Controversial ‘three-parent IVF’ technology could soon be available to Australians

A new IVF program in Australia could save the lives of babies who inherit life-threatening genetic conditions. So why is the plan so controversial?

Health

Don't miss out on the headlines from Health. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Controversial ‘three-parent IVF’ may soon be allowed in Australia under a proposed law change aimed at preventing parents passing on horror genetic conditions to their children.

However, a host of scientific, ethical and social dilemmas are now being evaluated to determine the wider implications of combining genes from two women and altering the nation’s cloning laws.

The Australian Government has called on the National Health and Medical Research Council to weigh up the scientific and moral considerations of mitochondrial donation – where DNA from the eggs of two women are combined to remove malfunctioning genes.

If allowed, it is estimated mitochondrial donation would be used in about 60 births a year to prevent diseases that typically see children die between the ages of three and 12.

An expert committee has produced a discussion paper to outline the issue, however NHMRC chief executive officer Professor Anne Kelso said it was now up to ordinary Australians to decide how far they are prepared to allow genetic manipulation of embryos.

“For some people the most important thing will be that we can offer hope to families who have mitochondrial diseases because it can be very severe and shorten people’s lives dramatically,” Prof Kelso said.

“This technology offers the possibility of families having healthy children that are still genetically related to both the parents.

“There are clear benefits if it works, but we’ don’t yet know how safe the technology is because there is so little information from around the world.

“For some other people the technology will present moral challenges.”

While mitochondrial donation is widely known as ‘three-parent IVF’, only a minuscule amount of DNA from the donor would actually be passed on to a child.

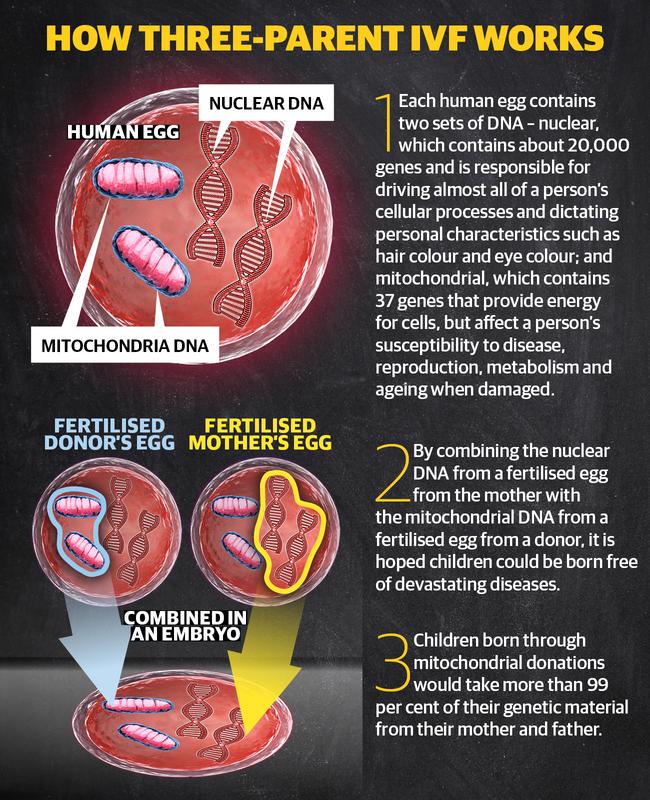

A human egg contains two sets of DNA;

NUCLEAR DNA, which contains about 20,000 genes and is responsible driving almost all a person’s cellular processes and dictating personal characteristics such as hair colour and eye colou;

AND mitochondrial DNA, which contains 37 genes that provide energy for cells, but which impact a person's susceptible to disease, reproduction, metabolism and ageing when damaged.

To avoid passing on a woman’s damaged genes to her child, the healthy nuclear DNA of one of her eggs can be removed and inserted into the healthy egg of a donor which has its nuclear DNA removed.

After the UK legalised the practice, the Australian Senate last year recommended changing the cloning act and the embryo research act to allow the procedure.

Rather than rule on the highly contentious issue, the Government has asked the NHMRC to undertake expert and community consultations, including a public forum in Melbourne on November 18.

Murdoch Children’s Research Institute geneticist Professor David Thorburn said concerns remain over the effectiveness and risks of the procedure, however he is in favour of it under the strictest circumstances.

“Mitochondrial disease is actually 300 different diseases, so there’s actually quite a bit of variability but many of the children die in the first days or weeks or months of life and at the moment we have no effective treatment,” Prof Thornburn said.

“I am supportive of this, provided it is done in a similar way to the UK where it is in cautious, regulated process where families who might want to use it are aware of the potential risks and limitations.”

University of Adelaide medical law and bioethics researcher Associate Professor Bernadette Richards said any change would need the tightest of restrictions, including the requirement of licenses for patients and practitioners.

“There are very specific concerns that people have, that this is opening the door for full-blown genetic modification … so if a law was crafted it would have to be incredibly careful and it would have to be incredibly clear,” Assoc Prof Richards said.

“We are not curing mitochondrial disease, we are not saving people, none of these children who are now living could have actually been born – a different child would have been born.

“We are looking at the future of humanity and these are important questions. This is something we all own, not just a group of politicians.

“We all should own our future and what we are prepared to accept and what we are not prepared to accept.”

MORE NEWS:

THE HORROR FIND IN WOMAN’S STOMACH

DIY TEST COULD DETECT CERVICAL CANCER

SIMPLE BLOOD TEST COULD STOP BREAST CANCER

Another member of the expert committee, Catholic Theological College ethicist Reverend Kevin McGovern, said he was “uncomfortable” with the prospect of mitochondrial donations because traditional egg donations were a more simple and certain way for families to have children free of genetic risks.

“This is a dilemma with no simple best way forward,” Rev McGovern said.

“The primary benefit is for the mother who has a child which is genetically her own: the primary risk is to the child, who runs a risk of still being effected by mitochondrial disease.”

THE UNKNOWN BEHIND MITOCHONDRIAL DISEASE

Nobody knows how long Maeve Hood will have with her family.

But her parents Joel and Sarah Hood are determined the beautiful three-year-old should be the last in their family line to suffer from the devastating condition hidden in her genes.

Diagnosed with Leigh’s Syndrome – a form of mitochondrial disease that has a life expectancy of between three and eight years – the McLoed girl has so far surpassed most expectations.

“We are being told to prepare, that she might regress,” Mr Hood said.

“She is an amazing individual. But that fact her time is limited, every day we look at her and know that, unfortunately, it could be her last because it does go very quickly for kids with her condition.

“The hardest part is knowing we are going to have to explain to her sisters that once she starts deteriorating she is most likely not going to live to see double figures.”

For her first six months Maeve developed like all babies until she was struck down by a virus and spent four days in intensive care.

Worse, the virus triggered a the neurological condition which had previously been dormant in her DNA. Over the next six months Maeve stopped growing, became weak, sick and could not swallow.

As Maeve’s motor skills reversed it took a year before scans showed clouding on her brain and she was diagnosed with Leigh Syndrome.

Tests are now continuing to see is Ms Hood and their other daughters Isla, 8, and Olive, 6, also carry the mitochondrial malfunction.

As they push to make the most of every day with Maeve, the parents are all-too aware the disease can also be triggered later in life.

“It is wiping out whole families and that is the hardest thing for us, knowing (our) other kids are potentially effected,” Ms Hood said.

“Hopefully the girls don’t go down with it and they can get to live a normal life.

“If we get to the point of them having children, we’d really like to be able to completely wipe it out of the family and Maeve, unfortunately, was the only one put in the situation where she didn’t get to live that normal life.”

The family has met with Health Minister Greg Hunt to discuss the case for allowing mitochondrial donations in the hope the next generation of their family will be free from such fears.

“There is an opportunity there to try and fix this problem with all the research we have done, it would just be nice to see it happen sooner,” Mr Hood said.

To make a submission to the NHMRC’s mitochondrial donation consultation or gain more information about public forums visit www.nhmrc.gov.au