The text message that destroyed an Olympic dream

THE women’s 100m freestyle final at the Rio Olympics stopped the nation for all the wrong reasons. Now Cate and Bronte Campbell finally reveal exactly what happened.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT WAS such a little thing to spark such a momentous meltdown: a text, sent by a friend back home in Australia, wishing Cate Campbell good luck in her pet event. “I’m so excited to watch you race,” he wrote. “I’ve booked out a boardroom in the office so we can all watch you.”

It flashed up about 20 hours before Cate was to compete in the women’s 100m freestyle final at the Rio Olympics, the event in which she set the world record only a month before. Until then, things were going well; she had already won gold in the relay with sister Bronte, and she was managing to block out the cacophony of expectations from home.

This friend was far from the first person to wish her luck, but there was something about that text that breached Cate’s walls. “It went from being my own moment to, ‘I have to do this for other people as well,’” the 24-year-old tells Stellar, talking about her devastation in Rio for the first time.

“I remembered this was bigger than just me. I was responsible for other people. The eldest-child syndrome kicked in. Until then I’d pushed it out of my mind — how many people would be watching me, and how many would care. I couldn’t shut down those voices after that.”

She finished sixth, in what she herself described as “possibly the greatest choke in Olympic history”. Bronte, also a medal favourite, finished fourth.

Cate still doesn’t know what time she swam in the 100m. She’s taken this year off competition. She and Bronte have never really discussed the race, but that doesn’t mean Cate has shied away from facing her demons in the past six months.

“What I’ve learnt is failure isn’t necessarily something we should be ashamed of,” she says. “It shows we have the courage to go and dare in the first place.”

“If someone went missing, it was like, ‘Cate, why weren’t you watching them?’”

To understand Cate Campbell’s story, it helps to remember that she is a big sister, the eldest of five. Her sister, Bronte, 22, is also a swimmer, and one of Cate’s best friends and biggest rivals. Her brother, Hamish, 18, has severe cerebral palsy and can’t see or speak. There’s also Jessica, 21, and Abigail, 16, who are, Cate jokes, “the two forgotten Campbells in the story”.

“Their achievements are celebrated equally,” Cate adds. “For Jessica it was completing high school, for Hamish it’s smiling in the morning, and, well, Abigail celebrates herself every day.”

The four eldest siblings were born in Malawi, a poor, landlocked country in southeastern Africa, where their South African father worked as an accountant and their mother as a nurse. Cate and Bronte would swim in Lake Malawi, where they managed to evade a rogue hippo that occasionally chomped at the humans who invaded its turf.

The family moved to Australia a few months before Abigail was born. Her parents had their hands full — mum Jenny is Hamish’s fulltime carer — so Cate helped out with her siblings.

“I’m the responsible one,” Cate says of being the eldest child. “I’m the one who’s always looking out for everyone else. If someone went missing, it was like, ‘Cate, why weren’t you watching them?’”

It’s a trait she hasn’t been able to shake in adulthood. “She does try to look after everyone,” Bronte says. “She tries to look after me a lot, which is lovely and very sweet. I don’t need looking after. At least I don’t think I do — there’s been a few moments …”

This attentiveness is a lovely, empathetic part of Cate’s character, but it didn’t do her any favours in Rio. Once that text triggered thoughts about how many people wanted her to bring home gold, she couldn’t shut them out.

“From that moment I was nervous, anxious,” she says. “I don’t blame the friend [who sent the text], as they were genuinely there to support me. They don’t even know that this message was what triggered the meltdown to come.”

Cate didn’t mention her turmoil to anyone. “Instead of seeking support, I was like, ‘No, people are my enemy, they have put me in this state.’ I went into full protector mode. I lay in bed with a racing heart, and went, ‘No, relax, just breathe.’ I was stressed that I was stressed. I should have talked it out a bit, or told someone that I wasn’t coping.”

“I was at such a high state of stress and arousal, there was static going on in my head.”

Even Bronte, the person who knows her best, didn’t notice. “I was aware she was pretty wired, as is anyone before the biggest race of your life,” she says. “I was being a bit selfish and concentrating on myself more than I was on Cate. It’s easy, with hindsight, to see the little indicators, but at the time I didn’t think it was anything beyond the ordinary.”

When Cate climbed onto the blocks the next day, her mind was betraying her. All the voices of all those people, those strangers in the street, who had said, “I can’t wait to see you win gold,” were playing on repeat.

“I was at such a high state of stress and arousal, there was static going on in my head,” she recalls. “I didn’t know how to cope with the amount of signals my brain was putting out. I was trying to focus on what to do, rather than what could happen, or who was going to be watching me. Irrational thoughts won.”

The gun fired, and Campbell panicked. For the first 25 metres of the race, she swam too fast. At the 50-metre mark, her body was flooded with lactic acid. She knew then that she’d blown it. She finished sixth. Bronte, who had battled injury all year, finished just outside the medals in fourth place.

Bronte was philosophical. She’d swum well, considering her injury. “I felt I’d given it everything.” But Cate was devastated. “After all that noise in my head, there was a resounding silence, deep and dark,” she says. “It was a very lonely place to be.”

There’s a now-iconic photo of the Campbell sisters clutching each other poolside as the bitter reality set in. They didn’t need to talk. They knew exactly how the other felt. “I was feeling so sad for Cate, that she didn’t get her moment,” Bronte says. “It’s not a nice position to be in when you have someone very disappointed and very upset. There’s nothing you can say but be there together.”

That night, they took comfort in the familiar post-swim routine: swim-down, bus ride, dinner. “Everything else was falling apart, but that stays the same,” Cate says.

“The thing about life is it goes on; you can either be a participant or a casualty.”

The 100m swim coloured the rest of Cate’s campaign in Rio. In the 50m race, a few nights later, she hesitated on the blocks and finished fifth, ahead of Bronte, who was seventh.

But in her final event of the meet, the medley relay, Cate put her individual defeats behind her and stormed home to give Australia a silver medal. It was an extraordinary feat, given how heavily she was weighed down by disappointment.

The numbers spun around in Cate’s head for months. Twenty-five metres. Eleven seconds. If only she could have those 11 seconds back, she wouldn’t have swum so fast for those first 25 metres, her body wouldn’t have been flooded with acid, she could’ve won the race.

The shock gave way to shame and embarrassment. For a while, she couldn’t look people in the eye. She felt that every time they looked at her, they saw the last few metres of the 100m race. “More than anything, I was disappointed in myself,” she says. “I’ve always prided myself on being dependable and accountable, and someone people rely on. When people were relying on me to do my job for the country, I’d let them down.”

She went to the welcome home parade with one gold (relay) rather than the hoped-for three. Cate was used to being feted for her achievements, but saw another side to the Australian public during that trip.

“For people to still be supporting me when I hadn’t won was a very humbling experience, and something I wouldn’t have noticed if I’d come back with another gold medal around my neck.”

For the first few months, she didn’t want to talk about Rio, and her friends and family didn’t force it. They loved her, victory or not, and being reminded of that began her healing process.

After a few months, Cate began the post-mortem with her family and her coach. It was tough. She still struggles to talk about it and has never watched the footage. Both Cate and Bronte have raked over what they would do differently if they had that time again.

But for Cate, Rio has overwhelmingly been a lesson in the value of failure.

“Everything I was terrified of happening happened,” she says. “The thing about life is it goes on; you can either be a participant or a casualty. I refuse to be a casualty of that first 11 seconds, I refuse to let it define me.”

For Bronte, Rio taught her to mentally cope with a body that wasn’t at its best. “It’s easy to step up on the blocks when you have done the work, and had a good prep,” she says. “It was a different experience going into Rio and not being 100 per cent, but learning to back yourself regardless.”

“I discovered who I was without this swimming angel on my shoulder.”

The Campbell sisters have made some big changes since Rio. The biggest is that Cate and Bronte no longer live together. “After Rio, we thought it was time to branch out,” says Bronte, who’s bought her first house in Brisbane. (“A swimming lifestyle is a saving lifestyle,” she says. “Unless you like buying nice clothes and wearing them around the house, you have very little to spend money on.”)

They still miss each other. “Cate used to make me coffee,” Bronte says. “Now I have to do my own. I miss her, but I see her every day.”

After the Olympics, Bronte travelled solo to Vietnam. Cate went to New Zealand and did things she’d never normally be allowed to do for fear of injury, such as skiing, bungee jumping and throwing herself out of a plane. “I discovered who I was without this swimming angel on my shoulder, whispering, ‘It’s not good to be tired and sore,’ or, ‘Don’t you think you should go to bed?’”

Bronte’s shoulder injury is under control, and next month she’ll be at the Australian Swimming Championships vying for a place in the world championship team. But she’s also learning to surf and play guitar. “I’m doing a few things I don’t have time to do in an Olympic year,” she says.

Cate’s still training but she won’t compete at this years World Championships, she’ll instead focus on the 2018 Gold Coast Commonwealth Games and will race in some World Cup events this year throughout Europe and Asia. It’s all about swim-life balance. She wants to be able to take a Saturday off to go camping, or finish a session without pushing herself so hard she vomits; in other words, she wants to live like a normal person for a while. She’ll also focus on studying — media and communications — after taking last year off university.

She’s pacing herself so she can mentally, as well as physically, be at her best for the Commonwealth Games next year on the Gold Coast and the Tokyo Olympics in 2020.

After Rio, Cate didn’t swim for almost two months. When she returned to the pool deck, the sight of the water brought on the agony and turmoil of the recent past. She felt bitter and jaded. “[But then] I dove in the water and glided,” she says. “There was this stillness and calm. I was like, ‘This is where I belong, I can still do this.’ It felt like coming home.”

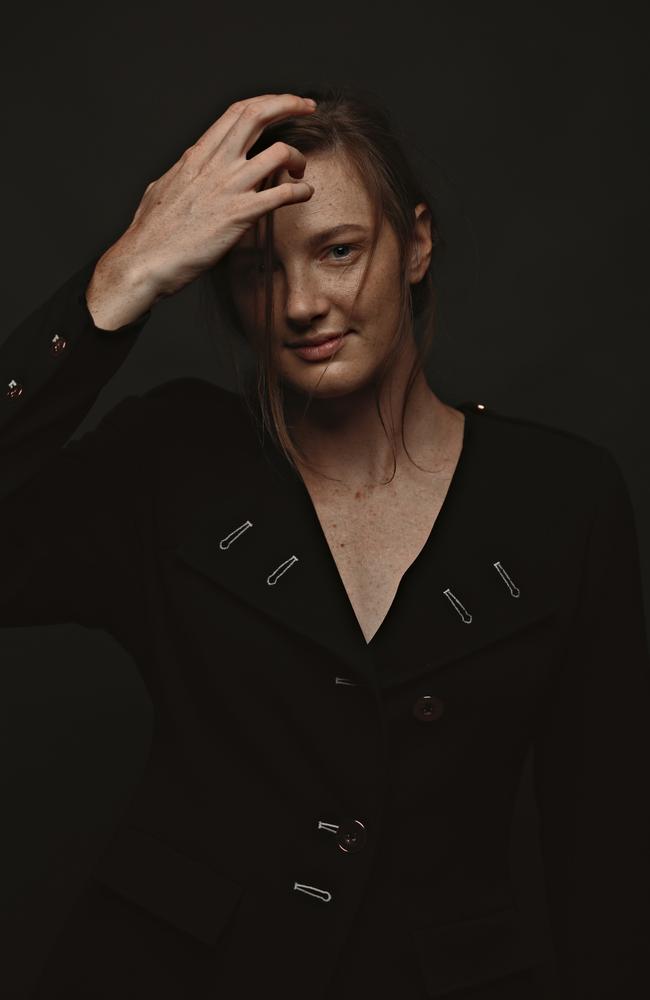

Photo: Peter Wallis

Styling: Gemma Keil

Hair & Make-up: Samantha Patrikopoulos

Originally published as The text message that destroyed an Olympic dream