From reducetarians to climatarians, more people are breaking up with meat

Just 10 per cent of us identify as vegan or vegetarian - so what’s behind the drop in meat-eating?

SmartDaily

Don't miss out on the headlines from SmartDaily. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Australians are voracious carnivores, but as concern grows around the health and environmental implications of red meat, more people are choosing to cut back.

While just 10 per cent identify as vegetarian or vegan, recent years have seen a surge in the number of people consciously reducing their meat intake.

One in three Australians now define themselves as flexitarians or meat reducers, according to the Hungry for Plant-Based report - a big call in one of the world’s most steak and BBQ-obsessed nations.

So with World Meat-Free Week ahead, what are the myths, benefits and tips to reducing your meat consumption for better health?

Making the change

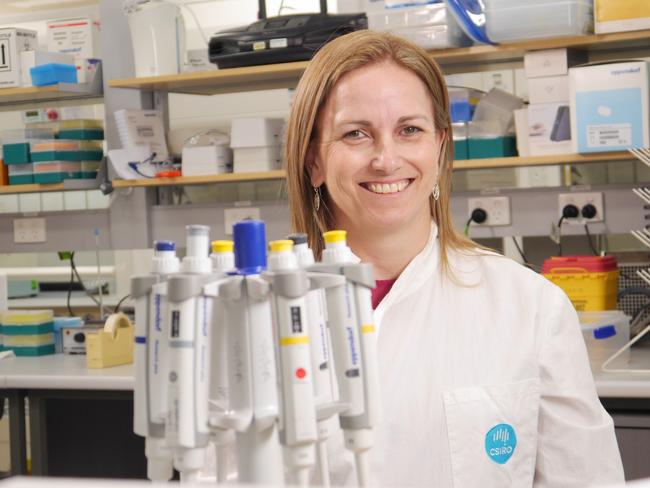

Each Australian chews on 25kg of beef annually, according to Meat & Livestock Australia figures, compared to a global average of under 15kg. Add other red meats, plus poultry and seafood, and the figure rises to 110kg per Australian - around 30 per cent more protein than we need, according to estimates by CSIRO future protein mission lead, professor Michelle Colgrave.

World Meat-Free Week, which kicks off on Monday, suggests people could make a positive impact on the planet by simply switching to one meat-free meal. Meat-Free Mondays and the Reducetarian Movement spruik a similar message, with the latter proposing being vegetarian on weekdays, or vegan before 6pm, as ways to lower meat consumption.

Climatarian is another dietary label gaining traction, referring to dietary changes based on concerns about climate change, from reducing meat and food miles, to avoiding foods grown in heated greenhouses.

Statistics used to support these movements are varied and extensive, from studies that suggest livestock agriculture contributes up to a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, to the industry’s impact on deforestation and heavy water use. A growing mainstream awareness around sustainability and climate change build on long standing animal welfare concerns, and according to People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) spokesman Aleesha Naxakis, add to a compelling argument to go meat-free.

“Vastly more land is required to feed a meat-eater than a vegan, and animal agriculture puts a severe strain on water supplies,” she says. “In addition, the waste and greenhouse gases produced by farmed animals cause serious pollution.”

The impact

With a target to become carbon neutral by 2030, the red meat industry claims it has been unfairly singled out by environmental movements. “It is a fallacy to think that a plant-based diet has no impact on the environment with the use of synthetic fertilisers, chemicals and fossil fuels,” says Red Meat Advisory Council Chair John McKillop. “All participants in the food supply chains are striving to reduce the impact on the environment, none more so than the Australian red meat industry.”

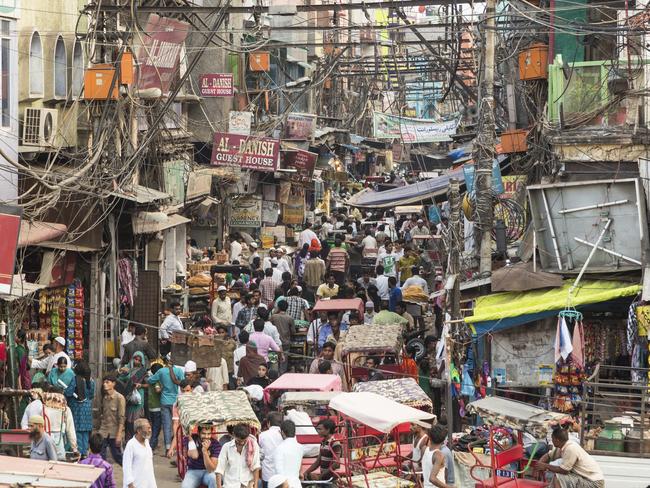

Either way, University of Melbourne professor of sustainable agriculture, Richard Eckard argues that the dietary choices of individuals in the developed world have a limited impact. “I completely agree from a moderation point-of-view, but it’s a very first-world view of the problem to say we should all eat less red meat and save the planet,” he says. “Only 15 per cent of the world’s population earn over $20 USD per day. Such a small percentage of people have a choice over their diet.”

With a rising middle class set to increase demand for animal protein, Professor Eckard says the greatest hope for significant change comes from improved grazing management and methane inhibitors - some with the potential to cut emissions from livestock by up to 80 per cent.

Diversified diet

Focusing on the environmental impact of one food - red meat- is an overly narrow view of the problem, adds CSIRO’s professor Colgrave. “We need to look at the impact of food production systems as a whole,” she says. With an additional 2 billion mouths to feed globally by 2050, and a looming food gap of 70 per cent, Professor Colgrave says embracing a varied diet could be more effective, considering that up to 75 per cent of food comes from just 12 plants and 5 animals.

Fancy a cicada on the barbie? Supplementary proteins, such as insects and algae, are among those being researched by the CSIRO as potential future foods. “A more biodiverse diet will certainly bring nutritional benefits, and with it, an opportunity to lessen the overall impact of our diets on the planet,” Professor Colgrave says. “Australians (need) to be adventurous and try new things – whether it is a centre-of-plate option made from culture fungi, or an algae-fortified pasta.”

Health

The environmental impact of reducing meat consumption may be debatable, but the health benefits are clear. The World Cancer Research Fund recommends eating no more than 500g of red meat per week, which includes beef, pork and lamb, and little, if any, processed meats. This is supported by World Health Organisation classifications, which label processed meats as Group 1 carcinogens (known to cause cancer), and red meat as Group 2A carcinogens, meaning it probably causes cancer.

“Red meat does not cause bowel cancer on its own, it’s just that we consume too much of it,” says Associate Professor Teresa Mitchell-Paterson, bowel care nutritionist for Bowel cancer Australia, noting that only five per cent of Australians meet the recommended intake of fruit and vegetables.

A predominantly plant-based diet enables a lower intake of saturated fats, she adds, combined with a higher intake of antioxidants, plant chemicals, fibre, water and fluid: “These benefits we know can help to reduce incidence of things like cardiovascular disease and diabetes, to name a few.”

Chef Teresa Cutter, founder of The Healthy Chef, says embracing plant-based eating doesn’t mean you have to become vegan. Making the change can start with meals based on soups and salads, and small changes to the recipes you already cook. “A spaghetti Bolognese can be transformed by a mirepoix of vegetables,” she says. “For plant protein I love adding grated tempeh, which resembles mince.”

Mitchell-Paterson suggests starting with two meat-free nights per week. Another option is to reduce the quantity of meat in recipes, and supplement it with another protein, such as legumes. “Beans are a resistant starch - they lessen the contact of red meat against the bowel wall, and the fibre is beneficial,” she says.

“Even if it’s just sometimes, trying to go meat-free can get you used to the fact that meals can be very nutritious, and very delicious, without a chunk of meat.”