Gilbert McAdam: ‘When we played, it was basically anti-indigenous round every week’

Gilbert McAdam was right alongside Nicky Winmar for one of the most important games in AFL history in 1993. But he said the abuse the pair copped from supporters, and even players, that day was enough for his father to walk out on the historic moment.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

I was listening to David Letterman and Barack Obama talking about racism recently. Letterman said, “We can define racism. But we can’t explain it”.

The former US President responded with something like, “People come up with all sorts of reasons to try and put themselves over others, but biologically, there is no reality to racism — we made it up — but over time it manifests itself in very concrete ways and becomes a social reality, with very real impacts”.

It simplified a terrible part of humanity.

So many have endured atrocities committed towards them, simply because of the colour of their skin or their place of birth. Gilbert McAdam is one.

You may know him from his deeds on the football field. He was a hell of a footballer — but that’s just a small part of his story.

He is the grandson of a wealthy white man. He has seven kids. He has lost two brothers. Many of his family still practise Aboriginal law.

He is one of the most thoughtful, kind and gentle men I have met. But sadly, too often in his life, he has been treated horrifically.

HM: Gilly, you were born in Alice Springs. What did your old man do?

GM: My father was a horseman. He was born in a place called Springvale Station, about 50km out of Halls Creek. My dad grew up out bush and was working from day one. He’s just done that all his life, and he ended up being a manager at a few big stations over the years. That’s what my dad used to do, and eventually he made his way to Alice Springs, and brought up 10 kids.

HM: He had 10 kids.

GM: Yeah … it’s a big family. Two of my brothers died — there’s eight alive now. Four boys and four girls.

HM: How did your brothers pass away?

GM: They’re both sad stories. One of them, Graham, died when he was just a baby, and there were about 10 babies that ended up dying at the same time in the area with a similar complication. The other brother, Elliott, was about 10 years old, and he bloody walked out to a bus when a car came and he got run over, the poor little fella.

HM: God, I’m sorry. How terrible.

GM: Yeah, bloody horrible. Hard to imagine it.

HM: Your dad, Charlie, was forcefully removed from his mum when he was just six years old?

GM: Yeah, he was. Back in the day, when my dad was born, my family and I were Kija, which is our tribe in the Kimberleys. My dad, and my grandmothers and grandfathers, they walked the country, and because the cattle station was built on our country, what had happened is all of my family worked at that cattle station. My nana was a cook, and what happened then was the bloke who owned the station, Jimmy McAdam, mucked around with my nana, and that’s how my father was born. My dad’s father was white.

HM: I had no idea about that.

GM: It’s an amazing story, Hamish — it really is. My dad actually wrote a book called Boundary Lines that talks through it.

HM: I’ll grab a copy.

GM: Then my dad was sent to an institute in WA. The state government used to round up all the half-caste kids, all the kids that had a bit of white in them, and take them. They didn’t treat them too well, to be honest. Any kids out bush that had a bit of white blood in them. Thank goodness the Catholics got involved and ended up taking over from the government. He was then moved to a place called Beagle Bay down near Broome.

HM: That’s hard to believe — it’s so recent.

GM: I don’t say much about it because you try and move on, but it’s amazing how my family came to be. My grandfather, Jimmy McAdam, used to own the Katherine Pub and the Wyndham Pub. He was white — and a Scotsman, that’s why we got the name McAdam. My grandfather was a very, very wealthy man.

HM: Amazing.

GM: It’s an incredible story, mate. I don’t know whether you’ve seen Rabbit Proof Fence — but that’s basically my dad’s story, brother. Dad was taken away in the late ’30s. That’s only one generation from me. A lot of people in Australia don’t understand that sort of stuff until people like me tell the story. They don’t get taught that, and Aboriginal people have had a lot of hard times over the years, you know. That’s why we are the way we are. We are very resilient people.

HM: Your dad was born under a tree, wasn’t he?

G M: He was. He was born under a bloody tree, brother. A paperbark tree. When my dad wrote that book, it affected me that much that I gave the game away. That’s why I retired so early. I was ready to sign another two-year contract. My dad didn’t tell us that story until later on in his life, and he kept it a secret. He just didn’t want to talk about it.

HM: Why?

GM: He just didn’t want to talk about it, and just didn’t say anything. As we got older and we found out the full story, we put pressure on Dad, and told him to write a book. He had to tell his story. He wrote the book, and then before he died, I went back to the station with him, he showed me the tree where he was born, and told me all the stories there. Dad and Mum have passed now, but Dad lived a pretty hard life. They were pretty cruel back then — they used to flog them and everything.

HM: Where were you brought up?

GM: Dad had all us kids on the cattle station. My dad went to school after he was taken, but he ran away and made his way back to Springvale Station, which he loved. Eventually he was working outside of Alice Springs Station, where he met Mum — and 10 kids later.

HM: What is your mum’s background?

GM: My mum is an Arrentre lady. Our family connection is very strong because my people still go out bush and still practice Aboriginal law.

HM: What is Aboriginal law?

GM: They call it customary law too. It’s the law our people have developed over time from our way of living that runs our people and connects our people with the land and with each other through relationships. It’s not written anywhere — it’s all passed down by word of mouth. In 2019 they still do it, for five months, six months, and tell them all the stories. They still do all that.

HM: Wow.

GM: My brothers Gregory and Adrian have actually been through Aboriginal law — they take their sons out as well and teach them the Aboriginal ways.

HM: I’m learning a lot today, Gilly. I was reading about Nicky Winmar, who was a teammate of yours at St Kilda. He grew up in a tin shack without any running water and a bucket for a loo. Where were your conditions growing up?

GM: We were lucky — my father was a hardworking man so we were lucky to always have a feed and a roof. My father was a workaholic, and he just worked so hard, Hamish, so he always had some money to look after us. When Mum and Dad were living out in the bush, on the cattle station we always had a home.

HM: Ten kids. And how many ended up playing AFL/VFL? Three of you?

GM: There was three of us. Greg, the oldest one … he went to North Adelaide and then the Saints. And Adrian played for the Kangaroos. Greg’s the one that got us started, because they recruited him when he was only a young fella as well. Remember Northfield High School?

HM: Yes.

GM: Greg got recruited at a young age and they put him through school, which is exactly what they did with me. Eventually when they wanted to get Adrian, Mum just said, “No. I’m moving to Adelaide”, so Mum ended up moving to Adelaide. That’s how it all started.

HM: When did you first get a football in your hand?

GM: Probably when I was about five years old.

HM: You got bloody good bloody quickly.

GM: Well, when I was only 10 years old, I was picked in the Australian Championships in under 12s. I played three years a row in that team.

HM: And you were captain in grade 7 of the Northern Territory team, and you won the Championships?

GM: We beat South Australia by one point at Adelaide Oval in 1979.

HM: The Northern Territory team had never won the championships?

GM: That was the first time ever, and Cyril Rioli’s dad played in it — Cyril senior was kicking 50 metres when he was 12 years old, that bloke. He was amazing.

HM: How old were you when North Adelaide recruited you?

GM: They grabbed me when I was 14. Greg was already there. North Adelaide recruiters saw me play in that carnival at Adelaide Oval in the under 12s. They said to Greg, “Well, we’ll take your brother as well — get him down here too.” I wanted to go, you know, because I wanted to be like Greg. Greg was my idol.

HM: Most little brothers look up to their big brother.

GM: Greg was able to come out of Alice Springs and make it as a footballer … no one had done it. He really put Alice Springs on the map in a footy sense, my brother Greg. He was a best and fairest player at North Adelaide in 1979, played for St Kilda and played state footy too — he was a pretty good player.

HM: And then at 14½ you train with the senior team?

GM: I started in under 17s. I was too skinny, but they didn’t worry about it. They said, “You keep training, go to school, and you’ll be all right; you’ve just got to be patient”. Eventually I played U/17s but I was homesick and I went back to Alice Springs and played there. Then I went up to Darwin to play and then Claremont recruited me from there.

HM: You went to Claremont, and then from Claremont, Central District rang and said we want you?

GM: I went back home and then I said to myself, I need to go back, so I made a big decision and went straight to Adelaide. Neil Kerley had just got the coaching job there, and I said to myself, this bloke will bring the best out of me. That’s exactly what happened. He gave me an opportunity and made me the best player I could be.

HM: In the late '80s, the SANFL was as strong as it had ever been — and the Magarey Medal was the equivalent of the Brownlow. You were 21 in 1988 — how did you go?

GM: I was runner-up — that was my first year in the SANFL. It had a lot to do with Neil Kerley. He was the one that brought the best out of me, and he just let me play the way I wanted to. He didn’t stop me from using my skills and all that sort of stuff, he just let me play the way I played. He gave me that much confidence that once I was believed I was good enough, and once you believe you can beat anybody, that’s it. You’re on your way.

HM: How’d you go the next year in the Magarey Medal?

GM: I won it the following year.

HM: The first indigenous player to ever win the Magarey Medal.

GM: Yep. The first one. A proud moment, brother.

HM: Huge. From Centrals to the St Kilda. Did they look after you?

GM: They did. I’d just won the Magarey Medal, they gave me a fair wage, and I bought a house in Dingley. They gave me some money upfront, and I went and got a loan from the bank and I bought a house. I couldn’t believe it.

HM: They helped you set your life up?

GM: It should have, but I went through some other stuff and I haven’t got it anymore. It would have set me up for life, don’t you worry about that, because I bought that house for $140,000 at the time. It’s probably worth $1 million today. Bugger it … anyway, I’ve moved on from that.

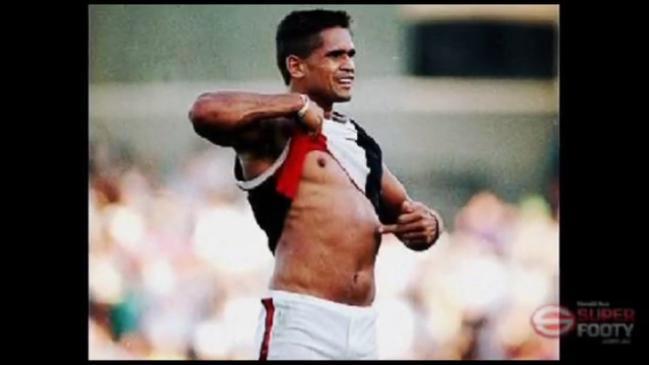

HM: Seemingly … While at the Saints, you played in one of the most important games in football’s history, for various reasons. Round 4, 1993. St Kilda versus Collingwood at Victoria Park. The famous game where Nicky Winmar lifted his jumper and said, “I’m black, and I’m proud to be black.”.

GM: I didn’t realise how much that game would go on to change the face of football. I had no idea — even leaving the ground.

HM: What happened when you and Nicky, walked up the race at halftime of the reserves match to go out onto the ground and get a feel for the surroundings?

GM: At Victoria Park, when you were in the visiting rooms, you’d come out of the race, and you’d be hit by the Collingwood cheer squad. They were in your face straight away. As soon as we walked out, they were calling us everything under the sun and spitting on us. I don’t like talking about all that sort of stuff, because I’ve moved on from it. They were calling us everything, mate, but I don’t actually like talking about what they said.

HM: You suffered the abuse, got to the middle of the ground, and grabbed Nicky Winmar. What did you say to him?

GM: I just said to him, “Me and you have got to get best on ground today. That’s the only way we can stick it up them, is to win the game. And you and I need to lead the way”. And that’s exactly what happened.

HM: Who got the Brownlow votes?

GM: Nicky got two. He was incredible.

HM: Who got three?

GM: Me. I kicked five before three-quarter time. They were the first Brownlow votes I ever got.

HM: Your dad, Charlie, was at the ground, he’d come down from Alice Springs, and he walked out of the ground crying.

GM: He had to walk out because of all the abuse they were yelling at me and Nicky. He couldn’t stomach it anymore. He would have ended up killing someone, or they would have killed him. He just couldn’t handle it, so the best way to handle it was just to walk out and go home.

HM: Sad he couldn’t see his son and his indigenous teammate dismantle a side on their home deck and witness such a huge moment because his son and his mate were being racially attacked.

GM: I wish he could have seen it. He would have been proud of us I reckon, brother.

HM: Was the abuse from just the crowd, or the players too?

GM: Mainly the supporters. A few players back then that used to say some stuff, but I don’t like mentioning their names. It was the way it was. Just because it was the way back then, it didn’t mean it was right. I don’t want to embarrass the players by naming them either — even though the things they said were bloody bad. We copped it from the players, all right.

HM: You won — and when the abuse that was being hurled heightened, Nicky took a stand. How far from him were you when he started blowing kisses to the crowd?

GM: Well I didn’t even see that happen — I was too busy giving the St Kilda supporters high-fives. We were so excited that we won the game, it was the first time we’d won there since the '70s.

HM: 1976.

GM: Because we’d won the game, the passion spilled over, I was just so excited that our little group of supporters were all so happy. I didn’t realise what Nicky had done until the next day when it was in the paper. That’s how we all found out, and then everyone started ringing the club about it wanting to speak to us.

HM: A most iconic moment captured perfectly by photographer Wayne Ludbey — and the picture was on the front page the next day.

GM: What an image, hey. A proud indigenous man, who had just spent two hours listening to abuse, but who had triumphed, standing tall and proud and defiant. Wow.

HM: It was a beautiful and significant moment in time. The club banned you from speaking about it, didn’t they?

GM: They did. It was a really touchy subject back then. I could understand where they were coming from, in a way, but back in the old days a lot of stuff was just swept under the carpet. That’s just how it was. The next day they just didn’t want us to talk about it.

HM: Were you subject to racist taunts every time you played?

GM: We copped it a lot — we copped it every week from the supporters. When we played, it was basically anti-indigenous round every week. Looking back, it’s amazing to think it was considered normal or OK.

HM: It was only 25 years ago or so.

GM: It’s true, mate. That’s why these young fellas today, when they cop abuse, they are comfortable now to call it out. And racism at the football now is taboo — as it should be everywhere in society. I’m so happy for them, because we weren’t in positions to do all that in our day.

HM: If you’d spoken out back in the day, what would have happened?

GM: I don’t know. It’s a good question. We didn’t say much. We didn’t think we had a voice.

HM: You didn’t feel confident enough to speak up?

GM: Maybe. I was trying to establish myself at the same time, even though I was probably already established. Sometimes I can’t explain it. I think the more you spoke about it, the more it hurt you. You just wanted it to go away. But I also think there was also a feeling nothing would change.

HM: How often are you subject to racism now?

GM: I was in Shepparton the other day grabbing a beer with a good mate of mine, Peter Cardamone, and this old bloke nearby said the word, “n---er”. That happened three weeks ago. I pulled him up and said, “What did you say, mate?” He said, “Oh, you don’t like that word?” I said, “Mate, you just don’t say that word today. You should never have, and you shouldn’t now — not in 2019.”

HM: And in what context was he saying that to you?

GM: He was talking about Marngrook, the footy and all that, and he just came out with the word. N---er. I couldn’t believe it.

HM: Unbelievable.

GM : I was that dumbfounded by what he said that I couldn’t believe it. My mate looked at me and I just said, “Mate, let’s get out of this pub. I don’t want to stay in here and listen to sh-- like that”. We left straight away. When you’re a blackfella, you come across it all the time, mate. Any time. It’s not as bad as it used to be … but you know it’s around the corner, sadly.

HM: Even as far as we’ve come, is it still complicated for an indigenous man living in this country.

GM: When I went to Adelaide to school at the age of 14, I copped it at school straight away. I had a fight in the first week. In under 17s, in my first game, I copped it straight away on a football field, and I copped it in the shopping centres, and I still do today having a beer. Many non-Aboriginal people don’t understand where we have come from — and that’s why I get really upset when some people say, “Just get over it”. You can’t get over it, because you’re always being judged as a blackfella. That’s just the way it is. I can’t say it any other way.

HM: When you walk into a room now, and when you and I work together at the MCG on a Sunday afternoon, do you feel as though people are looking at you differently to how they look at me or BT or Jimmy Bartel?

GM: I still do a little, yeah. I treat people on their merits. If you’re good to me, I’ll be good back to you. That’s it. If you’re bad to me, then I’ll just ignore you. I wish life was like that both ways.

HM: Have you learnt to ignore racists? Does it still affect you?

GM: Not as much as it used to. I got pretty angry in Shepparton the other day though.

HM: It must make you proud when you look out on the ground now and see the best players are often young indigenous men.

GM: And there’s so many. Every team’s got them, and it’s not just one or two, it’s three or four. I get really proud when I see that.

HM: You’ve got seven kids, and you’re living now in Melbourne — your job is mainly in the media?

GM: Yes — I do the Marngrook Footy Show, I do broadcasts for radio with National Indigenous Radio Service, and I just got a job at SEN now every Thursday, for 40 minutes. A bit with Channel 7, and I get a few speaking gigs too.

HM: Are you enjoying Channel 7?

GM: I’m loving it. I feel very privileged that they’ve given me the opportunity. And I love Marngrook. It’s just great having the indigenous girls on there talking as well. It’s a great medium for non-Aboriginal people to see us do what we do.

HM: You’re pretty relaxed about things. You and I were on air the other day, for two segments, or about 18 minutes, and you said to me, “When are we going live?’

GM: (laughs) I know … I didn’t realise that it was going live … That’s just how I am.

HM: Was that the same day you forgot your shoes, and you wore your sandshoes, and now you’ve got a sponsorship deal with Adidas?

GM: (laughs) Yeah … it’s funny how things work out, isn’t it? The boss at Seven said, if you are comfy in them, wear them, make it your thing. So I will. I’m working with Leigh Matthews this week — you don’t get to work with people like that every day, so it’s a pretty special moment for me. I hope he doesn’t ask me, “Why are you wearing your sneakers?”.

HM: Leigh, or “The Statue” as we call him, will be jealous. Gilly, of all the lessons you’ve learnt, what’s the one thing that you could pass on to those that are reading?

GM: Learn the history of our people, where we’ve come from, and how far we’ve come. I don’t dwell on the past — that’s the way my father and my mother brought me up. My parents were very hard, but fair. There are a lot of Aboriginal people who don’t like white people because of what they’ve been through, and we were never brought up like that. We were always brought up to be good people who treat people the way you want to be treated. I hope everyone can look at people for who they are — and not the colour of their skin.

HM: We didn’t get to Ash Barty.

GM: How good that there is an indigenous Australian that is the No. 1 tennis player in the world right now? That’s deadly. It makes me so proud, but do you know what makes me even prouder? She is recognised, she is Aboriginal, and she’s a proud Australian that’s indigenous. That’s what I love most about it.

HM: She’s a beauty — so are you. Thank you.

GM: No worries, brother.