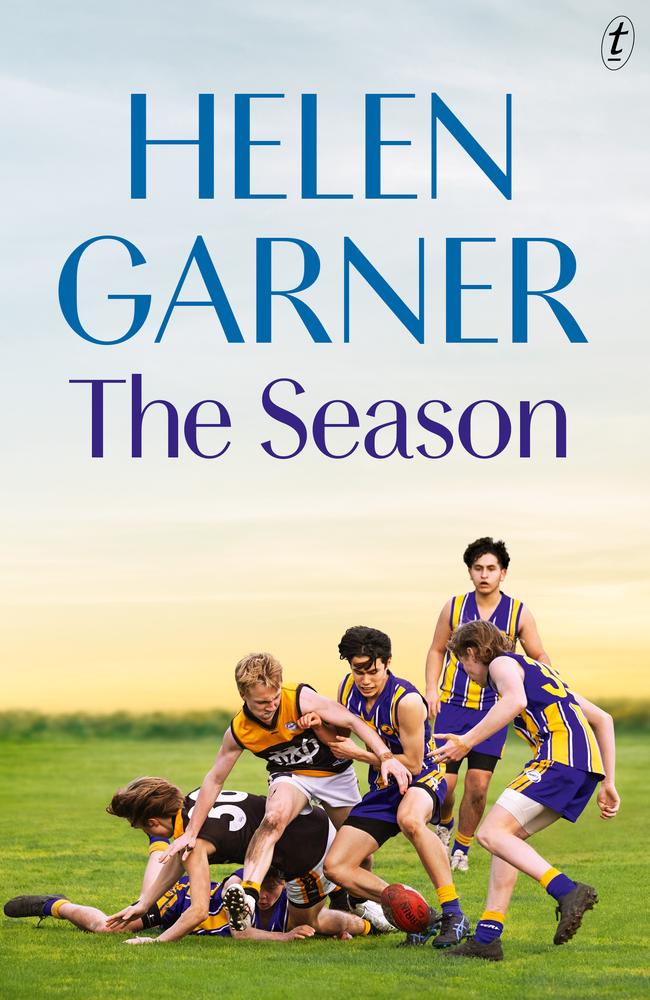

‘I want to know him better before it’s too late’: Helen Garner on the boy who inspired her new book

Cherished Australian writer Helen Garner thought she had written her last book, until her grandson lured her out of writing retirement. Read the exclusive first extract of the book he inspired.

VWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from VWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Helen Garner thought she was done with writing. But wanting to be closer to her youngest grandson meant footy, boys at dusk, the world of tackles, goals, sirens and grazes. Boys becoming men. And another book.

Extract

I need a reason to be near my youngest grandson, in the last years of his childhood. I want to know him better before it’s too late, to learn what’s in his head, what drives him; to see what he’s like when he’s out in the world, when he’s away from his family, which I am part of; so in order to learn about his other life, I’m going to have to find a way to efface myself, to become a silent witness.

Footy is his other life. He plays in our suburban Under-16s AFL team. He can’t imagine why I’m suddenly interested, but he gives me permission to come not just to his matches, but to twice-weekly training.

I thought I was done with writing, that my working life was over. But here’s my chance: maybe I can write about footy and my grandson and me. About boys at dusk. A little life-hymn. A poem. A record of a season we’re spending together before he turns into a man and I die.

An hour before we leave for Amby’s first real match of the season, I’m scraping shit out of the chooks’ roosting box and notice him bent over, studying something on the bricks near the clothesline.

“What is it?”

“A wasp and a bee, fighting.”

I approach. The wasp flies away. We remain bent. I confess that I wouldn’t know a wasp from a hole in the ground.

“They’re more brightly coloured than bees.”

The wasp, on its erratic flight path, returns to the scene of the crime. We bend lower.

“Oh yes. I can see its stripes. Sheet, it’s really murdering that bee.”

The bee is moving feebly, trying to wriggle away, but the wasp is heavier and stronger, violently in command.

“Is that what it’s like to get tackled?”

“No,” he says. “It’s not like getting stung to death.”

On the drive west to Sunshine for the game, Amby in the back seat is silent and rather pale – tall and powerful, broad shoulders, long bare legs. Many of the houses we pass, with their pastel asbestos walls, messy yards and gateless entries, feel familiar to me.

“I like it out here. It reminds me of Ocean Grove.” It’s “the past” that it’s reminding me of, my childhood, the 1940s and 50s. At a railway crossing we pause beside a deserted house that’s partly obscured by a sign advertising the large, grey apartments that will be built on its site. The side of the doomed house is painfully appealing to me. Shrubbery presses close to its window, old bricks lie about, a rusty barrel; its driveway is tyre-flattened mud with traces of green. What am I doing out here? What will I say if someone asks me? “I’m with the Colts. I’m their witness.”

And here they are, the Colts U16s, playing a constricted kick to kick in a small concrete yard beside the Sunshine clubhouse, all in their team jumpers, clean and ready, their hair shampooed, their faces shining but purposefully blank. I am not used to seeing them in full daylight. How young they look, how smooth, unlined! They have men’s voices but boys’ faces. Xavier has cut off his low ponytail. Aiden’s long mullet flows down the back of his neck in a glistening curve, as if blow-dried. Archie, their young coach, strides up to them with a folder against his chest, his cap on backwards, white-cheeked but smiling.

I find a space on the boundary fence, near a woman with a tiny black poodle on an extendable lead. Small boys pass in pairs, always one holding a ball, their heads together in solemn conference. The oval is in good nick; it’s got that slightly domed shape that makes you feel you can see the curve of the planet.

I hear a burst of cleats on the concrete behind me and turn in time to see the Colts form a line and stride towards the ground. Our boys. My God, they are men, in their vertical stripes and white shorts, even the little skinny ones are men: it’s the groupness of them that makes them men, moving with purpose in a thick bloc. Why do I feel like crying?

The siren, the bounce, boys explode in all directions and I’m lost. Amby’s dad is standing near me, following with his experienced gaze, making comments, letting out the odd cheer or groan, but I’m in a panic. The ground is too enormous, I’m too small, my eyes are no good, I can’t recognise anyone or understand what’s happening. I need TV, give me TV – the edited and packaged version of the match with its roving cameras and close-ups and aerial shots, and commentators pouring out names and manoeuvres and opinions, the voices that know everything – I am totally dependent on them.

Oh it’s hopeless, and I can’t pretend that my eye is not always seeking out Amby. I try to force myself to survey the game in a detached spirit, but I know the shape of his shoulders, the angle of his run, and there he goes, breaking out of a pack, holding the ball forward and low, running in long strides, getting his boot to it and sending it sailing down the wing.

At quarter time I slink out on to the ground behind the coach. I want to hear his commanding voice, someone to pull it together for me, the spectacle of what the hell I’ve been straining to see. The boys, panting, press shoulder to shoulder before him. Amby is right at the back. His face shocks me, darkly flushed, open-mouthed, glistening with sweat: what I see is a man.

“If you take a mark,” says Archie, “don’t just bomb it in! They’ll mark it! That’s what they want us to do! Let’s have a bit of composure! Take your time!”

Angus, minus his earring, is standing to the right of the coach and behind him, looking into the distance – is he even listening? “Come in front, Angus – come in front.” The boy obeys, reluctantly. Is something biting him?

Archie’s clear, strong voice: “Tackling – there’s too much of this patting!” He mimics it, whacking his flat palms pointlessly all over the nearest boy’s chest and shoulders. “You’ve got to go for their hips! And bring ’em down! Also, I see people walking! Are they walking? If I see anyone walking with their head down, sad because they didn’t get a goal – that’s bullshit! Never be walking! We’re five goals down but we can win this! We’re a better team than they are. They’re winning because they’re working harder.” They are?

The siren sounds and I try to watch analytically instead of gazing in a trance. And Archie’s right. Sunshine are going harder, they’re heavier and faster and more determined in the contests. Some of the Colts seem to me to be holding back at crucial moments. Are they scared? Of getting hurt? Who wouldn’t be?

“At least compete,” mutters Amby’s dad. “We’re not competing in the air – we’re not flying with any conviction for the ball!”

Archie turns away from the field with a pant of frustration, pressing his fists into his eyes. They’re all over us, kicking goal after goal. And yet some of the Colts, even I can see, keep throwing themselves into it with everything they’ve got. They get the ball up to our forward line and that’s where it all falls apart. I dimly grasp that this is why we’re losing; and after the final siren it’s what everyone around me is saying, so maybe I’m not as clueless as I think.

Amby in the car home is given the front passenger seat, the place of honour. He is very quiet. He has a six-inch bloody graze on each elbow. His dad praises his playing. The praise is sincere, and deserved: he played bravely, and skilfully, he didn’t let up. They begin to analyse the game, side-by-side in the front. I lean forward but the radio is on loud, tuned to another game, and drowns out what they’re saying. I feel old and deaf and awed, in the back seat with the dog.

The next night, after dinner, the table strewn with picked bones, Amby’s dad comes out with memories of his own youthful footy years. They compare notes on tagging.

“One time,” he says, “this bloke was tagging me and he kept pinching me, you know? How they get at this bit of skin round your waist? And pinch you?”

What? They pinch you? Isn’t pinching sort of girly? Is it allowed?

“And finally,” he says, “I just lost it. I swung my arm right round, like this, and I smashed him. And then I smashed him again. I was reported. But he never pinched me after that. Don’t get me wrong – I’m not in favour of violence, but –”

Amby leans forward: “But I feel like that all the time. And I don’t just mean in footy, either. I really want to –” He grits his teeth, thrusts out both arms and mimes punching and throttling.

We’re all laughing, but nervously. I suppose they’d talk differently if I wasn’t here.

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘I want to know him better before it’s too late’: Helen Garner on the boy who inspired her new book