What Australia can learn from Finland’s laid-back school system

THEY only attend school for four to six hours a day and can use mobile phones in class. Students in this high-achieving country are showing the world how it’s done.

School Life

Don't miss out on the headlines from School Life. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THREE small boys are sprawled on the floor under the stairs, noisily debating the book they’re reading.

Their deputy principal folds his tall frame under the stairs to join them on the floor and chat.

Outside the door, a group of older boys and girls are standing in the snow, logging onto the school’s free Wi-Fi to scroll through their phones.

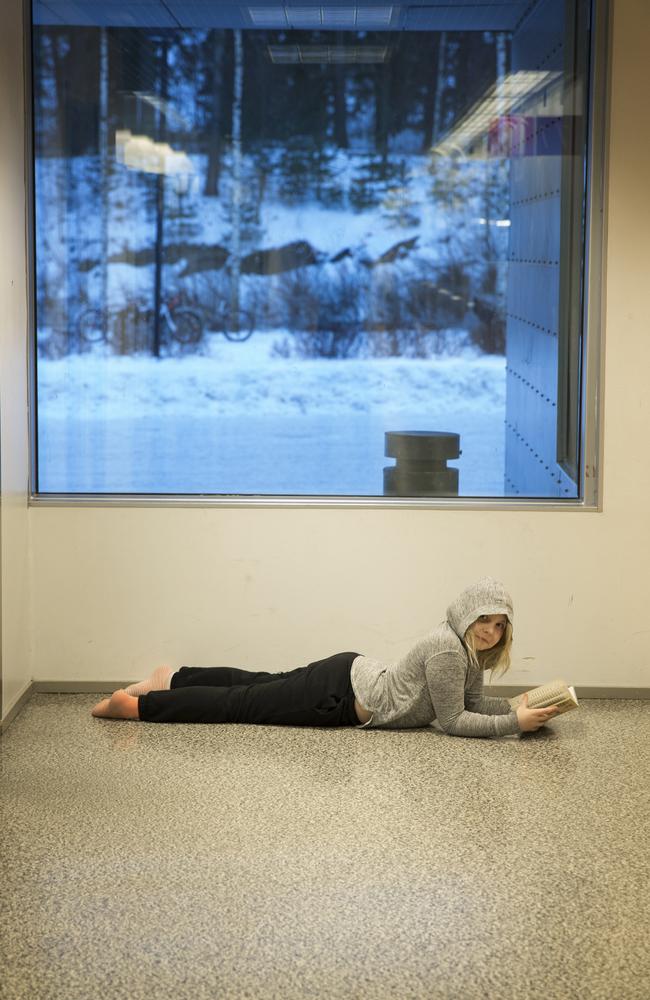

Down the hallway, a small girl is laying facedown on the wooden floor, absorbed in another book, oblivious to the noise around her.

It might not look like it, but all these students are studying. This is how it’s done in Finland, the country which boasts world-leading literacy rates, and has just been named the world’s most literate nation.

Hiidenkiven Pereskoulu is a comprehensive school in suburban Helsinki, the Finnish capital, and has 750 students ranging across the school years one to nine.

The bright, airy school has no fences, no sirens or bells, glass walls in all the classrooms, and open spaces fitted out with picnic tables all over the school where the students, big and small, are encouraged to work together.

Ilppo Kivivuori has been deputy principal for six years, and said the school aimed to give the students flexibility.

Reading is at the core of the curriculum across Finland, which has recently been named the world’s most literate nation, and is consistently in the top group of countries in the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) in maths, science and reading.

“If you take the international results, like PISA, Finnish children have less hours at school, some homework but not much, and they’re not tested at a national level,’’ Mr Kivivuori said.

“It is also the school structure that promotes independence, creativity and responsibility.’’

Formal schooling in Finland starts in the first grade, when students are seven years old. Any tuition prior to that is play-based day care and not part of the schooling system.

Apart from some basics, most students learn to read when they start school — which in the early years runs for only four hours a day. At Hiidenkiven school, that means 8.15am to 12.15pm, although the days become longer as the students progress, with ninth-graders doing a six-hour day.

There are no school uniforms and no shoes inside, and teachers are called by their first names.

Homework is kept to a minimum.

They have subsidised day care in the afternoon for some children, although most go home, and lunch for the students starts at 11am. The students all receive a free school lunch — a buffet of salad, vegetables and stews, and no-one comes to school with a lunch box.

They eat with their teachers, and snacks, lollies and soft-drinks are banned. Water and milk is offered at lunch and the students help themselves.

The lessons are 90 minutes long, and in the middle of the first class, all the young students are required to play outside, where teachers join them in vigorous games of chasey and soccer.

The laid-back approach contrasts with many schools in Australia, where children start formal learning as young as the age of four, and often find themselves weighed down by hours of homework in their later years at school.

Mr Kivivuori said books and reading had a “very important role to play’’ in setting children up for a good education.

“It doesn’t happen in every family but parents are encouraged to read to their kids,’’ he said.

“I read a huge amount to my children including the entire Roald Dahl collection.’’

For years, Finland has been in the top few countries ranked by their PISA results, which are compiled by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and determined by testing around 540,000 15-year- old students from around the world on their reading, science, maths, and problem-solving skills.

In December, Finland rated fourth for reading, while Australia came in 15th.

And last year a broader study, which took in the PISA results, and other factors such as the number of libraries and newspaper titles in each country, ranked Finland the world’s most literate nation.

Australia scored 16th place in that study.

The oldest and most famous bookshop in Helsinki is the Academic Bookshop, first opened in 1893, and now occupying a prime site in a striking building designed by renowned architect Alvar Aalto.

Department manager Petra Kakko said books remained very much a part of Finnish culture.

“Books are alive, very much so,’’ she said.

But sales have fallen in recent years, and the famous old shop, bought by big Swedish publishers Bonnier in recent years, has expanded its offerings to keep people coming in the door, with a Starbucks cafe in one corner, a morning TV show studio in another corner, and the introduction of a toy range, featuring the Moomin characters created by the internationally-recognised Finnish author Tove Janssen.

The shop also sells between 20 and 30 different newspaper titles and has more than 500 magazine titles in stock, as well as tens of thousands of books.

Ms Kakko said most Finnish children would receive a book for Christmas, and were active users of their school libraries.

Dystopian novels such as the Hunger Games were big sellers for children and young adults, while the Harry Potter series by British author JK Rowling, which turbo-charged the fantasy genre, continued to do well.

As well, the Finnish Government funded a major literacy prize each year for the best novel, non-fiction and children’s books, which also sold thousands of copies, if the judges chose more mainstream manuscripts as the winners, according to Ms Kakko.

“The more commercial the better for us,’’ she said.

With the rise of mobile tablets and smartphones, Finland, like most other countries, has seen a drop in reading levels, particularly among boys, and is working to address it.

Ms Kakko said there had been concern for two or three years that children were turning away from books, so a national campaign was held in 2016 to inspire children and teens to pick up a book.

“This was done by organising various reading campaigns and writing competitions. Authors did tours to schools to promote reading,’’ she said.

“This year our country turns 100 and reading is still very much (on the) agenda with lots of different activities and happenings throughout the year.

“Personally, I’d like to see the same thing happening in Finland as in the UK, children spending their pocket money on books. This would require publishers to publish more paperbacks, so that reading would be more affordable. Books have become a luxury item and reading has suffered because of it.

“Luckily our libraries are great and people use them, so all is not lost.’’

Ilppo Kivivuori agrees boys are reading less than girls. He says one of the keys to keeping students reading is making sure they have access to the books that interest them, and the school library, which stacks the classics, is also full of books by Dan Brown, Stephen King, George R.R. Martin and J.R. R Tolkien, as well as Finnish contemporary authors such as Timo Parvela.

The students at Hiidenkiven all study in mixed groups of four, and the school tables and chairs are grouped in floor, instead of desks in lines which face the front of the room.

In the first-grade classroom, teacher Tiina Aalto oversees her young charges as the lights are dimmed and they take turns standing in front of the class, reading aloud as if performing in a play.

“We are doing this three or four times a week,’’ she said.

The second-graders join the younger students at 9am to help, while those who haven’t yet mastered reading basics get extra help from the teachers and support workers, using an app designed by a local university to encourage the students to connect signs with letters, and eventually words.

All learning is phonic, helped along by the fact the Finnish language essentially has the same sounds for each letter, unlike English, which can have multiple sounds for letters and combination of letters.

Ms Aalto said students were taught to respect books and treat them with care, and to absorb and discuss the stories.

“We also allow them to discuss other things so there is a bit of noise,’’ she said of the free reading session.

Pyry, 14, is one of a handful of students studying a diploma in books in addition to his eighth-grade studies.

He is fluent in English — he taught himself watching YouTube videos and listening to his British and Australian relatives, as well as studying it at school — and he reads mainly in English, because the books he likes are easier to get in English then in Finnish language.

“I read fantasy, it’s my only genre,’’ he said

“My last 10 novels I read were in English.’’

Lotta, 15, started reading at school in the first grade and now loves to read fantasy, science-fiction and “realistic novels that tell normal life.’’

“I have lots of books at home,’’ she said.

Keeping up with modern literature and the real world is important at Hiidenkiven. Here, older students do not copy copious notes from the blackboard. Instead, they photograph them on their mobile phones.

They are allowed to use phones in the classroom, and use the school’s Wi-Fi.

Some are even allowed to study while listening to music through their headphones.

While Finland has a national curriculum, it is used more as a guiding principle. The City Board of Education formulates a curriculum for the schools in its municipality, and the individual schools finalise it, based on feedback from teachers, parents and students.

Nationally, cursive writing ceased being taught at the start of the school year in August, and the time has instead been set aside for students to learn computer typing skills.

The Finnish language subject which all students are required to study includes learning about books, and literature history.

“Reading and understanding fiction develops your thinking, creativity and emotional development. It is very important,’’ Mr Kivivuori says.

“We try to move away from exams, although they do them more in the upper grades.’’ Graduation exams are held in high school. These exams determine a university or vocational entry standard, and are used for the PISA results.

Finnish language teacher and librarian Mari Heikkila said students were encouraged to read everything from poems to non-fiction and biographies, thrillers and detective stories.

“I have a boy in the 9th grade reading (influential Irish author) James Joyce and (Italian poet) Dante, but that is rare,’’ she said.

“We try to give them books for all levels. In the past everyone had to read the same book. As a teacher is it my responsibility to find a book for everyone.’’