Neil Mitchell on 30 years at 3AW and how the pandemic has changed Melbourne

It’s taken 30 years on air for Neil Mitchell to find the biggest story of his career: “I’ve never seen anything that absorbs and engages the public like this.” Mitchell opens up on working from home, why Daniel Andrews won’t come on his show and how Victorians have been let down by their leaders.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Neil Mitchell was doing an “iso clean-up” of his home office when he found a letter from former Premier Steve Bracks.

Mitchell remembers Bracks, in power, as decent and honest. Yet they scrapped and wrestled each week, on-air, much like every state leader has since Mitchell assumed 3AW’s morning slot three decades ago.

Former premier Jeff Kennett used to be a weekly guest. Part imp, part drill sergeant, he once threw a glass of water on Mitchell. When Mitchell for a time wore a blood pressure monitor, Kennett delighted in making it beep.

Kennett’s cabinet ministers would religiously tune in to Mitchell at 9am each Thursday. Not to hear Kennett tease, hector and berate Mitchell, but to discover what their policies were.

Bracks, Kennett’s replacement, was straighter. He looked embarrassed when he dodged the truth. On Mitchell’s 20th anniversary at 3AW, Bracks wrote him a handwritten note: “We are lucky in Victoria to have a real journalist leading the morning news.”

Finding the note, recently, got Mitchell wondering. He has always doubted politicians and their motives. “Whackers,” he calls them.

Bracks didn’t welcome unhelpful questions, but he always showed up for the contest. It made political sense: Mitchell has won almost every ratings period in a reign that matches Alan Jones in Sydney, who retired in May.

That’s what leaders do; they stand to be accounted. Yet some politicians won’t appear on Mitchell’s show any more.

Mitchell has at various times been black-listed by Bill Shorten, Scott Morrison and Julie Bishop, who applied her “death stare” — twice — during Mitchell’s “gotcha” interview about superannuation in 2016.

About three-and-a-half years ago, Mitchell queried Premier Dan Andrews on-air about the consultation process for “sky rail” projects.

“You could see his face turn,” Mitchell says. “I thought ‘oh-oh’, and he hasn’t been back since.”

The “great failing” of the pandemic response, he says, has been the politicians. They don’t trust the people enough to be honest about their mistakes.

He welcomed the Prime Minister’s apology for aged care tragedies, and wishes the local leadership would offer similar candour, if only so the community could “move on”.

Mitchell describes their intolerance to any analysis of their intended spin. They “get cross”, like Shane Warne, when the spin is picked, “then try to hit you out of the park”.

“They don’t want questioning, they don’t believe in the right to question any more, if you don’t cop the spin then you’re an enemy,” he says.

“Why doesn’t Daniel Andrews talk to me? Because he doesn’t want to answer the questions.”

Mitchell, as usual, sounds cranky. It’s his default setting after 30 years of “jet lag”.

A worrier of nature, he dreads the uncertainty of the weeks and months ahead.

He’s also miffed. Saturdays, his one day off a week, have been ruined by the daily government pandemic press conference.

One day last week, Mitchell watched Andrews bat away suggestions that old people were being rejected by major hospitals, to instead be sent back to aged care, to be sedated and possibly die.

“That’s not my advice,” Andrews said, as Mitchell, clutching a nursing care email that told otherwise, swore and yelled at the screen.

The blotted truth frustrates him. Andrews speaks of health department efforts to contact positive people within 24 hours. Yet day after day, dozens of Mitchell’s callers describe delays that undermine the tracing rhetoric.

A caller on that morning’s show was isolated for five weeks after receiving a positive test, then a negative test, then a positive, then a negative. Then, she was told she never had the virus.

Unlike most political disasters, the Victorian pandemic has cost lives as well as money. The state’s bureaucracy has been exposed. Vulnerable people have died for its shortcomings. Andrews’ performance that day, according to Mitchell, was an “absolute disgrace”.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” Mitchell says of the pandemic.

“I lived through the Whitlam dismissal, I lived through the West Gate Bridge collapse, I lived through Black Saturday, 9-11, Bali, huge finance stories like the collapse of Ansett, massive unemployment, high interest rates, through how many PMs I don’t know.

“I’ve never seen anything that absorbs and engages the public like this.”

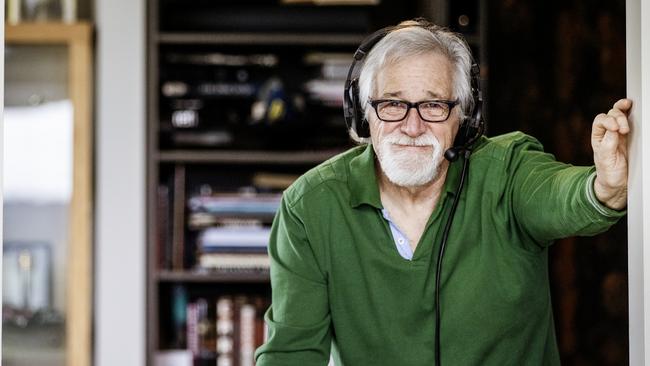

Mitchell has been broadcasting from home since the first lockdown. His office is next to his bedroom, a kind of trap that interferes with his already odd sleeping hours.

Whenever he goes to or from bed, he diverts to the little room with the miniature models of cars and a tractor, as well as a headset to the world.

“I’d really like to be able to close the office door on Friday afternoon and not open it again until Saturday night or Sunday,” he says.

“But I can’t. If I get up at midnight to go to the loo or something I’ll likely go in and check something.”

He’s up at 4am each day, driven in part by his fear of failure. A workaholic, Mitchell applies obsessive care, even if he once rejected a 3AW demand that he take acting lessons to remedy his “monotone” voice.

He worries about the program minute-by-minute. Catch Mitchell at 12.05pm on any weekday, moments after he has finished the show, and he is usually ticking himself off for the times on-air that morning when he had been too abrasive or too soft.

“The other day, I think the beginning of stage four, through the three-and-a-half hours of the program we received three emails a minute, for every minute,” he says.

“The phone lines, we’ve got nine, were full before I got on-air, and the moment one would drop out, it would fill again. They are desperate to talk about it, they’re desperate for connection, they’re desperate for information.

“There’s quite a bit of anger and a little bit of fear. Sometimes I get off air and feel like I’ve been counselling up to half a million people for three-and-a-half hours, and that’s dangerous. It’s unprecedented.”

He’s hardly complaining; he has a job, a nice place to live, and the self-imposed burden of communicating, analysing and bringing together the people of Melbourne during the biggest issue of his career.

It follows that he is crankier than ever. Mitchell is the voice of Melbourne in its bleakest time. He has never been busier. For close observers, his level of grumpiness serves as a rough measure of his satisfaction.

He’s 68, an age when blokes generally compare golf rounds, ailments and grandchildren. Off the booze for a year, he intends to indulge a white wine over dinner in the months ahead.

Virus or not, Mitchell doesn’t go out much. He describes himself as “shy” and “private”.

One of the best connected people in Melbourne, Mitchell doesn’t have many close friends. He is grieving the recent loss of two of his closest mates — Les Carlyon and Tony Beddison — one after the other, who had guided and counselled him since last century.

They both steered Mitchell when he was “being an idiot”. They got him (one called him “the Methodist”). He “desperately misses” them, he says, as if describing the loss of parents.

He checks in with the families of these departed friends, sometimes with a chocolate cake at the front door.

On hearing of a friend’s medical malady, he conjures an instant appointment with the best specialist. He chases up radio subjects, years on, to check how they are going.

There’s a thoughtfulness, an integrity of being, which defies an industry laden with performers and narcissists. His endurance rests on stability and constancy, as well as his ability to break stories.

Former boss and colleague Steve Price points out that many broadcasters rely on bombast to get noticed. Mitchell, conversely, wins his audience by being a campaigner and an “ombudsman”.

“Ross Stevenson is the bloke you want to go to lunch with,” says a close friend, of Mitchell’s breakfast show colleague.

“Neil is the bloke you want to be the executor of your will. You know he’d do the right thing if you weren’t there.”

The Real Neil is an observer, not a player. Endorsements and advertisers are an accepted by-products of his trade, but he doesn’t do ads. For him, it’s the price of credibility.

He hasn’t bent much to the changing technologies and shifting fashions of thinking. His quirks are timeless: the love of his perch and the lack of vanity; a fear of being poor rather than a desire to be wealthy.

In 1999, this journalist wrote a piece about him. “I don’t think I’d like to work for me,” he said then.

Then, as now, he sat at the microphone every morning to have “a piece of you taken away and chewed up”. Or, as a friend puts it, to jump into the “boxing ring” day after day.

His care for the audience is undimmed. His listeners surprise, amuse and annoy him. If there is a world-weariness to Mitchell, he also leaps on acts of kindness.

Helping ordinary people is his biggest reward, often away from the microphone. A string of causes — from dying children, mothers and cancer sufferers — has brought him to tears on-air.

He is more relaxed, more confident than the middle-aged Mitchell. That conflicted blend of private and public of his off-air and on-air personas has merged.

He’s the bloke who stands in a corner at a function, yet he’s also the first called upon for a eulogy or speech. He’s a broadcaster who cannot stand the sound of his own voice.

He’s never had a longer than three-year contract, by choice, and it’s up for renewal by the end of this year. He wants to see out the pandemic, feels obliged to. He doesn’t know if he will feel energised when it passes, or emptied.

The father of two grown up kids, and husband to Selina, Mitchell has never had hobbies. Work has been a singular pursuit.

He boasts a green-and-yellow John Deere tractor at his beach house. Driving it relaxes him, as does reading, cooking, walking, meditation, playing with the dog and mowing the lawn.

Yet these sound like distractions from work, not pursuits of passion. Retirement, and the idea of sitting at his holiday home staring at the sea, frightens him.

“I’ve got no idea where it will all go but at this stage I want to keep going,” he says. “You couldn’t walk away from this. It sounds stupid but I feel a sense of responsibility to the audience that I wouldn’t walk away — unless they sack me.”

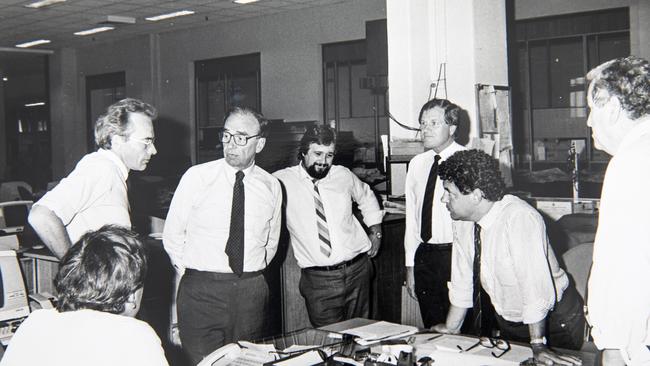

He doesn’t regret his occupational single-mindedness, which traces to his start at The Age newspaper when he was 17. A colleague recalls that he looked like a “chubby kind of Christ” — long hair, bad clothes.

He seemed fully formed at a young age, quiet and productive, but poised of a manner that most public figures do not attain until middle-age. He learned to get stories, and drink beer, at the John Curtin bar in Carlton, where Bob Hawke could normally be found.

Mitchell sounded like a “teacher”, the colleague says, nodding to Mitchell’s father, Jack, who moved his family around Victoria in teaching promotions. Mitchell was 17 years younger than his oldest sibling, Ross, and grew up as a kind of single child to older parents.

His father died of a stroke when Mitchell was 19, soon after retiring. Mitchell acknowledges – if not accepts – that his drive may stem from seeking his absent father’s approval.

His thrusting sense of right and wrong is generational: Ross, a real estate agent, never doubted that his kid brother would go after him if he ever committed improper practices.

Mother Edith liked that Mitchell worked in newspapers — he was editor of The Herald from 1985 but quit in 1987 and filled in for Derryn Hinch on the Drive program on 3AW — but shied from radio callers who abused her boy. Until her death, she described his radio work as not “a real job”. Mitchell himself admits he once felt the same. As a newspaper executive he had treated talkback callers as “unimportant people”.

Mitchell’s favourite on-air moments involve sadness and ordinary people. The Christmas party he arranged in a November for seven-year-old, Mikayla Francis, who had weeks to live. The legislative change after Clare Oliver, dying of melanoma, went on-air to talk about the evils of solariums.

He successfully lobbied Health Minister Greg Hunt to subsidise lifesaving cancer treatment in the US for a Mildura woman, Gina De Angelis Argiro.

These are the moments when he has “achieved something”.

Mitchell is haunted by the night of Black Saturday in 2009.

“There were people ringing from Kinglake in sheer terror, ‘what can you do’, ‘can you get somebody to us’, ‘can you help us’,” he says.

“I don’t know to this day whether some of them are alive or dead. You could sense the desperation in their voices, and you’re sitting there in a safe studio, powerless to do anything.”

As Alan Jones has pointed out, he wouldn’t succeed in Melbourne, and Mitchell would not succeed in Sydney. They’re different audiences; Sydney shock jock Ray Hadley once told Mitchell on-air to stick his head up his bum.

Mitchell sighs at the mention of chronic feuding between himself and Eddie McGuire. How ho-hum, he seems to suggest.

Mitchell doesn’t dislike McGuire. “But I don’t like his conflicts of interest and I’ve explained why and he doesn’t like me talking about it,” Mitchell says. “He likes to call me a geriatric windbag. He needs a new insult.”

He doesn’t detest all politicians, either, naming Joe Hockey, John Howard and Anthony Albanese among his favourites.

But he does hope the pandemic will bring political change. Hackneyed political abstractions, such as “systems” and “outcomes”, shrivel alongside images of the evacuated, malnourished and dehydrated.

Mitchell, a cynic and an idealist, wonders if, post-pandemic, our reduced tolerance for political spin might compel politicians to be more genuine.

“Righto, you bastards, talk to us like we’re real people, none of this bullshit, none of the spin, “ he says. “Maybe some leader will come along somewhere and embrace that.”

If they do, they will probably appear on Mitchell’s show.

“You can’t do it if you don’t love it,” Price says. “Neil’s Melbourne-ness is his strength. He would really be lost if he didn’t get up and do the show every day.”