Romance novelist Rachael Treasure’s dramatic real-life story

REAL life has been a dramatic tale for top-selling romance novelist Rachael Treasure.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

RACHAEL Treasure is giddy with excitement. Her 13-year-old daughter Rosie has just cantered on a horse for the first time. “I’m a bit emotional,” she says, from her small rented home in the pretty village of Richmond, 25km north-east of Hobart in Tasmania’s Coal River Valley.

Rosie is Treasure’s eldest child and has mild cerebral palsy, which restricts her mobility and delays learning, so the canter is a milestone.

It also edges Rosie closer to her dream of making the Australian Paralympic Equestrian Team one day. “Just a small goal there,” laughs Treasure, one of the nation’s best-loved romance novelists. “Rosie is one of those kids who has sunshine in her – she’s the happiest little girl, and has more get-up-and-go than any child I know.”

The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. When not being mum to Rosie and Charlie, 11, and caretaker to two kelpies, countless chickens, one tubby pony and a neurotic toy poodle, Treasure is busy writing. “I write everywhere – in the ute waiting to pick up the kids from school, in my local cafe, everywhere but sitting at a desk,” she says.

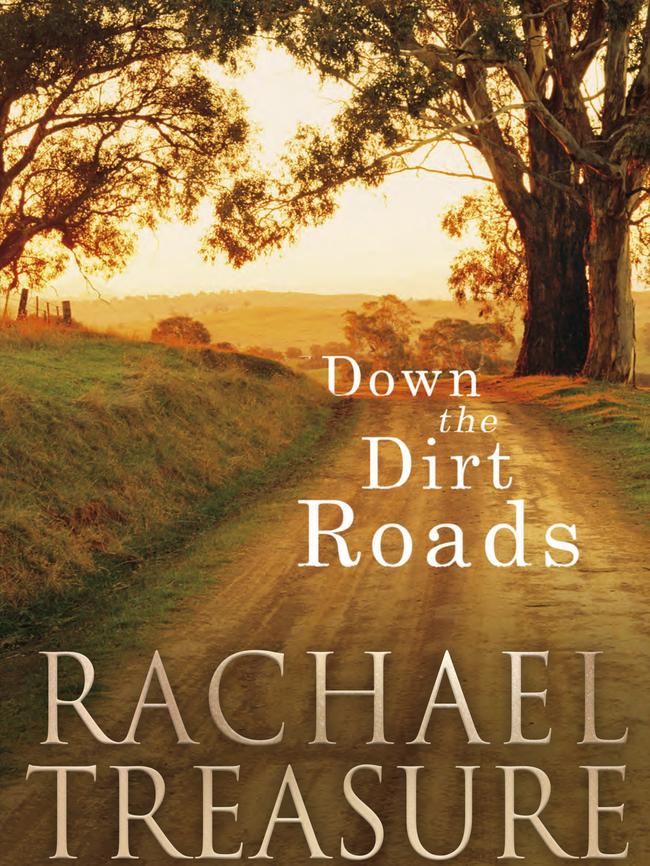

Treasure is a pioneer of the “chook lit” genre – think “chick lit”, but instead of heroines sipping champagne and shopping in Manolo Blahniks, they’re downing rum and mustering in R.M. Williams boots. Her latest book, Down The Dirt Roads, has just been released, but unlike her other novels – including Jillaroo, The Cattleman’s Daughter, The Farmer’s Wife and, wait for it, Fifty Bales Of Hay – it’s a different kind of love story.

Down The Dirt Roads is about Treasure’s romance with the land. It’s part memoir, part guide to gentler farming and, like all good plots, is peppered with heartache, avarice and loss. “Never in my wildest imaginings of my adult future did I think I’d be in my 40s, living in a rental property, in a town with my children… farmless,” she writes in the introduction. “But there it was: the bare, brutal facts of a failed dream that a country girl like me had to face… I no longer had a future exploring the same blissful bushland with my children that had seeped into my own soul when I was a child. I no longer had a life of teaching them about caretaking animals and soils, things that I not only loved, but revered and worshipped.

“The story of how I lost that future and my farm is more far-fetched than any novel I could dream up. But life’s like that. It takes you down roads you never expect to go down, under circumstances that are, at times, stranger than outback fiction and harder to swallow than a John Deere 24-plate disc plough.”

The story of how I lost that future and my farm is more far-fetched than any novel I could dream up

Those circumstances are ones Treasure is willing to discuss in broad terms, but not specifics. Out of respect for her father and brother, she doesn’t name them in the book, nor does she mention her ex-husband by name.

Simply put, after she divorced in 2010, her father gave the family farm to her ex-husband. “I don’t blame anyone; I am coming from a place of healing,” she says.

It has taken more than five years for Treasure to arrive at this position of peace and forgiveness. “The bottom line is, Dad was getting old and – again, no blame – he’s the product of an era where men are the hub, the centre of the wheel. So, in 2011, he opted to keep my ex-husband on as partner and my older brother, who is not a farmer, so we moved on.”

In what seemed like a blink after four decades on the family farm, Treasure, her kids and tribe of animals were homeless. Penniless, too. “People think if you’re a best-selling author that you’re flying a helicopter – my first four books were the most profitable, but the money all went into farming infrastructure,” she says. “As a novelist, you have to be very frugal – even now I forage around the garden for chook eggs.”

At 47, Treasure finally feels free of the bonds of expectation. “I was raised to put up, shut up and accept, like a good Tasmanian woman,” she says. “I disempowered myself all my life, thinking I was less – but losing the farm turned out to be the best thing as it made me think, ‘Hang on, if I don’t say anything, then I won’t change anything for my daughter or daughter-in-law.’”

With the gentleness of hindsight, it’s clear Treasure was destined to break the mould. Her turbulent adolescent years were spent at an unnamed private school in Hobart which “felt like a prison” and “didn’t encourage women to come into their feminist power, but strive to be nice ladies for husbands or get into the man’s world of universities”.

I was raised to put up, shut up and accept, like a good Tasmanian woman. I disempowered myself all my life

Treasure chose the latter option and gained a bachelor of communication at Charles Sturt University in Bathurst. Working as a rural broadcast journalist in the mid-1990s, she met teacher John Treasure and “fell head over heels in love”. The couple dated for seven years, enjoying “the most brilliant times in Gippsland”, where his family had been grazing the Victorian high plains since the late 1800s. “They were the golden years,” says Treasure. “Then it went like so many marriages – you can never fulfil someone else’s need. I trusted that people do have the fairytale thing; that was the blissful ignorance in me.”

She won’t be drawn on the precise reasons for the split, but insists “men would have a better time on this planet if women learnt to stand up in their power and reach self-awareness”. One thing she will discuss is how hard it was trying to facilitate change on a farm that was “very much in masculine hands”.

“What I could see from my 30 years in agriculture was that machinery had become bigger, and we had gone down a path of corporations owning all of these products and owning 95 per cent of the world feed bank,” she says. “My feminine perspective is that it’s all about love and nurturing. [But] we have been raping the soil instead of protecting it.”

Treasure rejected traditional fertilisation methods and advocated the “pasture cropping” alternative developed by NSW farmer Colin Seis, which relies on restoring native grass cover. “I’d say to Dad, ‘Could we NOT order another load of [fertiliser] superphosphate?’ It was subsidised by the government for years, but kills the very fungi that’s under the soil that feeds plants. But sure enough, another truck would turn up.”

After leaving behind the “dark times” on the farm, Treasure studied Seis’s technique and is now part of a “revolution in how food is produced”.

“I want people to be aware of what they are buying from the supermarket – those vegies are sprayed numerous times before they’re put in their kids’ meals,” she says. “We as consumers hold all the power, but we don’t realise it, and I’d love conventional farmers to realise that there is a dollar in this if they farm in a more ecological, supportive way.”

Treasure – whose résumé also includes working-dog handler, stock-camp cook, wool classer and drover – hopes Down The Dirt Roads will convey a multi-layered message: farmers can be more profitable; women can enrich the lives of others if they enrich themselves; and Mother Nature can benefit as a result.

At the time of this interview, Treasure is waiting to hear if her offer on a house with eight hectares outside Hobart has been accepted – it has kennels for training working dogs, also one of her son’s passions, and room for horses for her daughter. “I can teach both children my love for working animals, quietly and calmly,” says Treasure. “We’ll have a few sheep and grow vegetables, and it will be a hub for weary farm women so we can have weekend get-togethers, do yoga, chat and grow grassland.”

My beloved... will not be a knight in shining armour but a fully whole, caring and loving person who can reflect who I am

So is there space in the full life of this “chook lit” queen for romance of her own? “I’ve never seen a functioning relationship that is warm and loving and caring, so until I learn to be that to myself, I’m not going to inflict that on someone,” she says. “My beloved, as the kids call him, will arrive and we have no idea who he is, but he will not be a knight in shining armour but a fully whole, caring and loving person who can reflect who I am.”

On her path to “reclaiming inner power”, Treasure meditates daily, does yoga and keeps a journal. “I write three pages every day. For the first six months after leaving the farm, I was repeating the same negative pattern, but I decided that story was getting old. So I have rewritten the narrative of my life,” she says. “I’m not blaming those blokes anymore that the dice has landed this way. I am grateful for my doona, for the dog snoring and farting under the bed, for the mess the kids left the night before because that means we had fun.

“That’s not to say I don’t fall over sometimes, but I’ve learnt that if you count everything as a lesson then nothing is wasted.”

Originally published as Romance novelist Rachael Treasure’s dramatic real-life story