ScallyWAGs and widows of the underworld

THEY fell for some of Australia’s hardest crooks. But in matters of the heart, crime doesn’t always pay, writes Andrew Rule.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

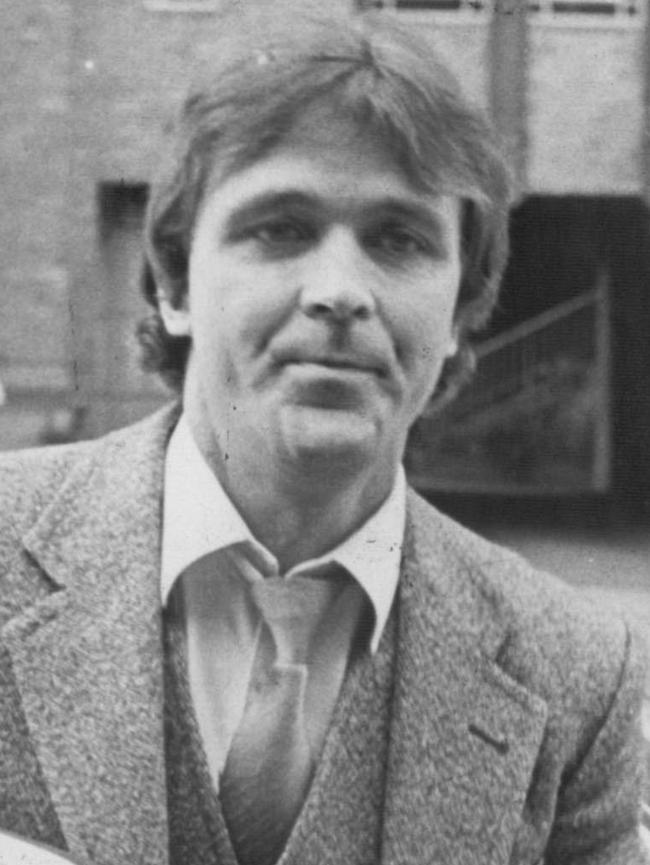

A HITMAN makes more enemies than he can kill, and Chris Flannery was no diplomat. But the man they called “Rent-a-Kill” loved his wife and she loved him. He phoned her every three hours, dependable as a well-oiled Beretta.

The day he didn’t call on time, Kath Flannery knew the worst. She immediately called George Freeman, the Sydney mobster Chris had gone to visit, and accused him of making her a widow.

They never did find the body but she was right. Freeman’s corrupt cops – reputedly led by Roger Rogerson – had proven again that those who live by the sword usually die by it.

Whether Flannery was fed to the sharks or into a sawmill incinerator on that day in 1985 is known to few – and they aren’t talking. But it was the predictably ghastly end of a genuine underworld love story.

Ray Mooney, a writer, who did time with Flannery in the 1970s, says the best thing about his jail mate was his love for Kath and desire to protect her from his dog-shoot-dog world. Mooney disputes that Mrs Rent-a-Kill relished her husband’s murderous ways. The same can’t be said for other gangsters’ women.

Sportsmen have WAGs; crooks have scallyWAGS. Enough of them to fill prison visiting rooms every week: proof that, in matters of the heart, hope often trumps experience.

The Mokbel women have seen the highs and lows of marrying mobsters. For a decade they lived in a fool’s paradise where cash gushed like an endless jackpot. But putting a nose in that trough meant getting dirty.

Back in the late 1990s, when “Fat Tony” (Tony Mokbel) was handling more black money than a Swiss bank, he had as many strippers on the payroll as he did jockeys, trainers, bookies and prison officers.

Why would any sane woman marry a mobster? Even if a few crooks are suave, handsome and rich, most are also violent, ruthless and unfaithful.

One night, Mokbel invited them all, including Carl Williams, back to one of his properties and locked the gates so guests and strippers could party undisturbed. The host didn’t want any wives cramping their style but his sister-in-law had other ideas.

The party was going strong when Milad Mokbel’s wife, Renate, scrambled over a fence and attacked the nearest strippers. “It’s on, it’s on!” a delighted Williams chortled as the furious woman hurled punches and abuse.

Renate was no “doormat” – unlike Tony Mokbel’s wife, Carmel, who lived a retiring life while hubby built a drug cartel. She did as she was told, such as being a nominal owner of a string of racehorses as a front for Mokbel. Her reward was to be humiliated as Mokbel took other women. Among them was rumoured to be criminal lawyer Zarah Garde-Wilson (when asked openly in court about an “on-off sexual relationship” with Mokbel, Garde-Wilson asked her counsel to object on the grounds of relevance).

Another was serial gangster consort Danielle McGuire, who would meet Mokbel in Greece (and have his baby there) after he fled Australia hidden on a boat in 2006.

After Mokbel was captured and subsequently returned to Australia to face prison, McGuire took up with another gangster, outlaw motorcycle boss Toby Mitchell.

The enigmatic Garde-Wilson was already notorious in legal circles because of her relationship with convicted killer Lewis Caine.

After Caine’s murder in 2004, she took action to remove sperm from his body in the hope of impregnating herself. Caine was no cashed-up crime czar and had nothing to leave except his DNA, so wanting his child wasn’t about money.

Garde-Wilson, dubbed the “hyphen with the python” for the snake she kept in her chambers, came from a distinguished establishment family.

She had grown up on the family grazing property in New England, went to boarding school and was an outstanding law graduate.

McGuire, by contrast, was raised to be a gangster’s moll; her mother lived with callous killer Rodney Collins, in suburbs of Melbourne that most lawyers would drive through with the doors locked.

Notionally a hairdresser, McGuire always had men to supply her with clothes, jewellery and anything else she fancied.

In her 20s, she mostly fancied drugs, which led to jail time – and to an affair with drug dealer Mark Moran, the first man down after Williams declared war in 1999.

McGuire, the crime groupie, had a leg in each camp, given she moved from Moran to Mokbel.

The cool lawyer and hard hairdresser were from different worlds, but they had something in common besides shapely figures: both were involved with the Lebanese pizza-maker-turned-drug-dealer, whose main asset was unlimited illicit cash.

Mokbel the millionaire punter must have suspected that if he’d been a penniless postman, the odds of Garde-Wilson and McGuire going for him would be 1000-1 and drifting.

So what is it with women and gangsters? Apart from money, that is.

Most mobsters live fast and die young – and the survivors often die broke or in jail. Not a great recipe for a happy marriage, but that has never stopped women looking for Mr Wrong. Prudence, logic and the law run well behind lust, cheap thrills – and sometimes love. And the best of these love stories isn’t about trashy crime groupies chasing money and 15 minutes of fame.

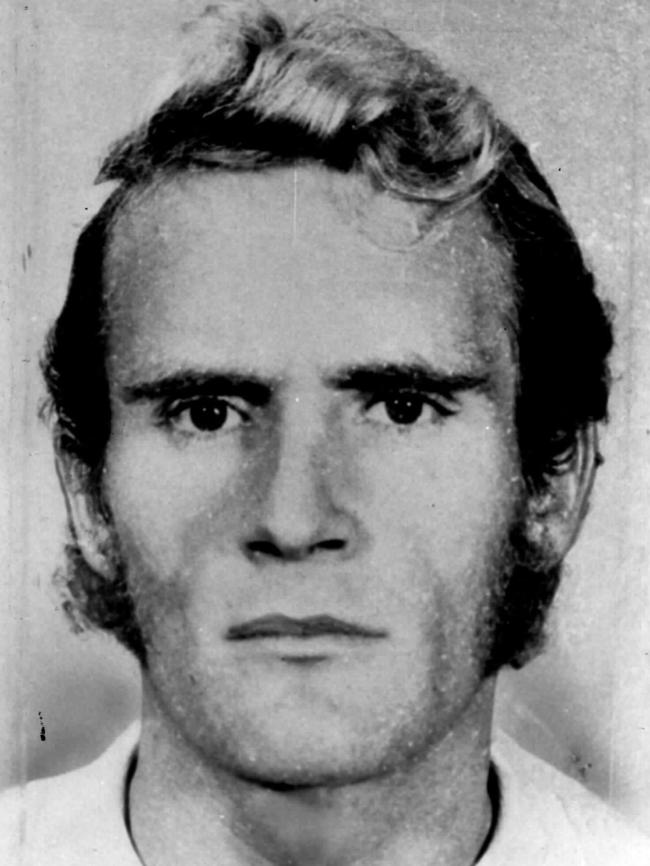

It’s about the fugitive armed robber Russell “Mad Dog” Cox and his longtime lover Helen Deane, who shared 11 years on the run together. Deane spirited a wounded Cox into NSW after a gunfight with a Melbourne robber in 1983, persuading a country doctor that her husband had survived a shooting accident in Papua New Guinea, and had returned by light plane rather than risk treatment there.

After Cox – real name Timothy Melville Schnitzerling – was arrested following a shootout at a Melbourne shopping centre in 1988, Deane tried to smuggle a pen pistol to him in court.

She visited him religiously in prison and they were married before his release in 2004. Mr and Mrs Schnitzerling refused all offers of interviews and have lived quietly ever after in Queensland.

Still, why would any sane woman marry a mobster? Even if a few crooks are suave, handsome and rich, most are also violent, ruthless and unfaithful.

Some just want to star in their own soap opera. “Famous, infamous, it’s all the same,” Roberta Williams once said. She’d know, having attached herself to Carl Williams in 1997, when he started spending buckets of drug money.

The gangster life killed Williams, but made his wife a member of the most exclusive set in town – the first-name club. Her character became part of the cultural lexicon after being played for laughs – and raunchy sex – by Kat Stewart in the first Underbelly TV series.

The fictitious Roberta meant the real one became a fixture in gossip columns and news bulletins. When her former father-in-law George Williams died this year, cameras were following her. For a Frankston street kid, that’s celebrity.

Besides looking for love in all the wrong places, there’s the pull of “easy money”. Some are totally motivated by it; others discreetly turn a blind eye to unexplained income.

Roberta Mercieca was the youngest of eight children born to a Maltese migrant truck driver and his wife. When she was young, her father died in a burning truck – a start to life a defence lawyer might use to paint a sad picture of a fatherless girl, neglected and roaming the streets. But her older sister, Susan, doesn’t buy it. She calls Roberta a mercenary liar who “doesn’t care who she hurts or where she gets it from”.

Roberta hooked up with a friend of the Morans, Dean Stephens, at 16. He fathered her first baby, Tye, then two more. After big spender Williams lured Roberta away, Stephens belted him in public, which means he is one of the few known survivors of the war Williams started soon after.

Hostility over Roberta’s affections was at least part of the reason behind the showdown between Williams and the Moran brothers, Jason and Mark. Of course, money and drug matters also led to the confrontation in 1999. But without the added drama over Roberta, the vendetta might have faded without fatalities.

If Roberta had pushed Williams in his campaign to exterminate the Moran crew, it would fit what psychologists have called the “Lady Macbeth” syndrome. Like her one-time enemy Judith Moran, Roberta wouldn’t know Lady Macbeth from a Big Mac. But those two women from opposing camps have much in common with each other and Shakespeare’s arch manipulator. They want the power and influence that comes with money – unlike docile doormat wives associated with ethnic crime groups that treat women as inferiors, but shield them from criminal activity.

Then there are the straight-out risk-takers, who get a thrill out of sharing beds and crimes with dangerous men – the Bonnie and Clyde fantasy that Hollywood turned into a legend.

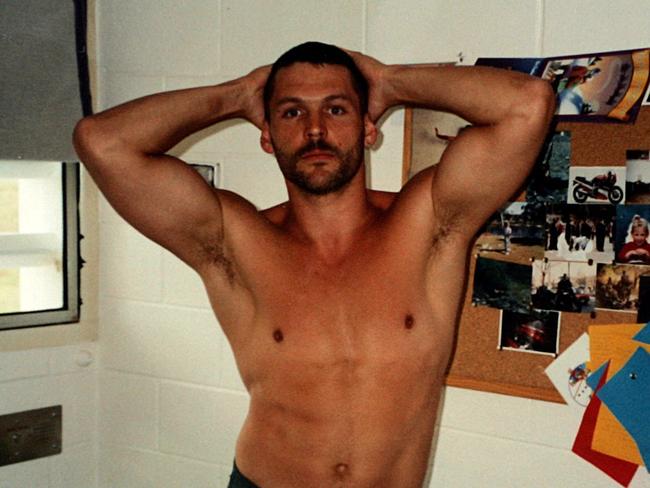

When crazed robber and serial escaper Chris “Badness” Binse met his bisexual girlfriend Roxy* in 1991, she was a professional shoplifter. She taught him shop stealing; he taught her to drive getaway cars in armed robberies.

In 1992, she helped him pull off maybe his most audacious escape – from Parramatta jail. It didn’t last: Binse is facing a long term in prison and Roxy a long time living under assumed names, which hasn’t stopped her from submitting pictures of herself to a soft porn magazine.

Roxy is a long way from the “Florence Nightingales” who graduate from rescuing birds and other animals, to “wounded” jailbirds. Among these are damaged women, perhaps abused as children, who cultivate men in prison, seeking protectors who, they fantasise, will shield them from danger or avenge past wrongs.

Besides looking for love in all the wrong places, there’s the pull of “easy money”. Some are totally motivated by it; others discreetly turn a blind eye to unexplained income. Some stay in dangerous relationships because the cash and excitement are hard to give up in circles where “hot” clothes, jewellery and luxuries are one-third retail.

Even when Judith Moran – then Brooks – was a teenage dancer for the Nine Network in the 1960s, she ran with known thieves, received stolen goods and lusted after gunmen. The father of her oldest son, Mark, was Les Cole, shot dead in Sydney in 1982. She switched to Lewis Moran, not as dashing as Cole but just as nasty.

A lawyer once saw Moran punch Judith so hard he knocked her out. But she was no better – bashing other women and threatening people with her ultra-violent sons Mark and Jason.

Lewis Moran referred to Judith as “an imbecile” and never married her, but she took his name and played the gangland widow until she was jailed for plotting the murder of her brother-in-law, having outlived two murdered sons and their fathers. Some would say she brought it on herself.

Unlike Judith, neither of late Mark “Chopper” Read’s wives wanted to be crooks when they married the self-described “no-eared psychopath”. The teenage Margaret Cassar had known the young Mark Read in Melbourne’s northern suburbs. She worked a day job for years while waiting for him to get out of jail, then moved to Tasmania with him. But she lost faith when he mixed gunplay and liquor and shot a bikie friend – possibly accidentally – and subsequently went back to jail.

Read would later claim that his barrister suggested he marry a “nice Tasmanian girl” to help with his parole. If that’s true, it worked. Mary Ann Hodge, a farmer’s daughter brought up as a Seventh-Day Adventist, read Read’s memoir and visited him in jail because he, too, had been raised as an Adventist. Soon after marrying her, Read was released and worked on the Hodge family property. They had a son just before the film Chopper made him an unlikely celebrity.

On a trip to Melbourne, Read rekindled his first love, left Mary Ann, and married the patient Margaret… who just happened to own a house near a pub – far from farm work in a cold climate. For a crook, that’s wedded bliss.

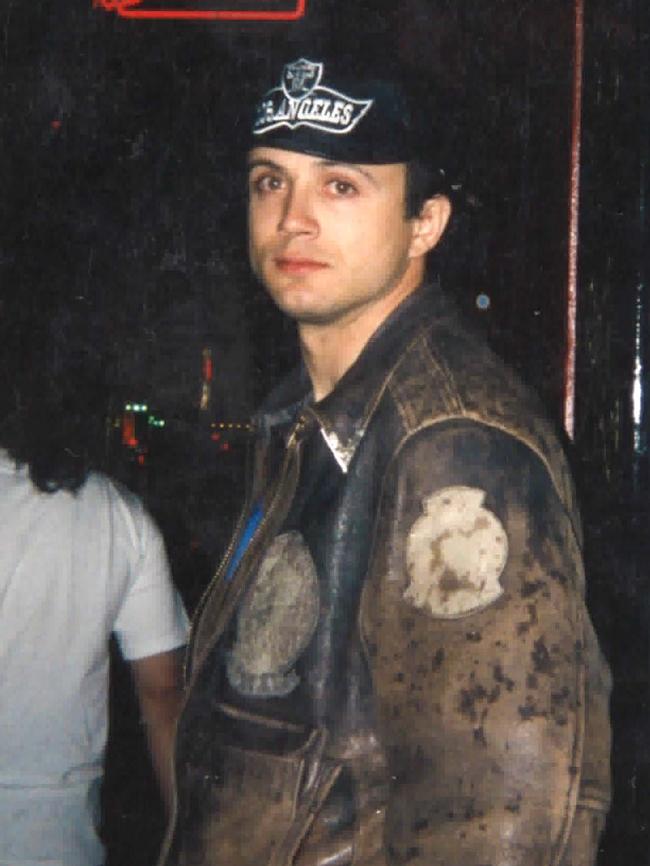

One gangster girlfriend who has stared down disgrace is Karen Soich, now a leading Auckland lawyer. As a young law clerk Soich caught the evil eye of global drug trafficker Terrence Clark in the 1970s. Before Clark’s arrest for murder, he photographed her rolling naked on a bed of bank notes, a professional faux pas that stopped her getting her practising certificate until 1991.

These days, Soich keeps quiet about the good old, bad old days with her killer lover. But her firm’s website spruiks her with the line, “Who’s right, who’s wrong, when love is gone?” She’s the expert.

Originally published as ScallyWAGs and widows of the underworld