Dan Liebke reveals the funniest moments in Aussie cricket

From madcap pursuits, comic foolishness and sheer audacity, these are some of the 100 funniest moments of all time in Australian cricket.

VWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from VWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Most of the time you don’t think of Dennis Lillee as funny. I mean, sure, to modern eyes, there’s something vaguely preposterous about many of the cricketers of the 1970s. Their machismo, heavy drinking and general roughness make them seem like stereotypical Australians, characters straight from Monty Python’s Bruces sketch, except less nuanced.

Most of the time you don’t think of Dennis Lillee as funny. I mean, sure, to modern eyes, there’s something vaguely preposterous about many of the cricketers of the 1970s. Their machismo, heavy drinking and general roughness make them seem like stereotypical Australians, characters straight from Monty Python’s Bruces sketch, except less nuanced.

Dennis Lillee came up with a lot of comical foolishness above and beyond the general baseline of 1970s macho nonsense, standing out as a man capable of ridiculousness even among his ridiculous peers.

Probably the best example of Lillee’s weirdness was the time he asked Queen Elizabeth II for her autograph. Does one ask royalty for autographs? No.

The incident occurred during the Centenary Test, a one-off match between Australia and England held in 1977 at the MCG to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the very first Test. On the final day of the Test, the contest was approaching a thrilling climax. (Thrilling, but also repetitive, as the game would finish with the same result as that original Test, an Australia win by 45 runs.)

With just one session remaining, Queen Elizabeth II popped by to meet the players. Australian captain Ian Chappell introduced her to his team, eventually reaching Lillee, who, seizing the moment, requested an autograph.

Why not? Maybe she’d sign his bat or something.

Alas, no. The Queen turned him down. Worth a shot, though. Let’s hope Cameron Green has better luck with King Charles in the 2027 Sesquicentenary Test.

Shane Warne’s last-ball mind games chat

There were many extraordinary facets to Shane Warne’s bowling.

One of the greatest aspects of Warne’s bowling, however, had nothing to do with his capacity to roll his arm over and hurl a spinning cricket ball down the pitch.

I refer, of course, to Warne’s mind games. His ability to get inside the head of a batter. Or an umpire. Or his teammates. Or the crowd. Or any combination of those.

Warne could, by sheer force of personality and reputation, make people believe in the existence of the most non-existent things. And no moment better exemplifies this than the last ball of the third day of the third Test against Pakistan in 1995.

That’s when Warne, and long-time co-conspirator Ian Healy, came together for a chat before the final ball was due to be delivered. Being the last delivery of the day, there was no rush. Warne could take his time, prepare his schemes, consult with his keeper about how best they might deceive the batter and trick him into ...

No, I’m hearing that instead Warne and Healy had a quick discussion about where they might go out for dinner after the day’s play, before Healy trotted back to his position behind the stumps.

Not that anybody other than Warne and Healy knew that. For all the world, it looked as if the pair were scheming up a storm. A couple of Ocean’s Elevens, not even bothering to get the other nine involved.

For batter Basit Ali, their conspiratorial craftiness had him on high alert.

All he had to do, however, was get through one final ball. He’d already survived an hour in the middle, facing 58 deliveries. One more should be within his abilities, no matter what line of attack Warne chose to probe.

He would brace himself for the delivery and throw everything he had into defending it.

All these thoughts flowed through Basit Ali’s brain, engaged in furious Dune-like battle with the mind worms Warne had inflicted upon him through nothing more than a mysterious conversation at the top of his mark.

And then, perhaps inevitably, Warne bowled him.

The mind games had worked. Warne had claimed another victim in dramatic, hilarious fashion, thanks primarily to the power of his mind.

Well, the power of his mind, plus a sharp-turning ball out of the rough that somehow turned between the batter’s legs to crash into leg stump.

If you’re going to muck about with mind games, it definitely helps if you can also pull off the most preposterous, laugh-out-loud feats with a cricket ball.

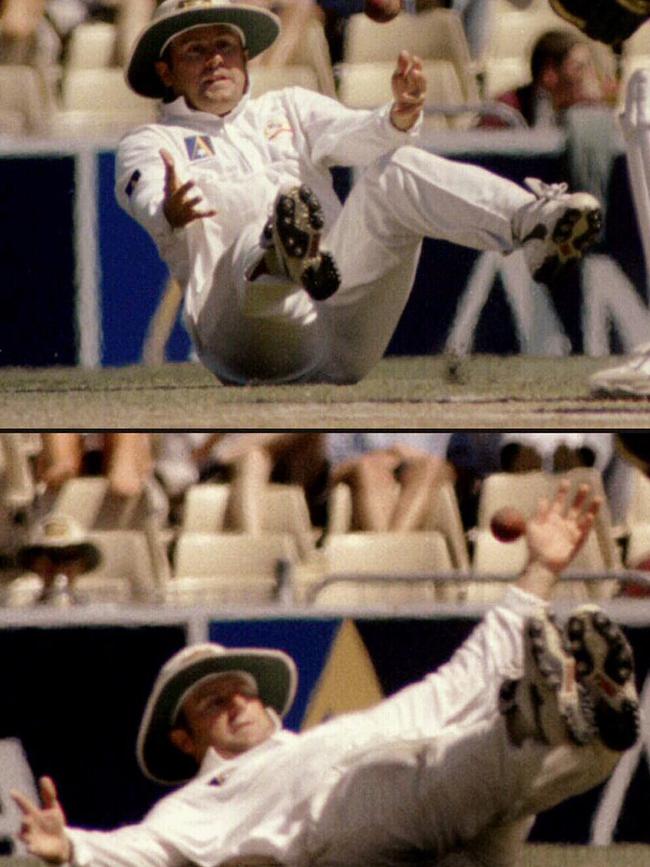

Mark Taylor’s slips catch with his feet

Dropped catches are a natural source of cricketing comedy. On rare occasions, however, we can find mirth in a catch that was successfully taken. Most often any fun in a completed catch arises from a cricketer almost dropping the catch (you can’t get away without at least the threat of a drop being at the comic core), before circumstances conspire for the chance still to be held.

Sometimes the catch is rescued by an alert teammate who cleans up a fellow fielder’s sloppy hands with quick reactions and sharp attention. This, for example, is what happened in 1982, when, with three runs needed to win, Jeff Thomson edged the ball to slip to end his extraordinary tenth-wicket partnership with Allan Border. Chris Tavare dropped Thomson’s chance, only for Geoff Miller to swoop around behind and take the rebound.

In modern times, there is hope for hilarity in the deliberate parrying of a ball from a fielder leaping over the boundary rope to a teammate (or their future self) inside it. Most times, however, any amusement from such a moment is really startled delight at the astonishing display of dexterity. It’s not really comedy.

So can we actually create genuine comedy from a successfully taken catch?

Yes, we can. But it requires Mark Taylor, one of the great slip fielders of all time, to watch Michael Bevan land a perfect wrong’un with his left-arm wrist spin, fall on his back as the edge from Carl Hooper comes his way, have the chance burst through his first snatch at it, rebound off the brim of his hat back towards his legs, kick it in the air with his flailing feet, then have the ball settle back in his hands, while still lying on his back.

There’s comedy in that. There’s top-shelf comedy.

Mike Gatting’s befuddled ball of the century reaction

There’s a moment of delight when we see a particularly clever magic trick. When the only rational reaction is to laugh at how efficiently the magician has fooled us.

We originally experience this delight as infants, when the trick is as simple as our mother hiding her face behind her hand, only to dramatically reveal it via the cheery magic word ‘peekaboo’. Aha! How wickedly entertaining, Mother. Bravo.

But when we think of Mike Gatting being bowled by Shane Warne’s legendary ‘Ball of the Century’, the swerving, biting, turning, stump-rattling first Ashes delivery of his Test career, it can evoke other, more complicated emotions.

What’s so funny about that moment is that everybody watching on television has been given a perfect view of Warne’s magic. (“Ah, yes, I see. The rabbit was in a secret compartment all along. Excellent.”)

It’s only the players on the ground – and, in particular, Gatting – who don’t really understand how the trick worked. (“Where the hell did that bloody bunny come from?”)

After Warne bowls him, Gatting’s facial expression cannot hide his confusion. How did the ball beat his bat? Or his body? And still hit the stumps?

This was unquestionably sorcery of the highest order, and while Gatting cannot, by the nature of the Ashes contest, be truly delighted by it, he cannot help but be impressed.

He steps back into his crease as if somebody might shortly explain to him that this was just a silly prank and he will, in fact, be permitted to face the next ball.

He then frowns at the square leg umpire, curious about how, exactly, the bails have been removed, because surely he can’t have been bowled. That wouldn’t make any sense.

Reluctantly, he walks away from the crease, his face still awash with confusion. As he removes his gloves, he gives a small headshake and a raising of the eyebrows.

It’s bewilderment. It’s admiration. And you’d like to think that, as a professional cricketer who devoted his life to the sport, there might even be a skerrick of delight in there.

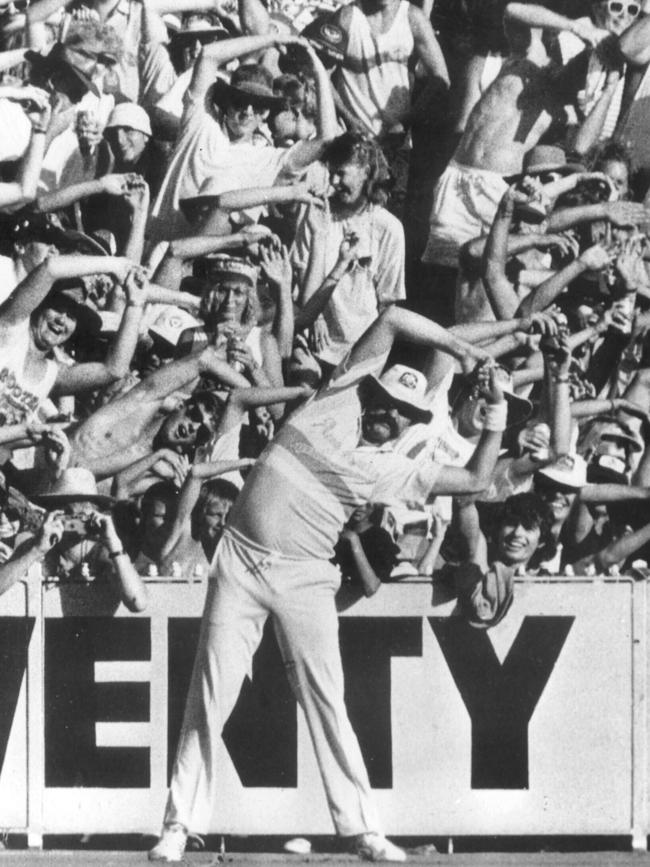

Merv Hughes’ Bay 13 aerobics session

Merv Hughes is a classic Australian archetype. A big man. A big fast-bowling man. A big fast-bowling man with a big fast-bowling moustache, who captured the imagination of Australian fans.

No moment demonstrated Merv’s hold on Australian crowds better than the time he led an impromptu aerobics session at the MCG during the first final of the World Series Cup on January 14, 1989.

Merv was a superstar who only needed one name to define him, à la Madonna or Bono or Popeye.

Australia were defending just 204 from 50 overs that evening against the West Indies. Merv had shared the new ball with Terry Alderman and had done his part, removing both Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes.

However, captain Allan Border needed more from his moustachioed hero and gave him the heads-up that he’d be returning to the bowling crease shortly.

Merv, fielding on the boundary in front of a packed Bay 13, in an era where one-day internationals were prone to packing out not just bays but entire stadia, began his warm-up routine.

And so did the entirety of Bay 13 behind him.

Merv stretched to the left.

Hundreds of fans stood and did the same.

He stretched to the right. The fans followed his lead once again.

Merv bent backwards, swung his arms in circles and pretended to be an aeroplane. The fans emulated him each time.

When Merv was done, he was ready to bowl. And every single person at the ground and watching on television was in his corner. They may not have had ball in hand, but by joining in the warm-up, they felt as if they could have.

The crowd warmed up with Merv that night (and every night from then on), but that was not the night they’d warmed up to Merv. That had happened long before.