Sting: Who are you calling an ageing rock star?

SHOWERED with accolades for 40 years, Sting would rather his children “think well of me” and “die with the woman I am married to still loving me” than fret about his musical legacy.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT’S AFL Grand Final day and in the depths of the MCG, Sting is putting his bandmates through their paces. Despite coming straight to the ground after a long-haul flight from his New York home, he’s looking remarkably fit and alert. His tanned face is weathered and lived in, but he looks every inch the rock star with his muscular frame clad in black boots and Balmain jeans, belying the fact he will celebrate his 65th birthday the next day.

Sting is ready to hit the ground running in front of 100,000 baying football fans as the headline act on one of the biggest days on the Australian sporting calendar. It’s no easy gig – just ask Meat Loaf – but he’s got this. In a music career spanning 40 years, 16 Grammy Awards and more than 100 million album sales, the musician has played the Super Bowl, the NBA All-Stars game and countless arenas and stadiums around the world. But even after all those years, he’s ever the perfectionist. “Let’s go again,” he says, as he launches into the opening bars of his new single.

Later, in the makeshift green room set up in the cricket nets, watching the pre-match entertainment on TV, Sting asks pointed questions about the upcoming game. Is there an offside rule? How many points for a goal? Can players get sent off?

Curiosity is a recurring theme when talking to the man born Gordon Matthew Thomas Sumner in working-class Wallsend (a suburb of the northern industrial town of Newcastle in England). And it was curiosity – and burning ambition – that inspired him to leave it, caused, in part, by a chance encounter with royalty, of all things.

The way he tells it, the late Queen Mother was visiting the shipyards at the end of his street, resplendent in a Rolls-Royce. Their eyes met and in that brief moment, a fire was lit inside him – the dream of a better life.

“I was eight years old and waving, and I caught the eye of the Queen Mother – she looked at me,” he recalls a few days later in a luxury Melbourne hotel. “And I thought, ‘I want a bigger life than the one I’m being offered here. I want to be in that car or something like it. I want to be in that ship that just goes off into the world and doesn’t come back.’ I didn’t feel I belonged there.

“There was a coal mine at one end and a shipyard at the other. Is that it? I saw those men come from work every day – I sold them newspapers. I saw how tough their lives were. [I thought] I don’t want that. I want to sing songs. I want to see the world.”

There’s a song on Sting’s newest album, 57th & 9th, his first rock release in 17 years, called “Heading South On The Great North Road”. It recalls his early years when he left his regular life as a school teacher who played in jazz bands by night, and rolled the dice to seek fame and fortune in London and beyond.

“That’s the most personal song on the record,” he says. “It’s a journey that Brian Johnson of AC/DC made, Bryan Ferry, Mark Knopfler, The Animals, me. We all had that romance of heading south. The only way you were going to change your life was to take the risk and put your gear in a van and head south. It’s a story of greasy transport cafes.”

Sting would, of course, conquer the globe as the frontman and chief songwriter for The Police, the hugely successful and famously fractious trio that released five hit albums between 1978 and 1983 and gave the world a parade of hits, including “Roxanne”, “Don’t Stand So Close To Me”, “Every Breath You Take” and “Message In A Bottle”, on its way to becoming one of the biggest bands in the world.

Their high-energy shows and spiky blend of pop, post-punk, new-wave and reggae were fuelled in part by intra-band tension, particularly between Sting and drummer Stewart Copeland, which occasionally boiled over into fisticuffs. At the height of the band’s success, Sting pulled the pin, eager for a new challenge, and the band played its last show in 1984. He’s never looked back and – apart from a hugely successful, nostalgia-driven reunion tour in 2008 (“We made sh*tloads of money and everybody was happy that Mum and Dad had got back together again for a little while”) – never felt the need to revisit that era.

“I am very proud of it and what we achieved together as a band, the three of us,” he says. “It was remarkable success over six years, and to carry on would just bring diminishing returns. The most exciting part of it all was the beginning, so I wanted to keep having new beginnings, rather than pressing the same buttons that any chimpanzee can press to get a banana. It’s boring.”

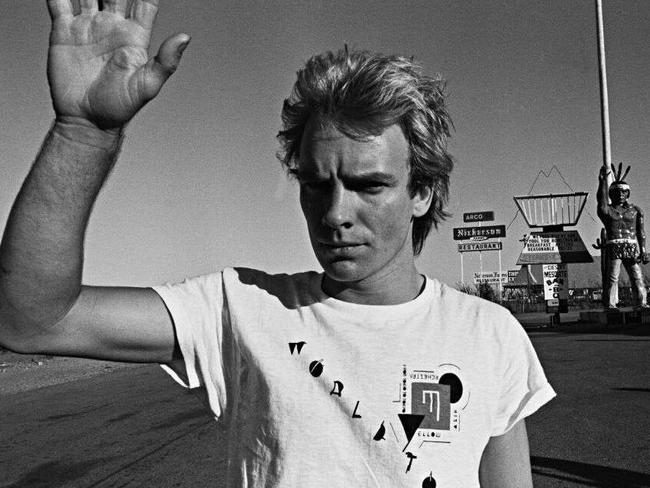

He remembers the early, lean hungry years of The Police more acutely than its stadium-conquering prime. “The start of anything is the most exciting thing,” he says. “A romance, a project, a film, an adventure… Beginnings are important.”

Legendary Australian promoter Michael Gudinski, who brokered the AFL deal and is a long-time friend, believes Sting is the most inspired and energised he has been in years. “It was the most relaxed I have seen him and I think he has realised that we all have to go sooner or later – and I hope it’s later for him,” says Gudinski. “I haven’t seen him that happy and vibed up for a while. When artists are in a good state and they want it, they deliver.”

Gudinski, whose company Frontier Touring brought The Police to Australia for the first time in 1980 and for many return visits, including the reunion tour, rates Sting as one of the most professional – and pragmatic – artists he has ever worked with.

“Years ago we wanted him to do Hey, Hey It’s Saturday and he said, ‘I’m not going on any TV show with a f*cking ostrich.’ And I said, ‘Listen mate, you’ve got all these stupid shows in England – it’s a high-rating show, it’s a fake ostrich and it’s your three and a half minutes.’ And he listened. I said, ‘It’s not about the show, it’s about your time on the show,’ so The Police did Hey, Hey It’s Saturday and it helped make for a massive album. And he said to me, ‘That wasn’t a bad ostrich.’”

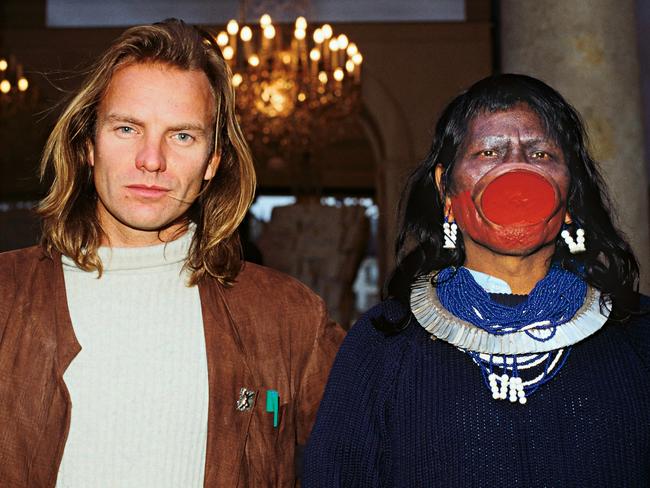

At the height of his fame, Sting became almost as well known for his extra-musical activities as for his songs. Images of him standing alongside Amazon tribesmen in his quest to save the rainforests – not to mention his throwaway line about tantric sex during a drunken interview with Bob Geldof – created in the public consciousness an image of the singer as some kind of crusading New-Ager.

“Whatever we did, we were trying to do the right thing,” he says now of the smart-alec barbs that were thrown his way. “I got a lot of flak for it, as you do, but you expect that. It doesn’t stop you though. You do something.”

When I was 26, I suddenly got this crazy, wonderful, privileged life. But it’s richer and I appreciate it more because I have had a more mundane life as well

Sting has been an activist ever since his tours on behalf of Amnesty International during the 1980s. He’s knowledgeable and passionate about politics – US presidential candidate Donald Trump, he says, is a “f*cking hoax” and Brexit is a “complete nightmare”. He still speaks with pride about the work done by the NGO he set up 27 years ago, Rainforest Fund, which pays for legal infrastructure for indigenous tribes and recently had a win in Ecuador by stopping a pipeline from illegally going through the ancestral lands. Though he lives in a New York penthouse and has houses around the world and a reported fortune of $400 million, he is very aware of his good fortune and is determined to use it to make a difference.

“It would never occur to me to somehow not be politically active,” he says. “I had a real job before I had this one. I worked in an office, I worked on building sites, I worked as a school teacher in a mining village. I paid tax, I voted, I had a kid, I had a pension plan – so I had a real life – and then when I was 26, I suddenly got this crazy, wonderful, privileged life. But it’s richer and I appreciate it more because I have had a more mundane life as well and I am grateful for it.”

Sting spent his recent mini-milestone birthday in Melbourne alone and in a reflective mood. He has already outlived his emotionally distant milkman father Ernie and hairdresser mother Audrey by more than a decade. And the deaths earlier this year of fellow rock icons David Bowie, Prince and Lemmy, as well as his dear friend actor Alan Rickman, left him contemplating his own mortality as well as inspiring the song “50,000”. Age, he says, is no barrier to activity – and it certainly beats the alternative.

Age is something that I’m not ashamed of, and I’m always very upfront about how old I am with a sense of pride

“I am always amused by the phrase ‘ageing rock star’, presumably written by an ageing journalist,” he grins. “But you either get old or you die, that’s it. Age is something that I’m not ashamed of, and I’m always very upfront about how old I am with a sense of pride and sense that you should become more sage as you get older. I mean I haven’t managed to do that yet, but it’s an ambition I have – that one day I will be sage.”

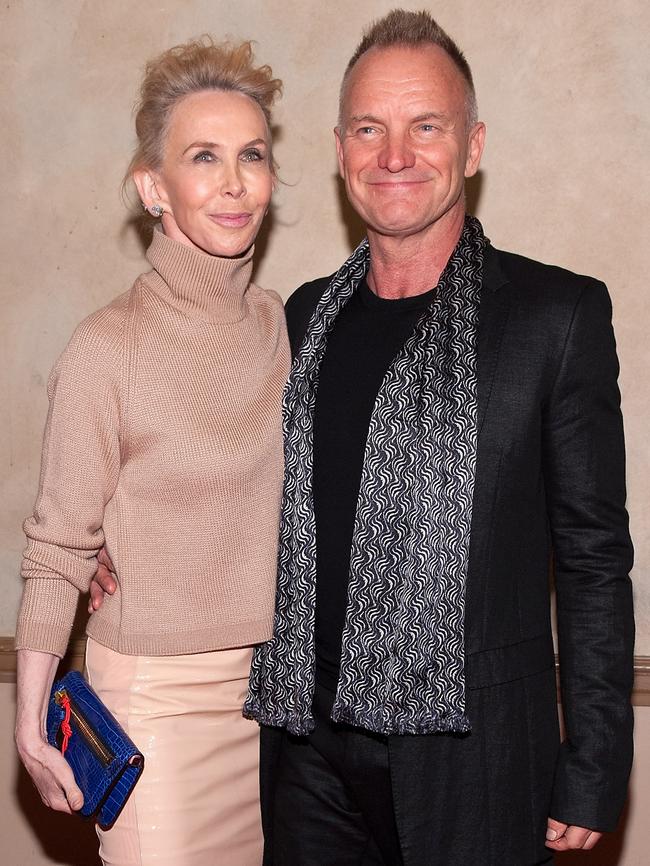

For all his success, he is entirely unconcerned with leaving a musical legacy – Sting would much rather be remembered well by his family. A father of six – he has two children, Joe and Kate, by first wife Frances Tomelty, whom he divorced in 1984, and two sons, Jake and Giacomo, and two daughters, Coco and Mickey, with his wife of 24 years, Trudie Styler.

“I want my kids to think well of me,” he says. “I would want to die with the woman I am married to still loving me, which I think is a good ambition. That’s a real ambition more than, ‘Oh, I need to have 20 more Grammys.’ Who gives a f*ck?”

Styler, an actor and producer, is “the glue of the family” and Sting concedes that the life of a family man and that of a touring musician are far from a natural fit. His children used to be mortified when he’d pick them up from school and other parents would ask for his autograph. While he’s proud of them all (“They are very well-balanced individuals, fiercely independent, hardworking, conscientious, smart, well-educated people, so I can’t have let them down that badly”), he’s equally determined they pay their own way.

“I wouldn’t want to rob them of the pleasure and satisfaction of making it on their own,” he says. “Of making a living without being given a Donald Trump nest egg. They have had a great education, they’ve lived in lovely houses and in stimulating environments, and they are out in the world. Obviously if they got into trouble I would help them, but I don’t feel like they are waiting for me to pop off so they can inherit whatever is left.”

Sting says he was recently asked who the most remarkable person he had ever met was. After decades of rubbing shoulders with actors, singers, political leaders and activists at the highest level he replied, simply: “I think I am married to her.”

“[Trudie] tells me when I am on my high horse and I need to be taken down a peg or two,” he says. “But she is also the first point of call for any creative work I do, because I know she is telling me the truth – she is not blowing smoke. And she loves me. To have that, as a man in my position, is essential. Otherwise you are spinning in space – there is no umbilical cord.”

57th & 9th is out on November 11.

Originally published as Sting: Who are you calling an ageing rock star?