The untold story of Jimmy Barnes’ harrowing childhood

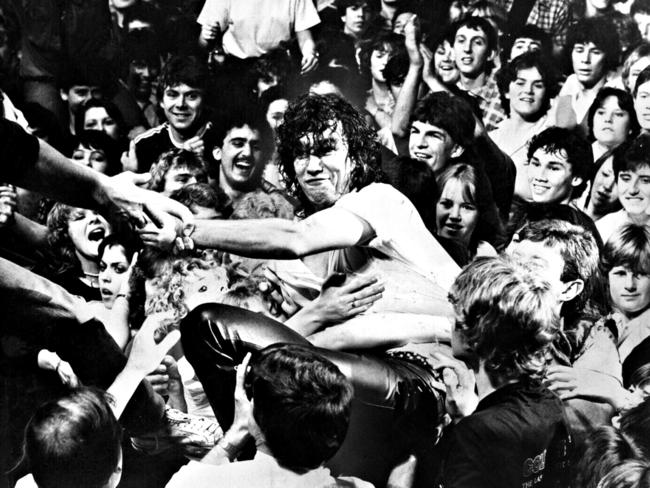

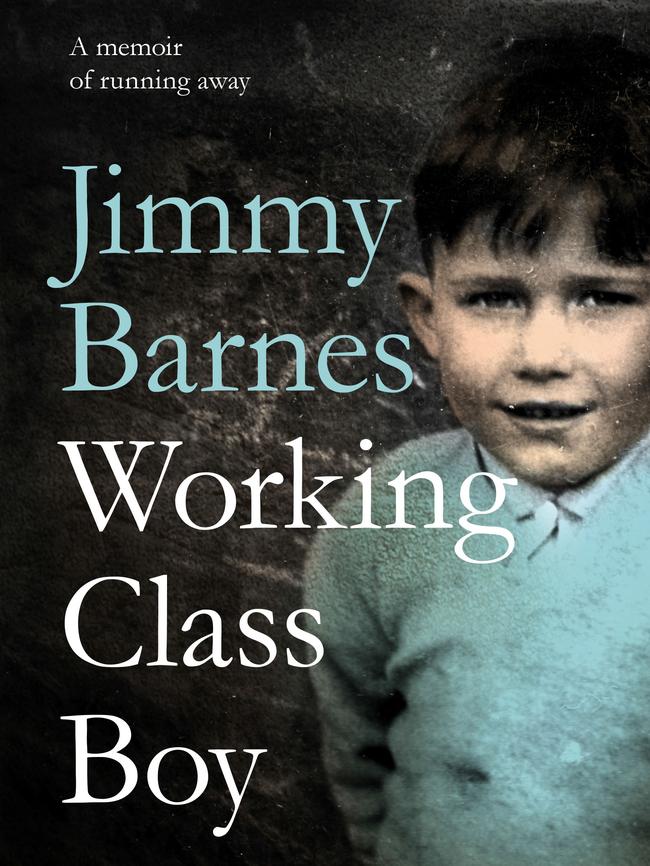

AHEAD of the release of his memoir, rock star Jimmy Barnes has spoken for the first time to his own son, David Campbell, about his often-shocking family history and the harrowing recollections in his book.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE mood was already a highly charged emotional one when Jimmy Barnes sat down last month to be interviewed by his son, David Campbell, for Stellar.

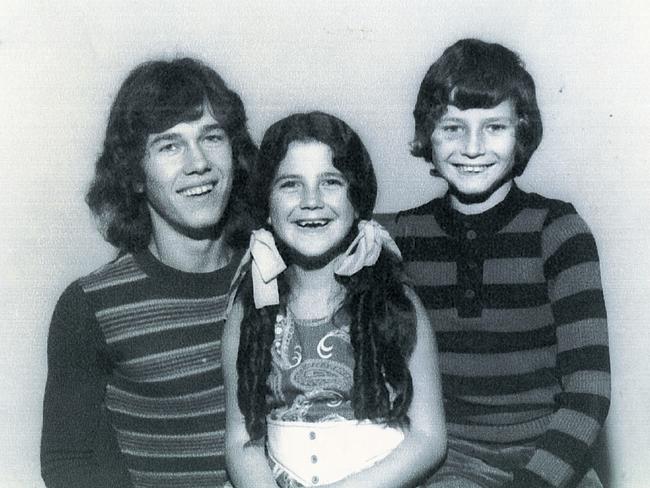

Earlier that week, the 60-year-old had lost his mother, Dorothy – a woman who plays a leading role in her son’s upcoming book, Working Class Boy, in which the legendary rock star reveals the desperation and violence he experienced while growing up.

Speaking to his son for the first time about the often-shocking family history, and harrowing recollections he writes about in the book, had both men breaking down at times.

But while Barnes tells Campbell of the difficulty in committing his pain to paper and being on the brink of sharing his story with the world, he is adamant it is a story that needs to be told.

David Campbell: How are you feeling about the release of your new book, Working Class Boy?

Jimmy Barnes: Imagine the dilemmas I’ve had before everybody reads it, all the family. It’s in production now. I can’t change it. They gave it to me to do the last read and the last edit while my mum was on her deathbed… I wanted to change stuff, but I just said, “No, I’m not going to read it again.”

It’s been an intense time. Your mum died, and we’re talking about a book that is really all about your parents and the effect they had on your life. How does it feel knowing all this is going to be out there soon?

It’s strange, because I’ve been wrestling with how I was going to let them read it. I make it clear at the start that this is purely my way of looking at life and what I’ve seen from my eyes.

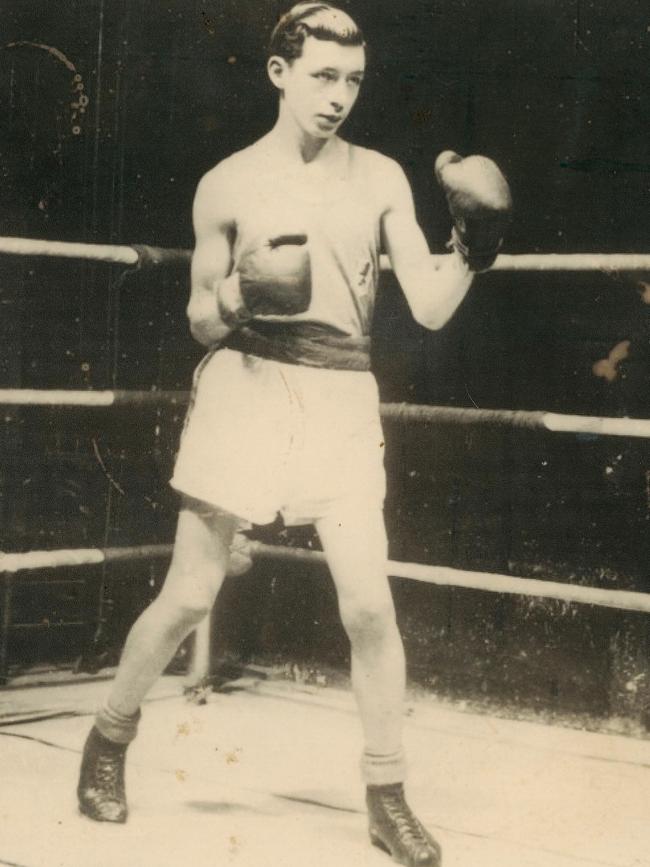

The book starts in Glasgow, where you were born. What do you remember about your time there?

I remember all the stuff from Glasgow, and I was five when I left. I can even remember the house I was born in, and we moved out of that before I was 10 months old. I’ve drawn pictures of it. Of course, I’ve spoken to therapists about it and they reckon that memory at that early age is normally due to trauma. So there was probably violence in the house. I remember the smells and streets in Glasgow. I remember the sense of fear all the time, and the cold. We lived in these tenements, these slums, which are now trendy inner-city dwellings in Glasgow. They had about eight apartments in them, and one toilet downstairs in the entrance foyer, [called] the close. It was filthy. I was terrified of going down there; you couldn’t go at night because the lights were always smashed. One of my sisters was attacked in the close and it was quite serious. That was when we were four or five.

There’s a story in the book about you and one of your mates getting taken by the gang in the next street and being belted with rocks.

We both got belted with rocks. But then they were going to throw bottles and I ran like hell. They told me to run, and I ran. And he froze. They literally cut him up. I think they cut his wrists and set fire to this shed he was in and left him in it. He was really badly burnt and ended up in hospital. You couldn’t go out of your street without your family with you. Kids were just brutal and violent.

I remembered the kids, my sisters, hiding my mum under a bed, battered and bruised, so my dad couldn’t find her. My dad was a quiet assassin.

And then alcohol is added to that. Booze is on every page in this book. It’s like a main character.

There was a lot of drinking. Everybody we knew drank, and they drank way too f*cking much. My mum tried to make ends meet and battled with my alcoholic father who would drink away all the money.

To know that alcoholism was in the family was interesting. Here was a guy, your dad, who would get all the money and then go to the pub and drink it all away.

And he’d be looking at Mum to feel sorry for him. “Oh, I really f*cked up.” And this happened from Scotland through to when he left when I was 11. He did that all the time; he would come back and he was really sorry. And he’d work really hard and try really hard. Then he’d get money and he’d just go crazy. He gambled, too.

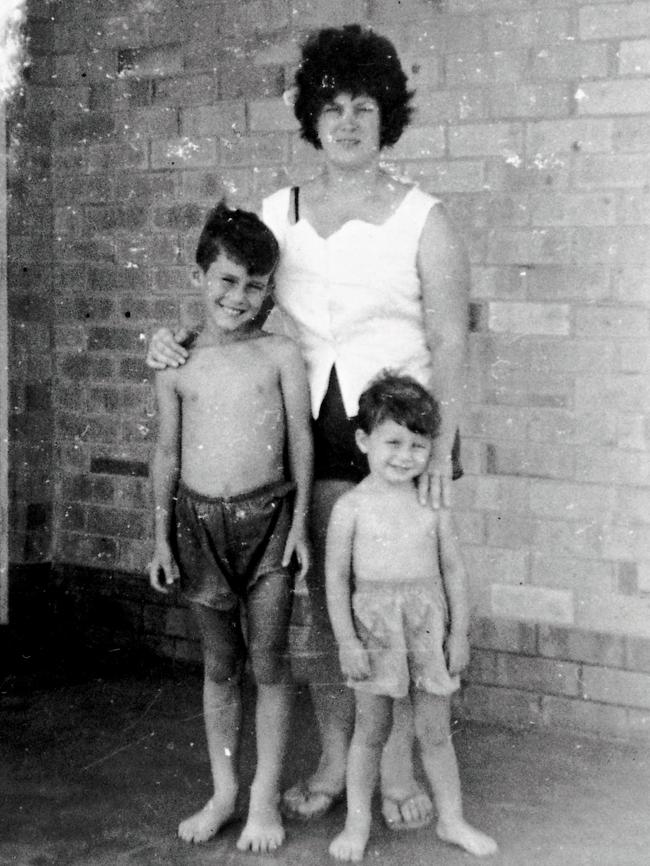

When you [and your family] moved to Australia, everybody thought it would be the solution to their problems, when really they just brought their problems with them.

You’d think it wouldn’t happen in Australia but, really, it got worse here because they had no back-up. My family has all these womanising and alcohol and violence problems in Scotland. And my mum thought we could simply run off and get away from it all. Of course, all of it transferred. Mum had no one to run to. She had no one to go to when she’d been bashed or when we were hungry. She was on her own. It literally got more and more desperate the further we got from Glasgow.

One of the issues you touch on in the book, although you don’t go too deeply into it, is domestic violence in the home.

A lot of domestic violence in the home. It’s one of the things that unfolded to me as I was writing the book. I never really, as a young man, remembered much of my dad hitting my mum. I just thought my mum was violent.

Because she was defending herself.

She was defending herself. As I was writing the book, I remembered the kids, my sisters, hiding my mum under a bed, battered and bruised, so my dad couldn’t find her. My dad was a quiet assassin. He was really charming and smiley and softly spoken, but he could knock you out in a second. And he did the same to my mum. It was always fuelled by alcohol – alcohol, fear and ignorance – just desperation, really.

I remember just being afraid constantly. I’ve been afraid since I was born, really. But when my mum left, it was this whole different degree of fear

It’s a big deal when your mother leaves in the book. Even by today’s standards, a mother leaving her family is a shocking thing. You were very close to her, so it must have been devastating.

I was really close to her; I was a mummy’s boy. I think I was about eight years old when she left, so I was really closely bonded to her. The only time I ever felt safe in the world was when I was near her, in her arms. So, when she left, I couldn’t believe it. I used to think we were a normal family, that the behaviour in our house was normal, so I didn’t expect her to disappear. I just thought, “They’ve got problems; they’ll work through them. We’ll be OK. Everything’s great. Everybody loves each other.” As kids do. So when I woke up that day and she was gone, it was like the whole rug had been pulled out from under my life. I was sitting there, waiting for her to come back. My dad would just drink and cry. He got depressed. He didn’t want her to go, either. I think it was a shock to him. He didn’t expect her to walk out. Instead of strengthening him and making him look after us, he just fell apart even more.

So who looked after you?

[My sister] Dot. She was three years older than me. So she was 11 and she became the mother, because my dad was never there. Dot would literally steal money from him so she could feed us. I remember we lived forever on chips. The odd egg here and there. But it was OK because we liked chips [laughs]. I remember just being afraid constantly. I’ve been afraid since I was born, really. But when my mum left, it was this whole different degree of fear. I was waiting for the world to collapse on us. We were all the same.

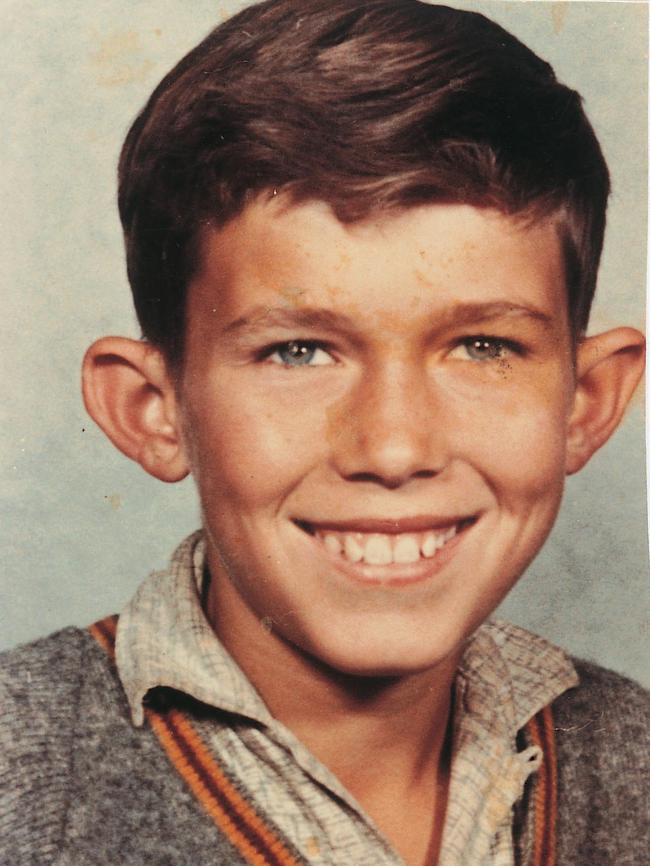

I want to talk about some of the close calls. A couple of them are really the worst things you could ever think of. You were hitchhiking and getting in cars with people you didn’t know, who could have easily taken advantage of you.

Oh yeah. I had someone looking out for me the whole time. As bad as it sounds, I think I was lucky. Either I had really good survival instincts, or there was somebody out there looking after me.

There was an incident where you saw a woman being gang raped.

I toned that down [in the book], but I remember it so vividly. I was stunned. I was nine years old or something and remember seeing this going on, but I didn’t know what the f*ck it was. They reminded me of a pack of dogs. It reminded me of animals. I just thought, sh*t. But nothing happened. [The men] ended up walking around and the girl just hung around with them. It was kind of normal. That was sort of my introduction to sex. It was a horrible thing. But I knew people who were involved in it, so that made it worse.

There was also an incident when your mate was in the bedroom with his brother…

I remember I used to stay out of the house, because it felt safer to be out of my home than it was to be there. When I stayed at my mate’s place it was all fine, until his brother got out of jail… I remember this guy trying to f*ck me. I freaked out and climbed out of the window. And he just sort of rolled over and tried to shag his brother. His young brother. We were kids. He got out of jail for some violent crime. I knew the whole family, they were all mates of the family and my parents. It was a weird thing.

One of the most important parts about the book is to share the experience, because there are people out there right now going through the same thing

Do you think people are ready to read about all of this?

I thought my childhood was really normal. But when I started writing about it, I realised it was really f*cking abnormal. But the saddest part was, by the end of it, by the time I finished writing the book, I started to realise that it’s probably more normal than we think. That’s why, for me, one of the most important parts about the book is to share the experience, because there are people out there right now going through the same thing, and probably more than when I was young.

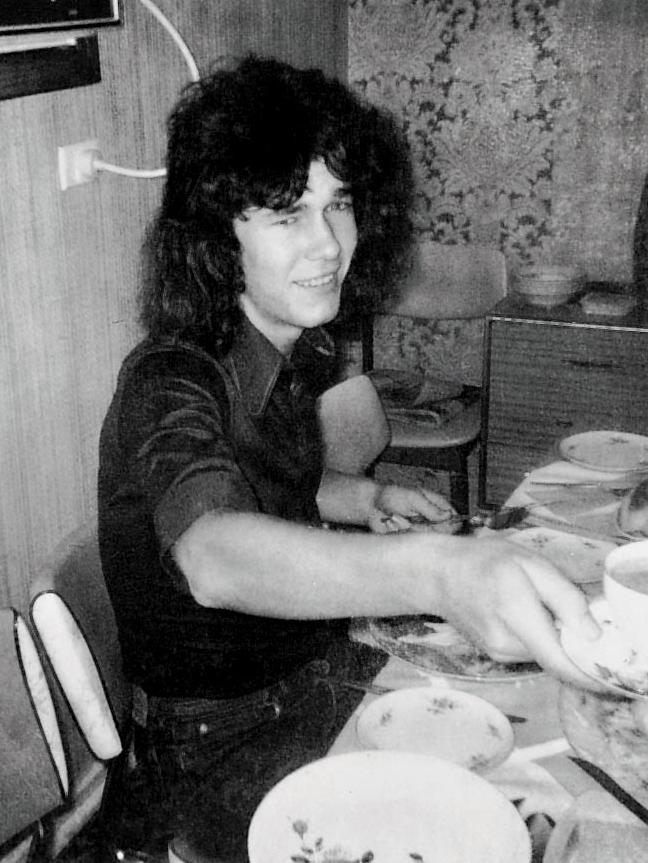

Over the years, I’ve had ups and downs about how we’re related [Campbell was raised by his maternal grandmother, Joan, and didn’t know Jimmy was his father until he was around 10 years old]. I’ve pulled back and I have come in. I’ve done therapy… but the book made it so clear to me, [in that] I actually understood the exact train of how you got to where I was conceived, where I was born and what you did post that. I had more clarity reading those chapters than I have in my whole life. It’s almost like a present.

I can’t speak for them, but your mum probably came from the same things as me – if not worse. I was very fond of your mum; I thought she was a really lovely girl. We were like kindred spirits. We weren’t madly attracted to each other; we weren’t going out. We would just hang on to each other in the night. When I first heard that your mum was pregnant with you, it was probably the most terrified I’d ever been in my life. Not just because of the repercussions of it, but being responsible for bringing someone into this world: “Why the f*ck would I want to bring someone into this world? I can’t even stand looking at myself in the mirror.” So, it was a huge thing.

Absolutely. But you say that if you could go back and spend every minute with me, you would. And that made the book for me. It really did. That gave me, as a human, as your son, such closure.

But can you imagine that now with your own son? Not having that time with him? It’s such a loss for everyone. And you can’t replace that time. You can’t make it up. So the relationship is different. It’s totally different, but it starts from simply trying to be there and trying to be understanding of that. I couldn’t come and sort of gush and force myself on you, because it’s always been very measured.

I think it’s really important that this book is just about the first 17 years of your life. God, I felt so sorry for you as a kid. [Puts hands over face and cries.] I’m so sorry that happened. It’s hard to see your parent go through it.

We didn’t know any different. I can remember being huddled with my family, with my brothers and sisters. That was all we had. We were huddled and frightened and scared. And my mum did her best and I don’t look back in judgement of any of them.

Every step I take forward, my children take a step forward. And every step they take, their children take

You really don’t. There were times when I thought you were giving some of them an easy ride. I was almost yelling at the book at times: “No, that is not OK!” But you don’t judge them and it’s a beautiful thing.

You have got to remember where they came from, too. When I think about my life, I know stuff that’s not in [the book] that you guys don’t, and my life was almost a dream compared to theirs.

You were talking about how at ease Nanna was at the end of her life. She’d had a rough trot.

I had mixed emotions when she first went into hospital this time. I was thinking, “I’m just starting to get my life together and she’s leaving me again.” I felt this sort of abandonment thing happening with me. But when I went to see her and I held her hand, it was the opposite. It was like the closest she’s been. She was there and she was at peace. She wasn’t angry and she wasn’t going anywhere. That was the difference. It was really pretty moving [cries].

That’s enough. I mean, hopefully your other interviews will be easier than this one. I’m crying and you’re crying. I think that’s enough.

It’s hard going out and talking about the book. To get up and talk about it in public, my throat goes. It’s very difficult. But it’s therapeutic. It’s cathartic.

We’re bearing witness to your life in a way that hasn’t really happened before.

It’s like, should I be doing this? It’s very difficult.

But it’s important.

It’s important for my children. I think the more stuff I deal with now, the better. It’s that thing about being intergenerational. Every step I take forward, my children take a step forward. And every step they take, their children take.

Reading the book, I’ve never felt better about quitting booze. I should have quit sooner! It’s brutal, but those lessons have been passed down.

They’ve been backhanded down. Those lessons have been backhanded down from father to son [laughs].

Jimmy’s live show tours theatres nationally in November and December; jimmybarnes.com

Originally published as The untold story of Jimmy Barnes’ harrowing childhood