Food allergies: the rise of the modern epidemic

IN a generation, food allergies have gone from the exception to being the rule. Medical reporter Lucie van den Berg investigates this modern epidemic.

Food

Don't miss out on the headlines from Food. Followed categories will be added to My News.

JETT’S little face was so swollen it looked as if someone had blown his head up like a balloon. The puffiness forced his eyes shut and as his throat constricted, the then two-year-old started vomiting.

But it was the sound coming from her baby boy’s chest that was the most terrifying for his mother Kaylee Muse.

“The noise, oh,” she pauses and shudders as if she’s back in her son’s bedroom. “It was horrible, he was gasping for air, it sounded, like death.”

The culprit? A half-eaten Easter egg sitting in the corner of the room. That innocuous ball of chocolate goodness, smuggled home by a big brother desperate to indulge, could contain cow’s milk, egg or peanuts, each one capable of killing the now eight-year-old Jett.

This horrifying episode has never been repeated in the Muses’ Mernda household. This is largely due to mum Kaylee treating each day like balancing a seesaw — on one end sits her children’s safety and the other, their quality of life.

Three of her Kaylee’s five children have food allergies and it takes a peanut-free household, two ovens, two sets of cooking utensils and meals that are entirely homemade to keep her children safe. Eating out is practically impossible and a bake-off is required before they go anywhere.

It’s a similar story for five-year-old Nicanor Martell.

He can only eat food made by his mother Dedrieia Tull because he is allergic to wheat, rye, eggs, cow’s milk, bananas, salmon, almonds, avocados and sesame.

Dedrieia jokes about owning the biggest collection of cookie cutters in the country.

“I use them to make biscuits or tarts and cut them out in interesting shapes,” she says. “If he feels he is having fun food then hopefully he is less tempted to try something that he shouldn’t.”

Even though their diets appear restrictive, parents of children with food allergies say their children eat a wider variety of foods than most because they are forced to. Kaylee uses cauliflower to make doughnuts, broccoli for spaghetti and cacao for chocolate. Oranges have become target practice for adrenalin shots, her child’s only lifeline in the event of anaphylaxis.

“Here, at home he is safe,” she says. “There is nothing that can kill him.”

MODERN DILEMMA

STORIES like this often prompt puzzled responses from adults who never knew anyone with a food allergy when they were growing up. Now it feels like they are everywhere.

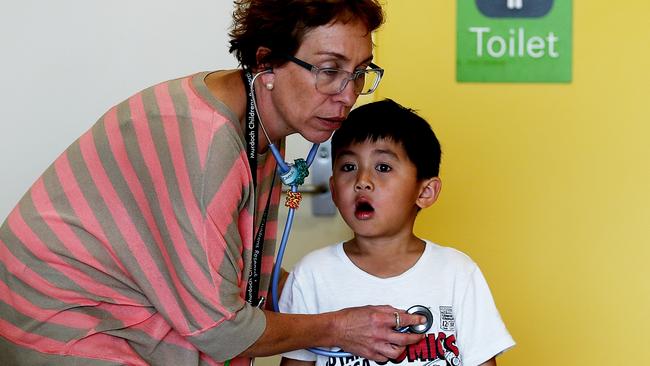

Murdoch Childrens Research Institute and Royal Children’s Hospital’s Professor Katie Allen is one of the country’s foremost allergy experts and remembers her first research grant application to study food allergy prevalence.

“We actually wrote in the original grant application that it could be a ‘media beat-up’ because we wanted to be even-handed and let the evidence speak for itself,” she says. “We estimated it could be as high as 1 per cent of people had a food allergy, but we were blown away when it was 10 per cent.”

Though there will always be a minority of people who deny the existence or severity of food allergies, dismissing it as a byproduct of paranoid parenting, the scientific evidence, the spike in hospital admissions and the deaths cannot be ignored.

Now it has become a question of why?

FOOD CHALLENGES

INSIDE the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute a polite little boy who says he wants a cloud for Christmas is staring warily at a tub of peanut butter.

How do you explain to a six-year-old that he will now need to eat food he has been trained to avoid?

Evan Chu used to shed so much skin from his severe eczema that his mother had to change his sheets daily.

He is also allergic to cow’s milk and peanuts and today it’s the nut allergy that will be tested in a food challenge.

As the nurse moves the peanut butter closer, Evan’s lips screw tighter together. His mother Cassandra nods and murmurs words of encouragement, which act as some sort of maternal aircraft marshalling that coaxes Evan into eventually allowing the nutty spread into his mouth.

It will only take the tiniest taste, one 16th of a teaspoon, before large red welts break out on his face.

The food challenge is over. Nuts! Evan is still allergic them.

Research nurses Helen Czech and Leone Thiele have seen almost every reaction imaginable during the thousands of food challenges and skin prick tests they perform as part of HealthNuts, the world’s first population-based food study.

The one-year-olds were the worst, with their propensity to paint the clinic with projectile vomit after eating tiny pieces of egg.

“They sneeze, their noses run and they vomit, they just have gunk coming out everywhere as the body tries to rid itself of the allergen,” Leonie says.

Those babies are now six and still being studied. They have helped uncover vital clues that are helping to find ways to prevent and treat allergy.

FIRST 1000 DAYS

THE cause of the rise in food allergies is contentious.

Allen says it’s most likely a result of our modern lifestyle.

“The reason we say that is it can’t just be the genes because they don’t change that quickly so it has to be something in our environment,” she explains.

It may be an increase in antibiotic use, a cleaner environment or a change in the bugs that we carry. Having a pet dog or older siblings appears to be protective, but it’s not clear why.

Many scientists subscribe to the theory allergies are caused by an interplay between genes and the environment.

Epigenetics is the process that turns genes on and off in response to triggers in the environment — for instance air pollution, tobacco smoke or chemicals in the food and water.

MCRI scientists are trying to pinpoint gene disruptions that occur, possibly as early as gestation, in children with allergies.

It ties in with the popular theory that the first 1000 days of a baby’s life can shape their lifelong health outcomes.

“It’s the hot topic of the century,” the RCH’s department of allergy and immunology director Professor Mimi Teng says.

“What we now understand is that all of the diseases associated with modern lifestyle, including allergies, can be linked to the events that occur in your life in the first 1000 days from the time of conception through to the end of your second year of life.”

A very important part of this is the formation of a child’s gut microbiota, the bacteria that lives in the intestines, which seems to play a vital role in modulating immune responses involved in allergic reactions.

“The microbiota is established from the moment you are born — the first bacteria seed the gut and they determine the pattern for the rest of your life, ’’ Prof Teng says.

A pregnant woman’s diet, exposure to the mother’s bacteria in the birth canal and what a child eats in the first two year’s of life may all play a part.

Allen recently carried out Australia’s first gut microbe transplant; replacing a child’s bad gut microbes with his father’s good ones to help him tolerate soy and cow’s milk.

Some companies are even developing “poo pills” to help get some of the good bugs back in the gut.

“In the past we have said that all bugs are bad, but now we are realising that they are not all bad and we need the good ones to stimulate our immune system,” Allen says.

SUNNY SIDE UP

THE second major hypothesis concerns the lack of exposure to vitamin D in this sunburnt country.

Children from the HealthNuts study showed those lacking vitamin D were three times more likely to have a food allergy. And the further from the equator people live, the higher the rates of food allergy.

The vitamin D deficiency debate may also account for why babies born to Asian parents are more likely to develop allergies in Australia where they are exposed to less sunshine.

In a few weeks Allen and her team will begin giving children vitamin D to see if it can prevent them developing food allergies.

One of the biggest buzzes in medical research surrounds trials that do what was once unthinkable — feed people food they are allergic to as a treatment. Could one peanut a day really take the allergy away?

Standford University’s Associate Professor Kair Nadeau certainly thinks so. The US specialist is one of the leaders in the field of oral immunotherapy.

Her trials involve giving children tiny regular doses of their allergen in a strictly controlled environment under medical supervision to see if it desensitises them.

The results are mixed and the studies small, but some children can now eat foods that they were once allergic to though only if they eat small amounts regularly.

In Victoria, Teng is aiming for tolerance rather than just desensitisation in her world first trial.

She is giving peanuts and a special probiotic to children to get their immune systems to tolerate the allergen. The results could revolutionise allergy treatment.

Another promising trial at The Alfred hospital and Monash University is using tiny fragments of the peanut protein to create a vaccine that could protect against the nut allergy.

The proteins are big enough to interact with the immune system and build tolerance, but not so large that they would spark anaphylaxis.

Moves are also under way to prevent allergies by reintroducing the tuberculosis vaccine.

The Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccine was given routinely in Australia until the 1980s when tuberculosis was virtually eradicated. MCRI, the University of Melbourne and Mercy Hospital researchers believe the vaccine could act as an anti-allergy jab that sets the immune system off on the right path, making it more effective at fighting infection and less prone to allergic disease.

IT BEGINS AT HOME

FROM a parent’s perspective the prevention messages have changed as new research emerges.

For a long time pregnant women were told to avoid common allergens such as peanut butter and eggs. And new mums were encouraged to breastfeed exclusively for six months, delaying potentially problem foods until their children were two or three.

But that advice has been reversed on the back of new evidence. It’s now thought that by feeding children small amounts of these foods between 4-6 months it can train a child’s immune system to tolerate the problematic proteins in the food and prevent reactions later in life.

However, Allen cautions parents against blaming themselves for avoiding these foods because even this could not entirely explain the allergy increase. “I mean, children don’t eat shellfish in their first year of life, yet we still have seafood allergies.”

Breast milk is still considered best, but it’s unclear if it is actually protective against allergies with some evidence suggesting otherwise.

The interplay between eczema, asthma, hayfever and food allergies is also being investigated. It’s suspected that babies become sensitised through the skin to allergies because they have a poor skin barrier.

Another Victorian trial is trying to determine if a special cream can prevent the sensitisation.

Anaphylaxis Australia president Maria Said supports the research, but knows there is still a way to go before there will be a viable treatment or even a cure.

“I was told a cure was seven years away when my boy was three, he’s now 24,” she says.

In the meantime she says there is an urgent need of a national registry of anaphylaxis deaths and severe reactions and to give families faster access to allergy specialists. Food labelling, which should have liberated families has actually left them more confused with “may contain” plastered on every second form of packaged food.

In the meantime, families who are affected will arm themselves with Epipens and continue to do whatever they can to keep their children safe.

WHAT WE KNOW

● Pregnant and breastfeeding women do not need to avoid foods that commonly cause allergies.

● Mothers can introduce solids, including high-risk foods such as peanuts and eggs, to their babies’ diet when they are 4-6 months of age instead of delaying it.

● Having a pet dog and older siblings may reduce the risk of food allergies.

● A lack of vitamin D may be linked to the rise in food allergies.

● People who migrated to Australia from developing countries have a higher risk of eczema and food allergies.

● Children who can frequently tolerate small amounts of eggs in baked products are three times more likely to grow out of their allergy.

● 80 per cent of children will outgrow egg and cow’s milk allergies by the ages of 5-10, while only 20 per cent will shake their peanut and shellfish allergies.

HOMEGROWN RESEARCH HOPES

● A trial giving children with peanut allergies

a special probiotic and tiny doses of the nut to help their immune system tolerate the allergen.

● Testing babies to see if there are factors that regulate genes that may predispose them to developing allergies.

● Giving newborn babies the tuberculosis vaccine to see if it can boost a child’s immune system.

● The country’s first gut microbe transplant in an infant was carried out to replace a child’s bad gut microbes with good ones to induce tolerance to foods.

● Giving children vitamin D supplements to see if it can prevent allergies.

● A vaccine made from tiny fragments of the peanut protein that are big enough to help build tolerance, but not large enough to cause anaphylaxis, is being developed.