Queensland researchers in new depression battle

A groundbreaking treatment using a new form of brain stimulation will begin government-funded clinical trials next year. ALL THE DETAILS

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A groundbreaking depression treatment co-pioneered by Queensland researchers using a new form of brain stimulation will begin government-funded clinical trials next year.

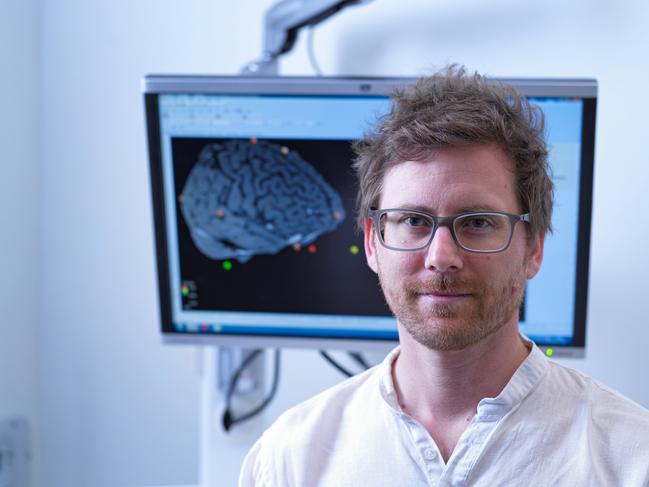

In what is described as an Australian-first and also believed to be a one-of-a-kind in the Southern Hemisphere, robotic analysis and targeted brain stimulation helps to change how active parts of the patient’s brain are and how they communicate with each other.

QIMR Berghofer’s Associate Professor Luca Cocchi and Dr Phillip Mosley have seen “complete recoveries” in patients through transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment at their not-for-profit private clinic – Queensland Neurostimulation Centre.

In conjunction with research and expertise from University of Melbourne’s Professor Andrew Zalesky and Dr Robin Cash, the Brisbane experts have secured National Health and Medical Research Council funding for official clinical trials in 2025.

“Deep brain stimulation has been trialled for depression in the US and Europe, but there have been mixed results. But I’ve been brewing this idea for a long time that all depression is not the same,” QIMR lead researcher and neuropsychiatrist Dr Phillip Mosley said.

“This is a way of treating the brain with various forms of energy to change how active the brain regions are and how they talk to other brain regions.

“What we try to do is identify brain regions that are characteristically disturbed in depression and we change their activity by using a strongly targeted magnetic field.”

Assoc Prof Cocchi said the new treatment was the result of decades of research by him and his colleagues, and others before them.

“We have worked with University of Melbourne researchers to use imaging to map individual brain networks that link to the severity of symptoms of depression, and help us to develop a personalised approach so we can work out where we need to target,” he explained.

“Then we use this robotic set up and we are the only ones in the Southern Hemisphere to do this, to precisely guide the robot to that part of the brain.”

Assoc Prof Cocchi said continued awareness campaigns and media attention on mental health issues had helped to reduce stigma.

“I think this is a very exciting time,” he said.

“Around 50 per cent of people with depression may not respond well to existing therapies, but now with this neuromodulation approach and other approaches that are emerging, there is a lot more hope for people with these mental disorders to get better.”

The QIMR Berghofer team are particularly hopeful that their research can help those with a severe form of depression known as melancholia – which presents similar to Parkinson’s with patients having very slow movement, poor posture, and often struggling to leave their home.

Melancholic depression patients are less likely to respond to psychological treatments and often need very high doses of medication or brain stimulation.

In a separate study, Dr Mosley and his team used Artificial Intelligence to analyse the facial expressions of 70 participants with depression as they watched a funny movie.

The findings showed clear differences between people with melancholia, and people with non-melancholic depression.

In addition to the depression clinical trial next year, Dr Mosley has also secured grants for groundbreaking deep brain stimulation for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, as well as a transcranial ultrasound trial for OCD treatment.

Originally published as Queensland researchers in new depression battle