Three days homeless on streets of Melbourne

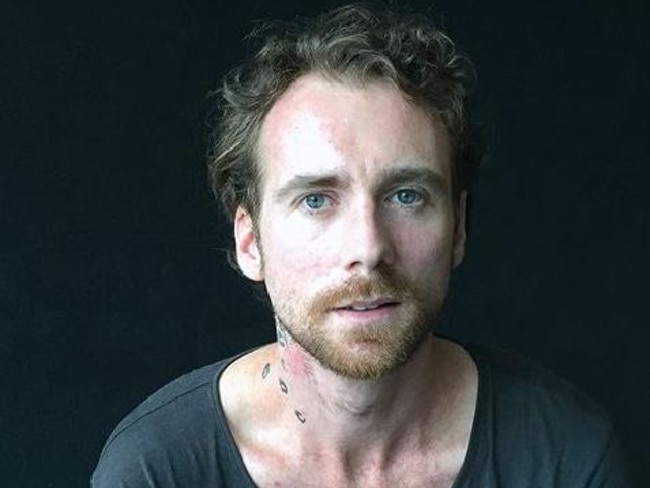

LUKE Williams spent three days living and sleeping on Melbourne’s streets without a single cent. This is what he found out.

Real Life

Don't miss out on the headlines from Real Life. Followed categories will be added to My News.

JOURNALIST, author and former drug addict Luke Williams came back to Melbourne after 18 months in Asia to his city’s streets filled with mattresses and tents. Social service groups describe it as “an epidemic” and “a crisis” and the Salvation Army says this is “the worst homelessness has ever been”. Williams wanted to find out why rough sleeper numbers were at an unprecedented high in the CBD, so he spent three days living and sleeping on Melbourne’s streets without a single cent. This what he found out.

“IT’S ten past nine, time to do some crime, take what’s not mine, make a dime, then some lines and that’s just fine, as long as you don’t do time,” she said, tapping her fingers to the steady, repetitive, bass-heavy beats coming from her smartphone.

Sixteen, with white creamy skin and a blackened front tooth, fresh out of juvenile detention.

A good little rhyme that told the time: ten past nine. It meant 8.45pm was when I started my project sleeping rough in Melbourne city for three days without a single — well — dime.

This 16-year-old girl was one of six homeless people on the cold concrete outside the Swanston St 7-Eleven. I asked if I could sit down with them. We were gathered around a mattress like it was a campfire.

I felt an urgent tap, tap, tap on my arm. “Have this,” a woman, about 32 with Elizabethan skin and a second-hand doll’s haircut, said holding a Twix bar. “You look hungry,” she added.

I eat the Twix and she introduced herself as Melissa. I liked her. The guys in the group didn’t. “Can I please have a bong?” she asked, to which he replied, “only if you f*** off”.

“Heyyyyy,” she said. “Listen, let’s not fight. We could all get a house together y’know — all of us share a house? It’s sh** being homeless. Why don’t we get a house together?”

What a bloody good question. In June this year, a biennial street count showed there had been a 74 per cent increase in the number of homeless people sheltering on the streets of Melbourne’s CBD. Social service groups said 2016 saw the worst homelessness ever in Melbourne. I’ve come back from 18 months to Asia to find laneways in my affluent, liveable, left-liberal city have become filled with tents, tarps and beds, clothes are drying on Flinders St station handrails.

In 2016, for the first time in our history, there are about 30 homeless camps at any one time across Melbourne’s otherwise elegant streetscapes. On the first night I went for a walk, I met an autistic teenager, a legless man, a 60-year-old woman with a German accent and a cute cat, and a transgender girl who changed wigs three times while telling me how her parents kicked her out of home.

I met Lauren a bit after the transgender girl took off her wig altogether and started jogging around the block to keep warm. Lauren was in Horsham for four years, and said she had been living on Melbourne’s streets since her house burnt down a month ago.

“Eight weeks to go, mate,” the 29-year-old said.

Lauren was pregnant: obvious because of her small frame.

“Why aren’t you on a priority list?” I asked.

“I am, we are all a priority list,” she explained through her rough, rural, fatigued accent.

“We are all ‘high-need’ clients,” and social services won’t put her in emergency accommodation unless she gives up Martie, her dog.

I asked Lauren if I could see where she sleeps because, to be honest with you, I was not sure if she was telling the truth. I wondered if Lauren wasn’t just using her pregnancy to get money begging?

“Me and me man sleep in a laneway behind the town hall,” she said.

“Can I come and see you guys there tomorrow night at about midnight?” I asked.

“Sure,” she replied, squinting at me in a way that made me wonder if she knew I wondered if she was lying.

Come 11pm and I was trying to work out my options of where I could sleep — the laneway or the main street.

Why not just walk into a homeless shelter? Australia doesn’t have big communal shelters you can just walk into if you have nowhere else to go. If you go into a social services place, you still have only a 50-50 chance of being given crisis accommodation on any given night.

I curled up in a shop entrance on Bourke St with my backpack as a pillow and went to sleep on an empty stomach. I find if you do that you are often less hungry in the morning. I woke up at 4am that night, hungrier than I’d hoped. It was mild when I went to sleep, but then it was frigging cold. The breeze felt like it was coming from an ice-clad ocean. It was way too loud as well. The city day was starting and I couldn’t go back to sleep.

Clearly I wasn’t looking too happy lying down on my backpack. A garbage collector caught my eye as he hurled rubbish. He stopped, went into a 7-Eleven and came back with a cup of coffee.

“You look like you need this friend,” he said.

The Salvation Army opened for breakfast. It was a decent feed. I could have kissed the volunteer. I hadn’t eaten since that Twix at ten past nine.

At noon, I got lunch again at the Salvation Army. Then came a long, light-headed afternoon. If you’ve got no money in Melbourne there’s nowhere to eat again until 6pm. This leaves three options — steal, borrow or beg.

In her velvet brown jacket and matching pants, Karen looked too smartly dressed to be homeless. She was sitting outside Woolworths, a sign written on torn cardboard in front her: “I am sick, in and out of hospital. I need food, any help is appreciated.”

I sat down next to her and asked what was going on. A year and a half ago her father died. Six months later, her partner (and co-mother of their adult son) was killed in a car accident.

“Then I got sick,” she said, “and I’m still battling with my bloody sister over dad’s will.”

The 49-year-old told me how people she knew were either homeless or living in boarding houses, where having guests stay is often not allowed.

Karen also has cancer. She taps her on her left breast as she tells me how she didn’t want to have the radiotherapy — which “feels like there are pins in your bloodstream” — but her son convinced her to do it. She doesn’t always go to her weekly treatment and, when she does, she leaves the hospital and returns to her mattress on Bourke St a block down from Parliament House.

Karen gave me half a sandwich. She said I was the same age as her son. She looked at the thongs on my feet.

“I can get some socks if you want and a social worker too. But you need to stop this rot about you being a journalist and just tell them the truth,” she said.

After dinner at the Salvos, I discovered there was nowhere to eat from 7pm until morning and I was starting to feel a faint, frustrated and day-dreamy. Then I remembered I had a fact to check. I found Churchbell Lane behind the Town Hall. I had never heard of it, and yet there it was, tiny and narrow and twists and turns. And there she was: Lauren from Horsham sitting on a mattress, pregnant belly protruding. Martie the bull-mastiff barks his head off at me.

“Oh, hey mate,” she said. “I f***in’ told ya I sleep here, didn’t I?”

Yes, yes she did. It’s hard to say exactly why I didn’t believe her. But I began to wonder if people like Lauren and Karen were a more extreme example of those left out of political conversations and left behind by the globalised economy — an abject, Aussie version of the masses who voted for Trump, Le Pen and Brexit.

Night two: I found the Victorian State Government has just funded the Salvation Army to open its cafe at night. The place was packed and all sorts were sleeping over the floor, the steps, and the tables. It opens at 11pm and closes at 6am when the dozens leave and set up tarps in surrounding laneways. I spent the day tired and slightly maniac: a bit savage-animal crazy picking up half-smoked cigarettes out of bins and gutters.

On my final night I slept in the laneway; the Salvation Army centre was too loud too sleep. I was exhausted.

A week later, and I returned to find Lauren and Karen. Eventually, I spotted Lauren sitting in the Salvos cafe with an airline ticket.

“They rang my parents in Rockhampton.” she said. “They were so excited to hear from me, and they have cleared out the granny flat out the back.” The Salvation Army paid for the ticket and she left the next day.

With a lack of accommodation, social workers often rely on this kind of problem-solving — such as family reunification — to get people off the streets. Australia’s annual new housing construction outpaced our population growth from 1946 to 2001. From 2001 to now, the opposite happened. Rents in Melbourne are 46 per cent higher than 10 years ago and 32,564 households are on Victoria’s public housing waiting list.

Nearly everyone in the housing and social services sector agrees with the 2015 Federal Senate Inquiry into Housing Affordability conclusion (rejected by a dissenting government senator report) — we need 7000 new homes built right now specifically for those sleeping rough. But a major question remains: Who is going to pay for it?

I find Karen on her mattress outside a Bourke St 7-Eleven, along with her life’s possessions stuffed into three plastic bags around her. She had radiotherapy again yesterday; she had the blanket pulled over her head. She got up to say hello.

“I’ve got a rotten headache” she said, pulling out some Nurofen. “I need to go back to sleep love.”

She laid down and then back up again quickly.

“I forgot, I’ve got something for you,” she said.

She rummaged through her bag and pulled out a brand-new pair of socks.

“Put them on right now,” she said. “It’s going to be cold later.”

Luke Williams is a journalist and author of Ice Age: A Journey into Crystal Meth Addiction.

Originally published as Three days homeless on streets of Melbourne