‘This is how I’m going to die. It’s so unfair’: Turia Pitt’s tale of survival

SIX years on from the bushfire that changed her life forever, Turia Pitt reveals how the love and support of her family and her fiance stopped her from becoming a “whinger”.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

TURIA Pitt calls it simply “the fire” – the horrifying day that divided her life into “before” and “after”. Much as she’d like to put it behind her, it’s an intrinsic part of who she is. Telling her story, she says, is like watching a horror movie. It gets less scary every time you see it.

She wasn’t going to take part in the ultramarathon, a 100km run through Western Australia’s Kimberley region, in September 2011. Not because she didn’t think she could manage it – she’s the sort of girl who’s always bitten off huge chunks of life – but because it cost $1500 and she and her boyfriend Michael Hoskin were saving for a holiday.

But the organisers wanted some locals in the race and Pitt, a 24-year-old engineer at a nearby diamond mine, clearly brought both guts and glamour. When they said they’d waive the fee she agreed in an instant.

Pitt had been running for 19 kilometres and had just passed the second checkpoint when she headed down into the Tier Gorge. Removing her earphones to exchange pleasantries with a couple of fellow competitors, she heard a roaring noise in the distance and thought it must be trucks on the highway.

With shoulder-high desert grass on either side of the track and with her earphones back in, Pitt continued downwards, unaware of the grassfire snaking up the valley floor to her right. Runners behind her had spotted the danger and could see that the slim young woman, running with her eyes down and listening to her iPod, was heading straight towards it.

And then she looked up.

“There was a wall of flames approaching me and I could hear the rumbling and feel the heat,” she recalls.

A surgeon later commented that she’d been “literally cooked” down to the bone.

Pitt sprinted back up the track where she met five others desperately trying to decide what to do. The path they’d come down was shrouded in smoke, and while she knew she couldn’t outrun the fire, the only other option was to remain where she was and be engulfed by the blaze.

“I could see a rocky outcrop up the hill and hoped there’d be a crevasse or a depression I could hide in,” she says. “I was crying as I tried to clamber up the slope, knowing it was life or death. I remember thinking, ‘This is how I’m going to die. It’s so unfair. I’m not going to see Michael again.’”

As she felt the flames licking at her feet and the heat melting her skin, Pitt pulled a long-sleeved shirt from her backpack, covered her legs and curled into a ball. But the heat was too much. She couldn’t breathe. She stood up and tried to scramble further up the hill but the fire caught her.

“I remember looking down and seeing my hands and arms ablaze,” she recalls. As pain ripped through her body she could hear screams that sounded like a wild animal. “Then I realised it was me,” she says.

And with that, the fire had passed.

Pitt didn’t know it, but the fire had burned so deep into her skin it had cauterised her nerve endings. She doesn’t remember much about the next few hours as uninjured runners raced round trying to make her comfortable, but recalls an ambulance officer, who she knew, arriving at the scene.

“Hi, Bonny,” Pitt said to her, but there was no recognition. “It’s me. Turia,” she added, and when her friend began to cry Pitt realised she must have been badly burnt. “Mate,” she remembers thinking, “maybe this is worse than you think.”

It was worse than anyone could have imagined. With burns to 65 per cent of her body, including her face, neck, arms, hands, legs and some of her torso, a surgeon later commented that she’d been “literally cooked” down to the bone.

“I cried reading Michael’s chapter because he doesn’t talk that much.”

Five and a half years later, Pitt only becomes emotional when she thinks of how traumatic it must have been for those she loves. “It would have been so horrible for my mum to think that her daughter might not live. Michael, too. He wasn’t imagining it – it happened.”

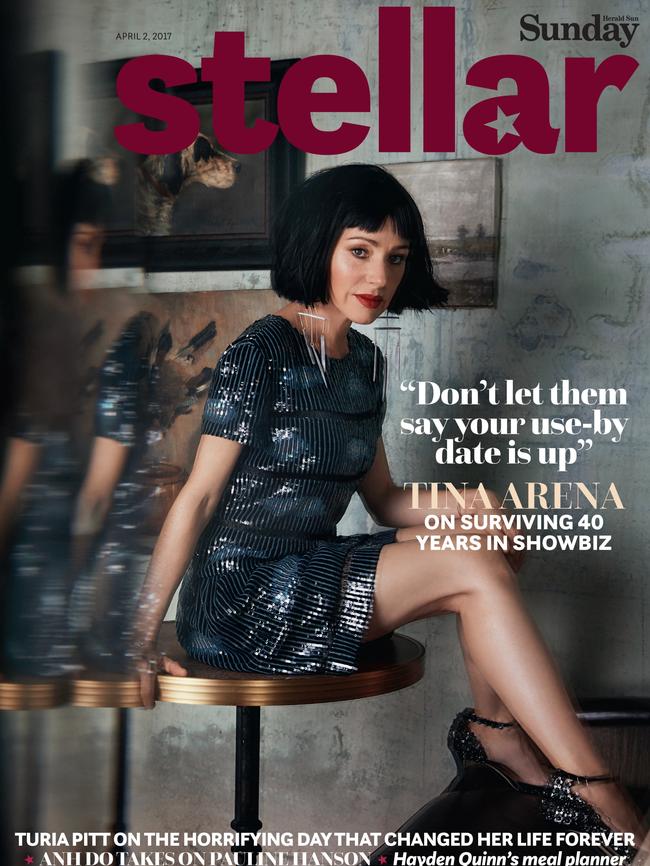

As she bounces on a mini trampoline for Stellar’s photo shoot, it seems as if Pitt is propelled by an extraordinary combination of medical prowess, good fortune and an indomitable spirit. When she speaks, the scars, the melted skin, the horror of that day seem to fade away and what’s left is a woman full of such insight and purpose that you see why she doesn’t want “the fire” to define her.

“Do you know,” she says, “that you’re the average of the five people you spend the most time with? If you surround yourself with whingers, that determines what you’ll be. I’m lucky I’ve got

go-getters around me – Mum, Michael …”

Pitt’s story is as much about love as it is about survival. While her fortitude has captivated the nation, Hoskin’s devotion and loyalty has claimed our hearts. For nearly six years – and two before the fire – he’s been by her side, changing bandages, unscrewing jars and telling her it’s up to her whether she enters an Ironman event or not.

“Oh, everyone loves Michael,” Pitt sighs with faux annoyance when his name is raised. And she adores him, too, chronicling how he had to do everything for her from tying her shoelaces to scratching her itching skin. “I was too reliant on him – I was like a little kid wanting Mum to do everything – so I had to learn to be independent. Now I’m really stoked at being back to boyfriend and girlfriend, not patient and carer.”

Hoskin’s chapter is her favourite in her new memoir, Unmasked. While Pitt tells most of the story, key figures – such as her mum, dad, Michael and others caught in the fire – also reflect on their memories, giving the book both depth and varied perspectives. “I cried reading Michael’s chapter because he doesn’t talk that much. I talk a lot, so people know if I’m having a bad day, but Michael keeps his feelings to himself.”

“I’ll be the disciplinarian and Michael will be the favourite parent.”

One of the most touching elements of the couple’s story is Hoskin’s decision to buy an engagement ring for his girlfriend as she lay fighting for her life in Sydney’s Concord Hospital. He had seen one he liked in a jewellery store linked to the mine where Pitt worked, so he arranged to buy it and secretly gave it to his dad. He didn’t tell anyone else in case she didn’t make it.

Four years later, in the Maldives, Hoskin asked Pitt to marry him, presenting her with the ring he’d kept through all the years of pain, surgeries and rebuilding of confidence.

She’s often asked if she ever worried he would leave her. She wasn’t. As she says: “People tell me I’m so lucky to have Michael – but I’m pretty awesome. I didn’t attract him because I was lucky, but because I’ve got a lot of qualities he likes and respects and is attracted to.”

She’s quiet for a second. “Michael is bloody lovely, but [part of me] wonders if I had looked after him, would people be as interested? If I’d walked away, I would have been cold-hearted, but if he had, it would’ve been understandable.”

Having given up work to care for his girlfriend, Hoskin is now a builder and in the process of getting his helicopter licence. Pitt says she’s too busy planning her 30th birthday in July to think about a wedding, but they’re keen to start a family. She says she’ll bring up her kids according to her dad’s two rules: 1) no whingeing; and 2) no bloody whingeing.

“That’s the reason I’m so resilient,” she says. “Kids need a bit of toughness to become mentally strong. I’ll be the disciplinarian and Michael will be the favourite parent. We’ll be a great team.”

After spending the past few years challenging herself with two Ironman events, walking the Kokoda Trail, being a motivational speaker, working with the reconstructive surgery charity Interplast and creating her goal-setting initiative School of Champions, Pitt intends to devote more time to loved ones.

“Doing an Ironman was my goal from those early days in hospital, but they’re really selfish,” she says. “The last few years have been about me, so I want this year to be about being a better partner, a nicer human being, better daughter and friend.”

As she prepares for another surgery – this time on her nose – you have to wonder if she ever has bad days.

“Of course. I go through dark times. But everyone has bad days. You can let experiences destroy you or mould you. I choose to let them mould me.”

Unmasked by Turia Pitt and Bryce Corbett (Penguin Random House, $34.99) is out tomorrow.

Originally published as ‘This is how I’m going to die. It’s so unfair’: Turia Pitt’s tale of survival