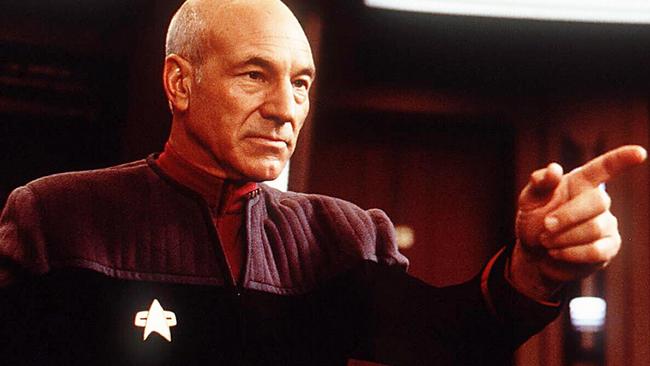

Star Trek great Patrick Stewart on Picard, his abusive childhood and why he’s worried for the future

Ahead of the second season of Star Trek: Picard, Patrick Stewart reveals why he’s ‘distressed and disappointed’ by the world of 2022.

SmartDaily

Don't miss out on the headlines from SmartDaily. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Star Trek great Patrick Stewart admits he is nowhere near as hopeful for the future of the human race now than he was 35 years ago when he first signed on to play Captain Jean-Luc Picard – but he thinks we’ll get there in end.

“I am less optimistic today than I would have been in 1987,” he says.

“I’m less optimistic in the short term – but I’m still as optimistic as I always was in a long term.”

Ever since the original Star Trek first hit screens more than half a century ago – and in two dozen TV and movie spin-offs since – the cult sci-fi phenomenon has painted a mostly rosy and idealistic vision for humanity.

In his show, set about 300 years in our future, original creator Gene Roddenberry envisaged a time when humans had evolved beyond greed, poverty, materialism and environmental degradation to become the United Earth, part of a vast federation of like-minded planets.

Using the exploits of William Shatner’s Captain James T. Kirk and Leonard Nimoy’s pointy-eared Vulcan Mr Spock, Roddenberry and his fellow writers explored hot-button issues of the ‘60s such as racism, sexism and war, as the Starship Enterprise boldly went were no one had gone before, encountering new civilisations on a voyage of exploration and discovery.

Stewart played Picard in the hugely successful The Next Generation – still the most popular of all the Star Trek iterations – for seven seasons on TV and four films.

Ever since he hung-up his phaser after 2002’s underwhelming final TNG film, Star Trek: Nemesis, he’s been fielding offers to return to the signature role, even while his career continued to soar thanks to the hit X-Men superhero franchise, in which he played the wheelchair bound telepath, Professor Charles Xavier.

But Stewart held firm against making “more The Next Generation” and only slipped on the Starfleet uniform once more, when he finally was pitched an idea that interested him.

In the first season of Star Trek: Picard, fans met an older, frailer, more vulnerable version of the character, reflecting that decades had passed in the fictional world, just as they had for Stewart himself.

Not only that, the real world in 2020, when Picard first aired, was far removed from the 1980s and, as star and executive producer, Stewart was adamant that show – and the issues it explored – should also reflect that.

“The whole nature of the relationship of countries, of states, of continents, the relationships of people being denied the freedom to be who they are, and to be treated in the same way in both a social as well as a political sense – all these things have changed,” Stewart says.

“And we have been making references to that much more in Picard than we ever did in TNG. I’m very glad about that. It feels like a very grown-up show. I’m not saying TNG wasn’t – I am so proud and what we did with TNG was extraordinary – but this is something quite different.”

Rather than the utopian, harmonious, environment usually seen in Star Trek, the second season of Picard presents an alternative version of Earth that is run by a ruthless, warmongering, authoritarian regime trying to impose the supremacy of the human race on alien cultures while desperately trying to quell resistance and rebellion caused in part by a dying planet.

Viewers won’t have to squint to hard to find real-world parallels in the series, and the proudly “liberal” Stewart says it saddens him to think that’s a more likely future based on the geopolitical events of recent years.

“I am profoundly disappointed, distressed and fearful of much that I see happening, not just in the Far East or not just in the Middle East, but in our next-door neighbours,” he says.

“There seems to be selfish interest that is beginning to swamp societies everywhere and a carelessness about people who need help.

“And this has come around only in the last few years and it is so disappointing. I don’t think it will hold, I really don’t. I believe that we do have a better future and we shall get through these times. I hope some of that might actually happen while I’m still here.”

Picard also doesn’t shy away from the thorny issues of ageing, mortality and the exploration of what makes a good and valuable life. At 82, Stewart says that these are questions he increasingly asks himself and he’s committed to making the most of whatever years are left to him by using his fame and influence to do some good in the world.

“My associations with organisations has become much more specific than it was and I pay more attention to the work that they do and I involve myself in it as much as I can,” he says. “Which isn’t very much and certainly feels not enough – but I can.”

Stewart has been a long-time supporter of human rights champion Amnesty International, as well as the New York based International Refugee Committee (“the refugee problem is going to be enormous for decades yet to come”) and the UK-based euthanasia campaigning organisation Dignity In Dying.

His other main causes are much closer to home, having grown up in the north of England in the post-WWII years in a violent household.

“There is a wonderful charitable organisation called Refuge in the UK, which is about violence towards women,” he says.

“My mother was beaten by my father, he was a weekend alcoholic and the weekends were challenging for all of us. So Refuge is doing an extraordinary job protecting these women giving them somewhere to go to.”

Through his campaigning for Refuge and openly sharing the personal stories of his experiences with domestic abuse, it was pointed out to him that his violent father almost certainly suffered from untreated post-traumatic stress disorder, from his days as a soldier witnessing Nazi atrocities during WWII.

The revelation made him not only reassess his opinion of his father, but also led to his involvement with Combat Stress, which looks out for the welfare of soldiers past and present who are suffering from PTSD.

“The only treatments that people who were allegedly suffering from shell-shock – that’s what they called it – all they would have been told was to pull yourself together and act like a man,” Stewart says.

“Nothing else, that was it. And I felt bad for my father and I wish there had been help for him because I think he would have embraced it if it had been possible.”

Star Trek: Picard streams on Amazon Prime Video from March 4.