Why young people are lining up to become priests and nuns

FAR from being put off by church scandals, an increasing number of young recruits are lining up to take vows of poverty, chastity and obedience.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AMY McCabe was just 12 when she wrote to the sisterhood asking if she could join. Five years later she tried again. While the sisters at the Missionaries of God’s Love welcomed her interest, they encouraged her to get a job and travel before deciding if it really was the life for her.

McCabe worked as a nanny, studied art and threw on a backpack – but her desire never wavered: “It started as a quiet whisper in my heart and the more I came to listen to the voice of God, the whisper grew louder.”

Now 19, McCabe’s life as a novice couldn’t be more different from most teens. She doesn’t have a smartphone and there is no TV or microwave in the convent where she lives in Canberra. Indeed, so “radical” are the poverty orders adopted by the Missionaries of God’s Love that the sisters don’t carry money and instead rely on donated food, clothes and cars to carry out their work. For McCabe, who prays for four hours a day and eats plainly during the week, a treat is a bowl of homemade custard on Saturday night.

But far from seeing her life as one of sacrifice, she embraces values that would be anathema to more typical teens, for whom sisterhood means the Kardashians. “It’s a beautiful thing to rely on God’s generosity and I enjoy a life that’s uncomplicated,” she says. “Social media, parties, money – the things I’m giving up are the things people [wrongly] seek to be fulfilled by.”

In an era of unprecedented opportunity for young women, it’s surprising that anyone would sign up to the Catholic Church’s strictures of poverty, chastity and obedience. But she’s enthusiastic, if considered, as she speaks of a way of life that’s enjoying signs of revival.

McCabe, like all those interviewed for this story, exudes a quiet confidence when explaining the appeal of God at a time when the church has been deeply shaken and the secular world shines more brightly and alluringly than ever. Priest or sister, teen, 20- or 30-something, they’re testament to lives of contemplation and care – even if their beliefs aren’t for everyone.

McCabe says she’s comfortable with her vows because God, not possessions, is what she treasures. And in a world increasingly built on self-betterment and personal branding, her unique selling point is one that’s fallen out of our lexicon: service. “Having a gift of availability for people is beautiful,” she says. “Although working with the poor and marginalised can be confronting.”

Modestly dressed in the order’s “uniform” of a long brown skirt, white shirt and sandals, McCabe concedes it’s the “chastity” vow that most intrigues others. “For me, being a sister is being a bride to God. Every girl has a desire to be fully known and loved by someone. God offers that intimacy, which is why I can give up a romantic relationship.”

And motherhood? “I can be a mother to children in the world who other people don’t necessarily have time for.”

One of six children, she and her siblings grew up near Perth and were homeschooled by their mum. Her parents were supportive of her decision but others were more quizzical. “Some said, ‘What a waste of time, what are you doing that for?’” she laughs.

An easy joy infuses all she does, whether playing sport or seeing the (very) occasional movie. She recently saw Finding Dory after being treated to a ticket. Her verdict? “It was alright.”

Likewise, she does suffer lapses of godliness as per Maria in The Sound of Music: “Sometimes prayer is easy, breezy and I’m thinking, ‘I love being with you, God.’ Other times it drags.”

That sense of humanity is evident in all three of these young people now entering the church in the wake of the great damage caused by the global sexual-abuse scandal.

The clergy abuse hurt me deeply. While we are all frail and sinful, I hope I can contribute to the healing and make amends for those priests

Like seedlings sprouting in a landscape razed by disaster, there’s a quiet humility taking root in place of the arrogance of old. In fact, far from collapsing in the face of the scandal, the priesthood is showing signs of revitalisation. In Melbourne, Wagga Wagga and Brisbane, new rooms are being built in the seminaries to accommodate increased numbers.

At Corpus Christi College in Melbourne, where Cardinal George Pell began his priestly studies and was later rector, numbers are steadily growing. In 1999 they had 28 students; this year they’re in the 50s. It’s a surprise to the current rector, Father Brendan Lane, who thought the priesthood “was finished” after the revelations of child sex abuse. But, he says, the Royal Commission has done them a service. “The focus on abuse has brought to the fore what the church is doing about it. We have rid ourselves of a criminal element.”

He credits the popularity of Popes John Paul II and Francis, the flow-on effect of Sydney’s World Youth Day and, of course, the Holy Spirit for the growth in interest. But the internet, modernisation and enthusiasm for Catholicism in Asia clearly also play their part in spreading the word.

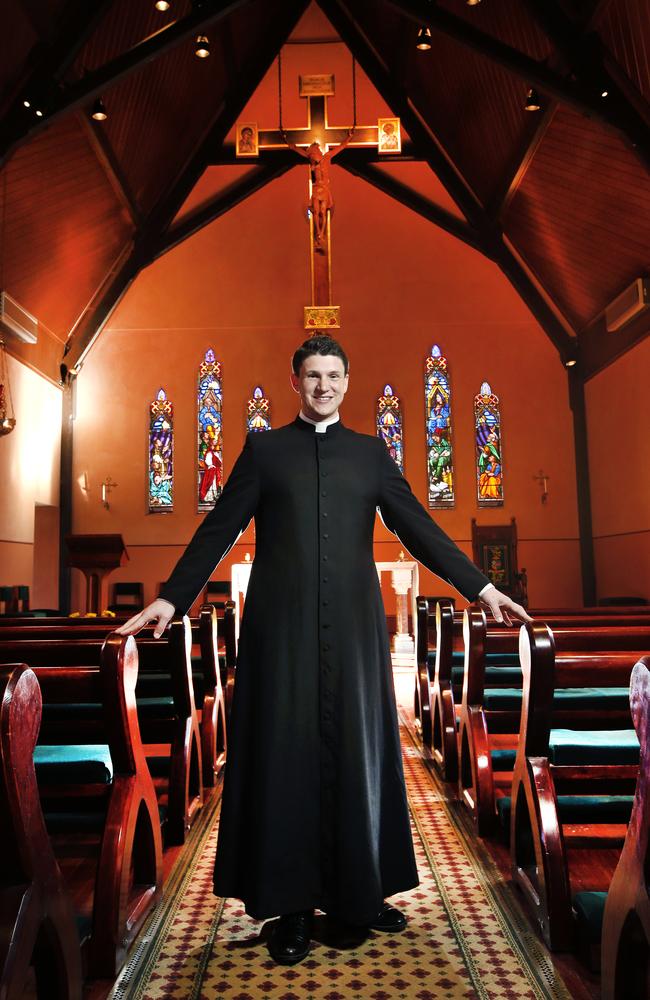

Marcus Goulding, who is in his seventh year at the seminary and due to be ordained a deacon on September 10, believes the church needs good priests more than ever. Now aged 25, he got the marks to study law, but the calling from God was louder. As he prepares for a life of the collar rather than the wig, he feels a responsibility for restoring the integrity of the church.

“The clergy abuse hurt me deeply. While we are all frail and sinful, I hope I can contribute to the healing and make amends for those priests,” he says.

He credits a far more rigorous formation program for ensuring that only those with genuine intentions and sound psychological health are accepted as men of the cloth. “In the past, people became priests who should never have been priests.”

We come from a culture that’s highly sexualised, but not having sex doesn’t make us less human

An altar boy in his local parish, Goulding experienced a calling to enter the priesthood during high school. But when he told his father of his plans, the response was far from positive. “I was a strong academic and had always said I’d do law or journalism, so I couldn’t really blame him,” he admits.

Goulding also had to consider to what extent his parents’ divorce when he was 10 steered him away from the idea of conventional marriage and fatherhood. “I’d love to be married,” he says. “I would bring a lot to being a husband and a father. But as Pope Benedict XVI said, every priest should be someone who is able to be a father, not just in a biological sense but in a human sense. Priests are often called ‘Father’ and that means a lot to me.”

With his two brothers studying medicine and aerospace engineering, he couldn’t have chosen a more surprising career path. While his siblings embrace the pleasures of young manhood, Goulding’s days are full of prayer, study and music. He deleted his Facebook page – “I wasn’t using it constructively” – and embraces celibacy. “We come from a culture that’s highly sexualised, but not having sex doesn’t make us less human.” He’s been attracted to women but chooses instead to recommit daily to his relationship with God. “Love,” he says, “is more important than sex.”

He is also looking forward to wearing the Roman collar because it’s both an external manifestation of his internal reality and an invitation to those in need. “I want to be there for people – to care, to guide, to love.”

Leading Australian theologian Professor Tracey Rowland, who in 2014 was appointed by Pope Francis to the International Theological Commission, says it’s this authenticity of purpose and devotion to God that characterises the new generation. “People are now less likely to use the priesthood as a cover for psychological disorders that make them unmarriageable,” she says with trademark candour.

Being a priest, she adds, is no longer “an automatic pass to social respectability” and those in charge of young priests or novices need to be the best the church can find. “If a person offers to give their life in service, it’s like joining a regiment, with all the risks that entails. They want to feel they’ve joined the religious equivalent of the SAS, not the equivalent of Dad’s Army.”

Indeed, with many responding to the spiritual call after a life in the secular world, the calibre of mentors is critical. In Brisbane, one young man has entered the seminary after a career in the army which included a stint in Afghanistan, while Sydney’s Sisters Of St Joseph Of The Sacred Heart convent is home to a novice who’s worked as both a graphic artist and snowboarding instructor.

The relationship I have with God is greater than romantic love, it is a calling, so I don’t feel I’m losing anything

The notion of a nun on a snowboard might inspire mirth, but 36-year-old Jane Maisey is quick to clarify she has no immediate intention of fusing her talents. Working in Colorado one season, she received regular marriage proposals from an 80-year-old Austrian instructor, but his loss is clearly the church’s gain.

While working as a graphic designer in Christchurch, Maisey’s calling came in the wake of the devastating 2011 earthquake. When people are killed, injured and lives are changed forever, you reassess, she says. “You have a choice of how you come out of something like that and I chose to grow.”

Having grown up as Catholic and after investigating other religions, she found it was ultimately the teachings of Jesus that resonated most deeply. “I was sitting in a cathedral and the idea came to me that I should become a sister. I thought, ‘Oh no, that’s crazy’, but the feeling did not go away. With time, through prayer and discernment, the call became stronger.”

Four years later, as she poses for our photographer in the Mary MacKillop Memorial Chapel – she refuses to clasp her hands in front of her for fear of looking “too pious” – Maisey is everything the church needs in this period of transition. In her Adidas trainers – “they go with everything” – and with her quiet wit, she deftly straddles both the holy and earthly, although she would modestly bat away such a suggestion.

“I’ve lived in the world, so I can identify with people’s pain,” she says. “I’m grateful for every painful experience, all experiences are gifts from beyond and I wouldn’t want to come into this life without it.”

But having had a successful career and freedom for, among other things, intimate relationships, surely the vows of the sisterhood are challenging? “I was never motivated by money and the relationship I have with God is greater than romantic love, it is a calling, so I don’t feel I’m losing anything. I’m human, I’m aware of the male form, but big love is what I’m here for.”

Originally published as Why young people are lining up to become priests and nuns