements in both MRI scanning and CT scanning, have helped us improve outcomes for patients.”

CAREER IN CANCER

Speakman was headed for a career in vascular surgery until a mentor suggested he visit the Peter Mac and speak to respected breast cancer clinician Michael Henderson.

“When I came to the Peter McCallum what I found was a place where everyone in the building was focused on the patient and on doing their very best for that individual patient in front of them,” Speakman says.

“When you come to a place like that, and that’s the vibe, it’s pretty hard to escape.”

He joined the melanoma unit and it had a profound impact.

“In the first couple of months I met a young woman who was 19 and had a melanoma on her back. She didn’t see her 21st birthday,” he says.

“In my time at Peter Mac, I’ve seen that scenario change from total devastation, you know, her losing her life, her family being devastated, to fast forward to 2024 when most patients who walk through the doors of this institution with melanoma will be, if not cured, at the very least kept alive for years to see their kids grow up, to see their grandkids grow up, to live as long and as productive a life as we can give them.”

This weekend marks the 75th anniversary of the Peter Mac board’s first meeting, held on April 27, 1949.

From modest beginnings in a single room in the old Queen Victoria Hospital on William St, the Peter Mac – named after respected Victorian researcher and pathologist Sir Peter MacCallum – is today modern and streamlined; a diamond in the Parkville research precinct.

“We’re incredibly lucky to be in a wonderful building, which to be honest is really about a better patient experience,” Speakman says.

“But it symbolises where we’re going, and the changes and the improvements in cancer care are literally exponential.”

As Australia’s only public hospital dedicated to cancer, it treats more than 42,000 patients a year.

The work of its 700 scientists now regularly make the pages of top scientific journals and their key discoveries have helped to revolutionise cancer care. Thanks to them, cancer for many patients in 2024 is a manageable, if not curable condition.

The future is also in good hands.

LIQUID GOLD

Dineika Chandrananda was destined for a career in academia and an opportunity to work in cancer research at the Peter Mac brought her back to Melbourne five years ago.

Now the Peter Mac is the young researcher’s “forever home”.

Her work is set to not only revolutionise the way patients have biopsies, but if clinical trials are successful, perform them almost pain-free.

“I work with something called liquid biopsies,” Chandrananda says.

“The standard practice for biopsies now involves a big needle. It is inserted deep into the body to get a sample of the tumour cells, and anyone who has done a tissue biopsy will say it’s a very painful procedure with a lot of anxiety involved.”

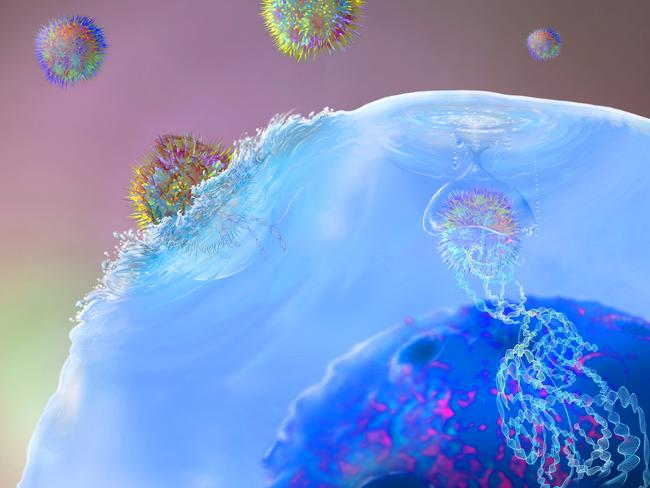

Her work centres on proving that liquid biopsies can accurately identify circulating tumour DNA in patients.

“These are small chopped up pieces of DNA that are released by tumour cells into a patient’s bloodstream,” she says.

“We essentially can get access to these circulating DNA fragments that are from the tumour and stitch them together to get an understanding of the cancer.

“It is a blood test so there is no need to insert thick needles anywhere. That’s why it’s called a liquid biopsy.”

They offer the potential of a future road map to more quickly identify the presence and type of cancer, and how a patient will respond to treatment, from blood tests.

Chandrananda warns there are limitations to be worked through before this becomes standard practice in clinics, but that AI is helping to move things at pace.

She explains that DNA is essentially a big collection of data with three billion locations that can be altered in a cancer patient.

“At the Peter Mac we have built tools to pull as much information as possible from each liquid biopsy, to give a more complete picture of a patient’s cancer overall,” she says.

“If there’s mutation in a certain location, we try to capture it and then we try to see, does this mutation make the cancer grow faster, or does it allow the cancer to hide from the immune cells of the patient? Is a gene switched off or on, and what do these genes do?

“We get an understanding of the biology of the cancer.

“This is not a hypothesis we are testing, it is actual patient data and you can clearly see how liquid biopsies will benefit the clinic.”

That’s what brought her to the world-renowned hospital with its unique environment that integrates research, education, and clinical care.

“Before I came to the Peter Mac I never had the chance to work as closely with patients,” Chandrananda says.

“I didn’t get to hear their stories. I didn’t get their input in my research. Now my motivation is just so much different.”

NEXT STEPS

So, is there a cure for cancer?

“We’re getting better at detecting, we’re getting better at treating, but we can still improve screening rates in the community to help us prevent more deaths,” Speakman says.

He says a different approach is needed and that may well come in the form of targeted vaccines to stop particular cancers. These are being worked on now, using the same mRNA technology developed during Covid.

“I think a silver bullet to cure all cancer is probably not going to come in our lifetimes,” Speakman says.

“We’ve been looking for it for a long time, and it probably is not one silver bullet, but we’re getting a lot better at having the right bullets aimed at the right place.

“If I had to tell you in one sentence what’s happened in the last 25 years in cancer care, we’ve gone from approaching cancer with a shotgun, and just shooting at everything, to having sniper bullets hitting exactly what we want and knocking it out at the first go.

“I have hope, great hope. We’re changing the way we approach cancers every day of the week, which is fantastic.”

COMMUNITY

Over the click-clacking of knitting needles there’s laughter coming from the Kurunjang Community Hall near Melton.

It’s the weekly meeting of the CommuKnitty Crafters group, started during Covid by Melton City Council to keep senior members of the community connected.

“Volunteering is something I had wanted to do since I retired,” Sandra McMenemie, 68, says.

She’s the youngest of the core group of five who now knit for the Peter Mac. The items they create are more about raising spirits than money; a way to show patients they care.

In the local community hall these women weave a little magic making bright blankets, knitted beanies and soft scarfs.

“We started with blankets, but it gets a wee bit tedious and hot so we got in touch with the volunteers at Peter Mac and they suggested beanies and scarfs,” McMenemie says.

“Patients going through chemo feel the cold.”

The women now regularly deliver “boot loads” of knitted items, with most given free to patients.

To the Peter Mac, this small group of women represent the heart of community.

“It sort of invigorates you again that people do need this kind of stuff,” McMenemie says.

“When something you have made puts a smile on someone’s face, that makes us feel happy.

“To think that we can contribute to something like that is incredible.”

The Peter Mac team say that the knitted items are handmade and that makes them more powerful and meaningful to patients who have cancer.