‘He’s been gone almost as long as I had him’: Rosie Batty’s heartbreaking reality

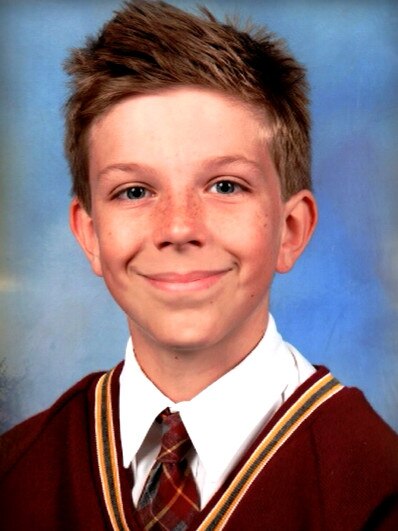

She became a symbol of grief and resilience in the aftermath of her 11-year-old son Luke’s murder at the hands of his father in 2014. Now Rosie Batty is finding hope.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

She became a symbol of both unvarnished grief and untold resilience in the aftermath of her 11-year-old son Luke’s murder at the hands of his father in February 2014.

But while his death forever altered the course of her life, Rosie Batty has also found purpose in her advocacy work – and, as the name of her new memoir suggests, she has also found hope.

As she joins editor-in-chief Sarrah Le Marquand on Stellar’s podcast Something To Talk About, Batty reflects on keeping Luke’s legacy alive 10 years on.

As you and I are speaking today, it’s not been long since the 10-year anniversary of your son Luke’s murder at the hands of his father, on February 12, 2014. Can I start by asking how you felt coming up to that anniversary?

Look, it’s always a time of year that I know is coming – and I perhaps don’t fully recognise how I feel until I’m through to the other side of it. On one level, you can’t believe 10 years have passed. On another level, you can’t believe it ever happened and that you actually were a mum with a wonderful young boy you adored and who was the centre of your world. So you know you’re going to sit heavily with feelings. This 10 years was very significant and I feel it will be next year as well, because Luke was only 11 when he died, and next year I would have lost him for as long as I ever had him. That’s what I wrestle with. Not all of the time, but on these times of the year that are particularly relevant to Luke.

Listen to the full interview with Rosie Batty on Stellar’s podcast, Something To Talk About:

In your upcoming memoir, Hope, you write about how you buy Luke a card on his birthday every year, write him a message and light a candle. Is there something you do on certain days, such as an anniversary or on Christmas morning, as a way to observe the massive void on those occasions? I’m still lighting a candle each day. That flame makes me think of his energy and presence. He has a memorial garden at the Tyabb cricket oval where he was killed, and I go there often with my dogs because it’s a nice walking area. I take yellow flowers [yellow was Luke’s favourite colour] and so do quite a few people from his friendship group in the community; this year, particularly, there were a lot of flowers. It is really his birthday and the anniversary of his death that are most significant to me now. People have often thought of me on Mother’s Day and key times of the year like that; they have never been that special to me. Then sometimes [it’s] when you’re not expecting it, like catching up with one of his friends who are now 21 and 22 years old, young men pushing their limits – one is now a father, some are completing their university education and travelling to Europe – and you’re always holding those thoughts of, wow, look at you. But I should be looking at Luke with you. I should be experiencing the worry of being a mum, because I’m sure you never stop worrying about your children, no matter how old they are. Those are the quiet reflections I don’t share but sit with, looking and knowing that I will never get that type of satisfaction or joy in my life, will never be a grandparent, things like that. It’s saddening, and it hurts. But like all of those ceilings, I also know that I will lift and they will pass and I will return to the elements of my life that give me purpose, meaning, are fulfilling, and bring me contentment and moments of joy.

Hope begins with a beautiful dedication to your son: “Luke, my quirky, fun-loving and sensitive little boy. How I still miss you every single day, and I know that I always will.”

Is it painful to reflect on who he was, who he would be?

Do you still feel that desire to keep his memory alive of what he could and should have been?

I’m not as driven as I was in those early years. I ploughed into my advocacy and campaigning and set up a foundation in his name. I was compelled to do those things; that

was absolutely the right thing for me to do at that time. But at some point, I realised I couldn’t bring him back, that I couldn’t change this outcome, no matter how hard I tried. I had to accept the finality of losing Luke.

People don’t always know what to say, and I do enjoy people sharing a funny story about Luke, a moment in time or some recollection of who he was.

When their parents – or they – share that with me, it makes me feel so pleased that in their own way he will never be forgotten, so I don’t have to publicly look for him to be remembered. I know he is remembered.

That’s credit to the work you’ve done since the morning after his death, when you ignited a national conversation about domestic and family violence when you said to the assembled media: “If anything comes out of this, I want it to be a lesson … Family violence happens to everybody, no matter how nice your house is or how intelligent you are. It happens to anyone and everyone.” A decade on, do you feel that message is now better understood in this country?

I do. And if I had never done anything other than speak that morning, perhaps that moment in time [would have been] the lasting impression that people have. I spoke out and had impact in a very raw, authentic way that took people by surprise, and by that [I mean] they were surprised I was standing up talking, but also that I wasn’t speaking with anger and bitterness and blame – and I think that allowed space for those who needed to reflect about perhaps what they needed to do or could have done differently. I didn’t have a script and an agenda. I’m very pleased and relieved that what I did say seemingly has stayed in people’s minds and had the effect I wouldn’t have dared even imagine.

I’m the ambassador for Women’s Community Shelters, one of the Australian charities in the sector whose work you have supported in the course of your campaigning over this past decade. I asked Annabelle Daniel, the CEO of WCS, if she had a question

I could put to you, and she asked: “What do you see as being Australia’s next frontier in ending domestic and family violence?”

That’s a big question. We all play a part in stopping violence towards women and children, and we’re still struggling to comprehend the link between that and gender inequality. We all look [and tell ourselves] “Other people behave in that way, that doesn’t happen to people like me; what I’m doing or what I’m experiencing isn’t really violence.” I’ve concentrated a lot over the last 10 years [on] trying to shift the victim-blaming narrative towards accountability on the perpetrator [who is] choosing violence. This is generational change. If we’re not looking [at] “How do we prevent it? How do we stop it before it starts?” we’ll always be at the top of the cliff. We’ll always be sorry at the bottom of the cliff, responding to people in crisis who are already suffering in varying ways. We still need to look at our systemic responses. This change is taking so much longer than any of us ever wanted.

Your book is about what happened after the worst day of your life and how you managed to reclaim hope when it was seemingly all lost. At what point during the past decade did you start to think that maybe you could and would feel hope again?

I had moments of that quite early – when I could go out with friends and enjoy a nice dinner and laugh at something, enjoy nice wine, go to the movies. I started to realise that, actually, there are moments I can enjoy and there is laughter … Sometimes it’s black humour but there is still laughter. It helped me realise it was going to get better at some stage. I lost my mum when I was six and it felt like I’d been here before.

Some good friends were going on the coast to coast trek in the UK; this was around three years since Luke had died and I said, “I want to come.” I always had wanted to do the great walks around the world, and my family all live in the UK – that’s where my origins are. And let me tell you, it was tough. I’d [had] weight gain, I’d been drinking every day, and from the moment I lost Luke, I started to smoke again. So I was very unfit and very unhealthy, and

I did need that circuit breaker. I think that was a turning point. There’s nothing more invigorating than walking through the most astounding, beautiful scenery and pushing yourself – safely – through a lot of physical discomfort. That was when I really felt “I can do this and there is more that I want to do.”

I want to go on more walks – in fact, I’m going to go on as many of these walks as I can for the rest of my life. And it gives me a reason, as I’m now 62, to be very mindful that I want to be able to enjoy my latter stages of life. I’m not perfect. I do still like a glass of wine on occasion, but I definitely gave up those cigarettes.

Let’s move forward a few years after that trip to 2020. You had been so busy, and then along came Covid and for you, living in Melbourne, one of the longest lockdowns in the world. In Hope you write about how you started packing some of Luke’s things away, and that “I learnt a lot about myself, and was able to gain a sense of control over my life that I hadn’t had since Luke died. It was frustrating at times, but it gave me time to catch my breath, reassess my life and remind myself what was important.”

Do you think you needed that enforced pause?

Yes, probably. But what I really struggled with is I was totally alone; everybody I knew had turned to what they needed to do and prioritised their relationships, their families, their children, their elderly parents. It was very confronting to realise that as a single woman with no children and no family living here, I was no-one’s priority, and it made me feel very abandoned and isolated. Somebody said to me the other day, “Do you ever really stop grieving?” I think maybe it’s like the layers of an onion, where you don’t even feel there’s more grieving to go. In that real isolation, there was further grieving. There wasn’t this distraction of being able to be social, and work, and do the things I can now see distract you. So without those, I sat in deep grief.

I did go through some of those personal items of Luke’s that I hadn’t got to, like his school books, his kinder stuff, his artwork. That was painful. You see the innocence and where he was at, and [it] made me realise: I never sat down and looked at his school work with him and said, “Oh, that was great; look at that lovely picture.” I just saved them. But when was I ever going to take the time to look at them? Is that what you do on their 21st birthday? You present them with a stack of embarrassing photos? I thought, why did I never take the time to sit with and talk with him about photos in my picture album of his birth? That’s what really saddened me, that I was often just busy. What do we save things for? When is the right time to really look and absorb them and appreciate that journey of childhood as they progress into different stages?

In those dark moments, the only human contact I had a lot of the time were dog-walking colleagues within my 5km radius. Sometimes we were meeting with masks on, but at least we did have some human connection. It made you really understand the importance of human connection and the relationships we have. I was fortunate to be in a position to be that reflective and to be able to sit without great uncertainty and to be able to be privileged enough, I suppose, to make the most of it.

You mentioned the word joy early in our conversation. There were glimmers of hope that, perhaps surprisingly, you managed to find early on. How often do you experience joy in your day-to-day life – conscious, of course, of that analogy of the layers of onion and the grief that’s clearly always there?

I think you need to practise really recognising some of those moments because they’re so easy to just rush through and not focus on. I love walking down one of the local beaches. The dogs … that’s their heaven. They love running in the shallows, looking for fish that they never catch, and seeing that they have such happiness, how can you not feel joy? The last few days, I haven’t felt a lot of joy, but I do try to appreciate and know that will pass. I’m working on something at the moment, with my book, that’s bringing me a lot of satisfaction, a lot of actual joy. There are a lot of people who I don’t always realise how loyal, how important they are and have been on my journey since losing Luke.

The friends I’ve made through my advocacy and the work that I do – you know, I’m part of a tribe of not just women, but people who are passionately spending their lives and their working moments trying to make the world a better place. I’ve had the most amazing 10 years. I’ve travelled extensively. I’ve met extraordinary people. I’ve been to some beautiful places. I’ve had the flexibility and the opportunity because I’ve had some kind of income that was more than when I was a single mum and struggling to keep a roof over our heads. I’ve had so much to be thankful for, and it’s always been a bit bittersweet, because it’s all because of that day I spoke out after Luke died. Life is a journey and it’s a work in progress. I’m still learning, and I’m still curious, and I hope to always be like that.

Hope by Rosie Batty ($35.99, HarperCollins Australia) is out April 3, and is available for pre-order through all major bookstores.

Listen to the full interview with Rosie Batty on Stellar’s podcast, Something To Talk About: