Alzheimer’s breakthrough a new hope for dementia sufferers

Dementia experts have cautiously welcomed a shock breakthrough in the trial of a new drug, giving hope to early-stage Alzheimer’s patients.

Health

Don't miss out on the headlines from Health. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A new drug that slows cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s patients by 27 per cent has brought new hope to suffers of dementia, according to a new trial.

Experts cautiously welcomed the results while warning the benefits were comparatively small compared to the serious side effects of the new drug, lacanemab.

Data published in the New England Journal of Medicine found the drug slowed cognitive decline over the 18-month period of the trial

The results were broadly welcomed by researchers and campaigners for patients with the disease, including Bart De Strooper, director of the UK Dementia Research Institute.

“This is the first drug that provides a real treatment option for people with Alzheimer’s,” he said.

“While the clinical benefits appear somewhat limited, it can be expected that they will become more apparent if the drug is administered over a longer time period.”

But trial data also raised concerns about the incidence of “adverse effects” including brain bleeds and swelling.

The results showed 17.3 per cent of patients administered the drug experienced brain bleeds, compared with nine per cent of those receiving a placebo.

And 12.6 per cent of those taking the drug experienced brain swelling, compared with just 1.7 per cent of those in the placebo group.

Deaths were reported at approximately the same rate in both arms of the trial of the drug, which was developed by firms Biogen and Eisai.

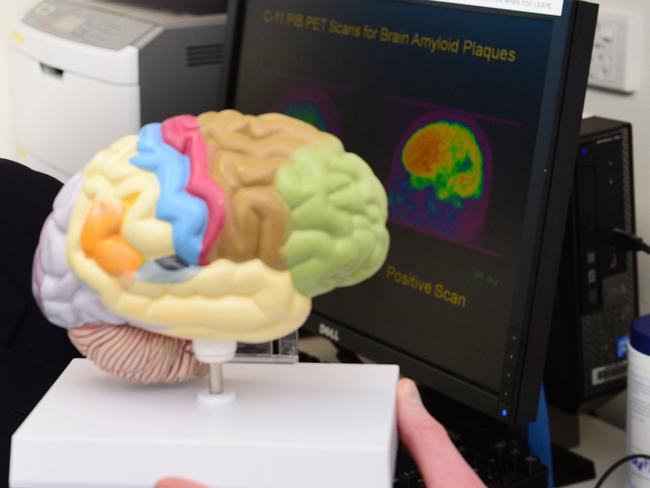

In Alzheimer’s disease, two key proteins, tau and amyloid beta, build up into tangles and plaques, known together as aggregates, which cause brain cells to die and lead to brain shrinkage.

Lecanemab works by targeting amyloid, and De Strooper said the drug proved effective at clearing it but also had “beneficial effects on other hallmarks of Alzheimer’s, including tau”.

The phase 3 trial involved nearly 1,800 people, divided between those given the drug and given a placebo, and ran over 18 months.

They were assessed on a clinical scale for Alzheimer’s patients that measures cognition and function, as well as for changes in amyloid levels and other indicators.

Tara Spires-Jones, program lead at the UK Dementia Research Institute, noted that “there is not an accepted definition of clinically meaningful effects in the cognitive test they used”.

“It is not clear yet whether the modest reduction in decline will make a big difference to people living with dementia. Longer trials will be needed to be sure that the benefits of this treatment outweigh the risks,” she added.

The drug also only targets those in the early stages of the disease with a certain level of amyloid build-up, limiting the number of people who could potentially use the treatment.

And as Alzheimer’s is not always caught quickly, some experts said an overhaul in early diagnosis would be needed to ensure more people could benefit.

“This isn’t the end of the journey for lecanemab — it’s being explored in further trials to see how well it works over a longer period of time,” said Richard Oakley, associate director of research at the Alzheimer’s Society.

“The safety of drugs is crucial and lecanemab did have side effects, but they will be closely looked at when decisions are made about whether or not to approve lecanemab, to see if the benefits outweigh the risks,” he said.

Biogen and Eisai previously brought the Alzheimer’s drug Aduhelm to market, but there was significant controversy over the evidence that it worked, and its approval led to three high-level resignations in the US Food and Drug Administration.

With AFP