What Dan Andrews and late British PM Margaret Thatcher have in common

Labor insiders have revealed what they really think of Dan Andrews, with one saying the Victorian Premier shares much in common with ‘iron lady’ Margaret Thatcher.

VWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from VWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When Daniel Andrews fractured his spine after falling down wet stairs in Sorrento, his former chief of staff John McLindon visited him in hospital.

Andrews was hooked up to machines in intensive care and looked haggard. He was clearly in pain, having refused surgery to insert pins and rods in his back.

As Victorians and the premier’s colleagues contemplated a post-Dan government, Andrews was unflinching about his return to the top job.

“I’ve got to get right, people are relying on us, we’ve got s--t to do,” he said.

McLindon, who worked with Andrews when he was in opposition and government, says it showed many people misunderstood Andrews because “the harder it gets, the harder he fights”.

The brawler mentality has defined Andrews during his career, but those who have been close to him are divided about the layers beneath the hardened political persona, and what drives him.

Is he a “dictator”, or determined?

Fearless, or friendless?

Intimidating, or insecure?

After almost eight years in power, the question remains: Who is Daniel Andrews?

MAKING THE MAN

What do Margaret Thatcher and Daniel Andrews have in common? More than you would think, according to one close observer.

Thatcher – who marketed herself as the daughter of a humble shopkeeper – was uncompromising in pursuing political objectives.

Andrews has pitched his own story of a country boy with humble farmer and small business owner parents, and has himself ruthlessly pursued his political objectives.

Friends and foes remember Andrews visiting the family farm in 2014 while his father Bob battled cancer, as the then-opposition leader sought to humanise his candidacy.

Some were taken aback he put his family on stage during a personal health battle, while others said it was the obvious move to broaden his appeal in regional areas.

As mid-tier landholders near Wangaratta, the Andrews family had a relatively comfortable life.

“They weren’t poor,” one Labor veteran says.

But one Andrews ally says the family’s small business challenges shaped his view of the world.

The family was Catholic and Andrews attended Galen Catholic College.

During a visit when he was opposition leader in 2012, a former teacher remembered Andrews as a “meticulous” student with great aptitude for assessing election results, while an MP noted he “wasn’t in the in group”, and has tried “to prove for the rest of his life that he should have been”.

After studying politics at university he worked for Labor powerbroker Alan Griffin, a leader of the Socialist Left “southeast crew” in Melbourne’s southeastern suburbs.

He engaged in factional battles and party recruitment in his early 20s, which former rival Adem Somyurek recently told an anti-corruption hearing was “branch stacking”.

One Labor source familiar with the period said many people were involved in party recruitment in the 1990s and it was “not illegal”.

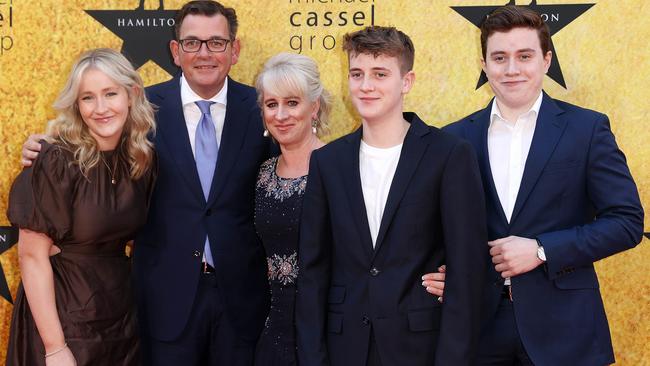

In 1998, the 26-year-old married Catherine Kesik – his self-proclaimed rock and mother of their three children, Noah, Grace and Joseph.

As an assistant secretary of the ALP, Andrews went on to play an important role co-ordinating country and marginal seat campaigns during the 1999 state election, according to the man who became premier that year, Steve Bracks.

“He was someone who was old before his years, in some ways he always had an old head on him,” Bracks says.

“He was in his 20s for goodness sake, but you would have thought he was a seasoned operator in his 40s.”

Entering parliament in 2002 when his son Noah was four months old, Andrews was soon appointed to cabinet, backed by another Socialist Left numbers man, Gavin Jennings.

He was promoted by John Brumby in 2007, when Bracks retired.

Former sports minister Martin Pakula says he realised the scale of Andrews’ influence in 2010 when Lynne Kosky resigned and a public transport ministerial replacement was required.

“I see Daniel – he’s health minister but only been in cabinet three years. As a joke I put my arm around him and say ‘how does it feel to be the new public transport minister?’ Without batting an eyelid he says, ‘I don’t know mate, you tell me’. I said ‘yeah right’, but he replied, ‘I’m telling you, get ready’.

“Only then did I realise he was the bloke Brumby was talking to … about who would get what in the reshuffle. He was 38, but he was already massively influential.”

Senior figures say Jennings and Griffin were critical figures in his rise. They say this makes the recent falling out between Andrews and Jennings, who left parliament in 2020 in a “bitter” state, more remarkable.

“Daniel hasn’t reached out once, since (Jennings) left,” one says.

MAKING OF A LEADER

When Andrews became Labor leader in 2010, he worked key business leaders and studied marginal seats in the belief the party could win government after one term in opposition.

Senior right wing operatives believed he would fail, so sat back and watched him sail towards what they thought would be an “honourable loss”.

“Daniel knew he had one shot,” one Andrews loyalist says.

He worked at a frenetic pace which sometimes led to angst, with one insider noting “he doesn’t sleep much” and another noting similarities with Kevin Rudd.

His ruthless political style was shining through as he made inroads against a fragile Liberal government.

Some inside the party warned against trashing parliamentary standards but Andrews argued – and won out – that the optics of chaos would benefit him in the long run.

At one stage he was suspended from parliament after a walkout of MPs.

Former Liberal premier Jeff Kennett says part of Andrews’ long-term legacy will be the “failure to uphold the finest principles of the Westminster system”.

Labor MPs brush off criticism but say it shows who Andrews is, and why he’s different to other leaders like Bracks and Brumby.

There were crises during his time in opposition that could have killed off a weaker leader.

These included the leaking of tapes from a journalist’s recording device left at a Labor event.

In July 2014, Andrews told the media that ALP operatives had listened to recordings on the device, which included a conversation with former Liberal premier Ted Baillieu.

Multiple sources say Andrews listened to the tapes – despite him claiming later he found out about the recordings “when it was made public” – and that the Premier’s adviser Lissie Ratcliff, now his chief of staff, was involved in sharing the recordings.

Andrews was resolute that “nobody in my office had any involvement in the distribution of this material”.

One Labor figure says whatever the truth, it was symptomatic of how Andrews and parts of his office operated: “His default is deny, and keep going. You can’t be honest.”

The “deny, and keep going” mantra reappeared in government when whistleblowers revealed Labor had misused MP parliamentary budgets to pay for 2014 state election campaign staff.

Referred to as the “red shirts rort” due to the campaign staff wearing red Labor shirts, it saw the ALP cough up almost $400,000 in repayments.

The Premier’s initial response was to deny wrongdoing while keeping the wheels of government – including his infrastructure building program – turning at a frenetic pace.

The public, he gauged, would move on.

The proof of that, his supporters say, was the landslide 2018 election win.

Another Labor source says although Andrews is an impressive leader, recent state Labor victories in Victoria were like Russian army triumphs in 1945: “The Wehrmacht were s--t, it is hard to lose.”

WHAT DRIVES DAN?

“He’s obsessed with winning,” one Labor figure says. Deputy Premier Jacinta Allan describes it as “determination and drive”.

And retiring MP and former police minister Lisa Neville says he has been better than Bracks and Brumby in terms of “clarity on issues, his drive and expectations”.

McLindon says his 2018 election success was built off doing what he promised, using the dumping of the East West Link to highlight that point.

In 2015, prominent members of the business community believed the Premier would backflip and build the toll road under central Melbourne.

McLindon said this would have delivered “a quick sugar hit in the media” but then left him forever branded a liar.

He describes Andrews in golf terms, saying most people stand on the tee and look at where they want to hit the ball, while the Premier imagines himself on the green and looks back at the shots he needs to get there.

Some within Labor say he’s a lefty, others call him a pragmatist. “His instincts take him to the middle and things he knows,” one insider says.

Those close to the Premier say Andrews always wanted to climb the social ladder, and prove himself to those at the top end. He enjoys a drink with members of Melbourne’s rich list.

One Labor figure who has worked closely with the Premier says they did not often see evidence of close friendships.

“I don’t know if he has any friends, and I’m not trying to be mean,” an MP says. Another says: “He has friends he goes drinking with”.

When Andrews fractured his spine in 2021, the reputation for a tipple with the top end of town was enough to spark wild rumours he had been boozing with trucking magnate Lindsay Fox, and friends.

“When you then started hearing rumours that he’d acted inappropriately with someone’s wife you knew it was all bulls--t,” one MP says. “Dan might be a lot of things, but he’s not that.”

It’s no secret Andrews has a strong relationship with Fox and some of his children, and has backed their projects.

The Fox name will also be attached to the new NGV Contemporary after a $100m donation.

Former state ministers see the Premier forging a pathway towards a post-politics career in the corporate world, with one pointing to the relationship with Andrew Fox, who is also close to Greg Norman.

Andrews’ obsession with golf is personal, and Melbourne will host the Presidents’ Cup tournament in 2028 and 2040 because of it. Wife Catherine insists to staff he keep Sunday afternoons free for golf to balance out a relentless work schedule.

Insiders say a personal connection to policy or projects is often crucial to getting Andrews’ support. They point to a meeting with a young boy – Cooper Wallace – and his family in 2014 that saw the then-opposition leader embrace medical marijuana at a time when he was being branded a “lefty”.

Others point to the experience of his father battling severe illness as a reason he could be convinced to pursue voluntary euthanasia and break a personal pledge to his loyal deputy James Merlino.

Before that radical reform was adopted, key lieutenants such as Jennings and Jill Hennessy tested the waters.

At one point Andrews almost threw in the towel, but was convinced to continue due to polling showing popular support.

One of his factional opponents describes him as “a pragmatist”, but a Bracks-era MP says that is misleading because he has been “extremely ideological” in allowing sweeping social changes to occur.

A close colleague of Andrews’ adds nuance, saying the Premier adopts social causes – such as taking part in the Pride march – if he believes people are behind the cause and it can deliver “an additional constituency”.

They say the personal connection to the LGBTI community via Ratcliff is also instrumental, due to being advocates he knows and respects.

GETTING PERSONAL

Those who know Andrews will admit he can be harsh and crass. His fondness for dirt on parliamentarians is renowned, while he has nicknames for many MPs and journalists – usually revolving around weight, appearance, or rumoured relationships.

One Coalition MP was referred to as “Grimace” – the rotund purple creature who featured in McDonald’s advertisements.

A Labor backbencher was referred to as “the drug addict” due to their rumpled appearance – something the Premier denied via a spokeswoman this week when approached for this article. The Premier and his office declined to comment further about this or other matters put to them.

Occasionally, sledges have become public.

In 2016, Andrews strenuously denied Labor MP claims that former Carrum MP Donna Bauer would be “s--tting in a bag” due to a cancer diagnosis.

But he admitted to jeering at former Liberal MP Andrew Katos over his weight the same year, and apologised.

“His humour is always putting someone down. He’s not a very nice guy,” one Labor MP says.

In a section of his forthcoming book, former minister Somyurek describes an early Covid briefing about cancelled surgeri

es, during which a minister undergoing IVF argued the sector should get exemptions.

“Andrews rolled his eyes and dismissed it based on the line of argument that ‘furniture removalists would want exemptions next’ if her medical procedure was permitted,” he writes in Adem Somyurek: The Faceless Man.

Andrews’ response “raised eyebrows for the lack of sensitivity in drawing an equivalence between a medical procedure and removing furniture” and was “deemed much more insensitive because the topic related to women’s health”.

“This was not the only time in a cabinet meeting that Andrews’ lack of thought before opening his mouth caused alarm.”

The minister, Gabrielle Williams, has disputed Somyurek’s version of events, including the Premier’s eye roll, but did argue for IVF exemptions based on urgent need rather than her own situation. Some close allies of Andrews dispute the broader connotations.

But Andrews’ enemies and the state opposition have frequently seized on the narrative to argue the Premier has a problem with strong women.

This took hold during a dispute over a Metropolitan Fire Brigade workplace agreement that thrust then-emergency services minister Jane Garrett into battle with the United Firefighters Union.

While in opposition, Andrews had made commitments to UFU boss Peter Marshall in a signed letter provided to unions by Labor leaders before elections.

That deal was later included in a probe of the fire services by the state’s anti-corruption commission, to which Garrett gave evidence.

Sources say Andrews must have responded to that investigation, but his office declined to comment or confirm his involvement.

It is one of three IBAC probes that have embroiled Andrews, with the other two involving political donations and branch stacking.

Labor insiders say there was nothing remarkable about providing a signed letter of promises to the UFU, which were also provided to paramedics, nurse, police and other key stakeholders or unions. But multiple sources say a unique aspect was that Wade Noonan, who was the shadow minister in 2014, rejected the portfolio when offered it by Andrews after Labor’s election victory.

Noonan denies this version of the story, saying he believed three portfolios he held in opposition – emergency services, corrections, and police – would be too much for a ministerial newcomer and that he asked for the Premier to give him two.

“I was certainly aware of the opposition’s deal done with the UFU, I was aware of that going into the election,” Noonan says.

“There was absolutely no connection between what was in that letter and my willingness to take on the role or not.”

The decision to hand emergency services to Garrett, who died this month at age 49 of cancer, was disastrous.

Garrett decided to stand up to Marshall and “the boys” in the union, and was backed by another enemy of Andrews and strong ALP woman, the late Fiona Richardson.

Andrews met personally with Marshall in 2016, and forced through a workplace deal against his minister’s advice, and in spite of egregious behaviour by Marshall.

After Garrett’s death, journalist Aaron Patrick revealed that she had despaired at the lack of support she received during the bitter dispute, including when Marshall allegedly threatened firefighters would put an axe in her head – something Marshall denies.

Somyurek details some of Garrett’s distress in his book, including after an orchestrated attack during a caucus meeting by senior ministers including Neville and Treasurer Tim Pallas.

Others also remember the incident.

“He (Andrews) could have stopped it, and taken things offline like he usually did,” an MP says. “It was disgraceful.”

Many former and current allies of Andrews remain unapologetic, maintaining Garrett was disloyal.

DAN’S CHRISTMAS PUPPIES

Within Andrews’ office there’s a motto that “stakeholders are not voters”.

The view of people in suburban seats trumps stakeholders agitating for a certain course of action.

One senior Labor figure describes some naive interest groups or MPs as “Dan’s Christmas puppies”, brought in with tails wagging but once their purpose has expired, they are left neglected or returned to the pound.

One former minister who remains a supporter of Andrews says there “has been a concentration of power within the Premier’s office and around him”.

“That power has been absolutely concentrated and the function of cabinet is not what it once was,” they say.

Some senior party figures now say the “cult of Dan” could be dangerous for the ALP long-term. They point to the fact that political advisers in the Premier’s Private Office were left in charge of the party platform that are an election blueprint.

A Socialist Left factional meeting recently blew up over the PPO go-slow, with one operative lashing the Premier.

“He’s turned Labor into a wine tasting, fundraising club,” the operative said during the meeting.

Others disagree about the Premier’s influence on Labor politics.

Luke Hilakari, who worked for Andrews when he was health minister and now is Trades Hall Secretary, says the Premier’s introduction of industrial manslaughter and wage theft laws are watershed moments.

Changes to nurse-to-patient ratios are also significant, and secured through Andrews’ strongest relationship with a union leader, Australian Nurse and Midwifery Federation boss Lisa Fitzpatrick.

Hilakari says Andrews as a leader has some similarities to former Liberal premier and political nemesis Kennett.

“He’s a premier that gets things done,” Hilakari says, borrowing Andrews’ own phrase. “They might not be universally liked.”

He also points to the Premier’s reception to a joint approach by the Victorian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Trades Hall for a jobkeeper-style payment during the pandemic.

Andrews has shown himself a master deal-maker during his career.

“He sees five steps ahead of most people,” one Labor MP says.

A party figure says “everything is a deal for Daniel”.

Some point to the case of Allan being effectively announced as deputy premier before factional processes took place.

Andrews had done a deal with the AWU-aligned grouping outside of a factional stability agreement, which saw Natalie Hutchins and Colin Brooks promoted, to smooth Allan’s path.

This angered others in the stability agreement, including the Premier’s own faction.

One senior Socialist Left figure says the Premier has almost “unfettered power” due to the recent exit of factional figures and party elders and the fact the national executive has been in charge of the Victorian Labor Party since 2020. “He’s a tyrant, and he’s getting worse,” the figure says. “But his power evaporates as soon as he wins (the November election). People say, ‘you are retiring, and we don’t care about what you say because you are retiring’.”

Those who remain close to Andrews dispute the “Dictator Dan” tag that developed during the pandemic and say he and the PPO – do consult.

The boss of the Australian Hotels Association, Paddy O’Sullivan, says the relationship between the AHA and government is strong due to consultation.

He acknowledges the relationship “was tested during Covid restrictions when pubs were severely affected by the ever-changing rules” but an ongoing dialogue saw subsidies of up to $20,000-a-week introduced.

“The Premier has shown a commitment to work with our industry to help pubs recover,” O’Sullivan says.

Andrews has always been close to the pubs group, which he knows can impact election campaigns, and even delivered a eulogy at the funeral of former national president Peter Burnett in 2019.

One Labor elder says the belief that Andrews “gets his own way” on everything is limited because “he’s very conscious of the powerful people in the party and the ones who can damage him”.

“I think he’s a person who is fearful of things, even though he comes across as this fearless leader,” they say. “He’s got so many of these contradictions. The one thing that saves him is he’s a good performer publicly.”

NORTH FACE DAN

In early 2020, then-assistant treasurer Robin Scott cut short a visit to his wife’s home town in China and flew back to Melbourne.

Multiple ministers say Scott, dubbed a worrier by the Premier, relayed an urgent message to cabinet about lockdowns and the fight against a probable pandemic.

Several current and former ministers remember a special cabinet meeting convened in February 2020, when chief health officer Professor Brett Sutton projected the number of deaths and hospitalisations expected if the coronavirus continued to infect and kill people at the rate being seen in other parts of the world.

“Everyone just shat themselves,” one says. “Daniel was kind of in denial at that stage. He took it offline like he always does in those situations.”

The pandemic changed everything, but Andrews’ style remained largely the same – if not more so once he chose to create a crisis council of cabinet with key ministers.

Colleagues say he could handle the daily press conferences due to his incredible memory.

Hilakari tells a story that highlights the Premier’s recall, when a nurse in an elevator said to Andrews “you wouldn’t remember me”.

The Premier promptly rattled off her job in the maternity ward at a suburban hospital, where twins had been delivered during a previous visit.

A former Bracks and Brumby era minister says “he’s capable of holding a lot of facts in his head, he’s very intelligent, but he’s not an intellectual”.

Colleagues say Andrews loved to strut on the national stage, which he did with ease until the state’s hotel quarantine scheme blew up.

Once Covid-19 cases started to seep out of hotels, via security guards who had no training in infectious disease control, Andrews had to change tack.

Somyurek, who was twice appointed to Andrews’s cabinet before being accused of branch stacking and quitting, has publicly criticised altered cabinet processes that contributed to the situation.

One member of the crisis cabinet, Neville, defends the process and says the Premier always ensured buy-in from across the table from those he trusted to do the job.

“He sets high expectations and if you are not meeting it, you will get a sense of it,” she says.

Others weren’t critical of processes but concede the decision to “keep hotels functioning” for a quarantine scheme was the wrong starting point.

An inquiry into the scheme, which is blamed for the virus re-emerging in Melbourne and killing 800 people, saw no one take responsibility for hiring security staff as part of the operation.

Health minister Jenny Mikakos walked the plank, along with secretary of her department, Kim Peake, and the secretary of the premier’s department, Chris Eccles, after the Premier “threw them under the bus”.

Several MPs describe the Premier’s testimony during that inquiry as curious given his tendency to remember events in incredible detail. Others say a premier would always be protected in such situations, and instead criticise Mikakos.

Liberals say Andrews’ “narcissism” shone through during the pandemic, and some theorise the “I Stand With Dan” hashtag that swept social media was created by Andrews.

Opposition Leader Matthew Guy continues to prosecute the argument that Andrews has made the pandemic about himself, rather than the safety of the state: “This Premier lies, berates and misleads Victorians. We all deserve so much better than that.”

NEAR (POLITICAL) DEATH EXPERIENCE

Andrews recently opened a golf course and was encouraged to tee off for the event.

He declined, explaining the need for 30 minutes of controlled warm-up exercises before swinging a club, after his fall in March 2021.

Insiders say he still experiences pain today, while some Labor MPs say it could help explain bouts of “angry Dan”.

Despite the severity of the injuries he suffered after the fall down a set of stairs, few doubted he would return to centre stage.

Some MPs believe Andrews is back to secure his legacy, which would be damaged by the pandemic if he left without addressing the pain and suffering caused to so many by lengthy lockdowns.

Andrews told the Guardian: “I got fit and well to come back, not to piss off. I’ve got a lot to do.”

But a senior Labor source says “I don’t count on him staying much past the statue” – referring to the custom of premiers getting an effigy erected outside 1 Treasury Place after serving 3000 days.

Andrews will pass that mark early next term if he wins at the next poll.

One muses that his exit it could coincide with the opening of the Metro Tunnel, one of his signature infrastructure projects that have underpinned his success.

A close observer of Andrews says the exit from the political stage could have already occurred if it wasn’t for the pandemic when “everything turned to s--t”.

“This entire election is about re-establishing his worth with the private sector,” they say.

“Everything he does is about the ‘next step’ – nothing wrong with that of course.”

The pandemic and Andrews’ injury may have marked significant moments in his leadership, but some ministers say they didn’t alter his mindset.

Deputy Premier Jacinta Allan says while there was a distinction between the “2020 pandemic and the 2021 pandemic” the Premier’s resolve didn’t change when he returned.

“It was very much ‘just get on with it’ because that’s been the way of our government all the way through Daniel’s leadership.”

When asked what the Premier’s legacy will be in decades to come, views differ once again.

Several Labor figures say he won’t catch up with many colleagues in future decades to remember old times, because of his brutal ruling style. The term “ruthless” was used repeatedly, with different intent.

Kennett says the infrastructure created under Andrews will be a legacy, but that he will be remembered “harshly” for the debt he has built for future generations.

The propensity to spend big in government is an Andrews’ hallmark, and is brought up by detractors and supporters alike.

It will continue to be a feature, they say, as he tries to spend his way out of the current health crisis.

Asked about legacy, some colleagues defer to the cliche that he “got things done”.

And that may be enough for Andrews.

One of his closest supporters says that the Premier won’t be losing any sleep.

“I think he knows he’s very misunderstood by people, but he just doesn’t give a f--k.” ■