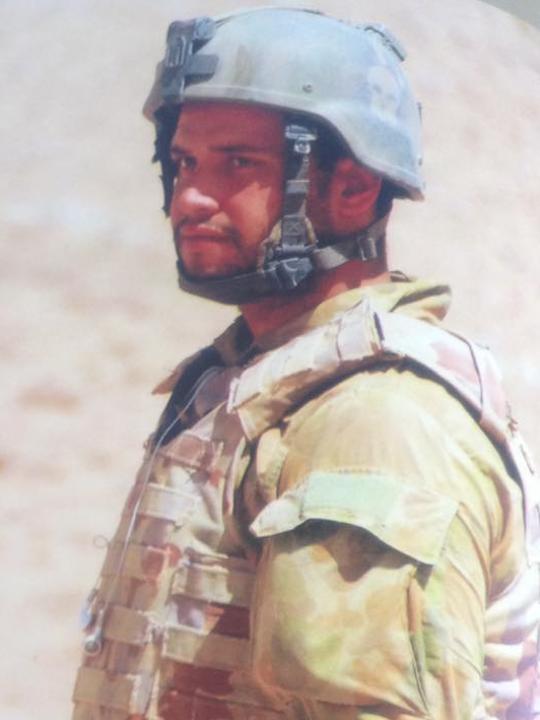

Boronia Digger Phil Hodgskiss on death of friend and veteran Jesse Bird

A DIGGER from Melbourne’s outer east has opened up about life after war after the suicide of his mate, a fellow former soldier who served in Afghanistan.

Outer East

Don't miss out on the headlines from Outer East. Followed categories will be added to My News.

YOU hear an explosion 100m down the dirt track you’re patrolling, and as you turn the corner the bloody remains of your enemy are a stark reminder you and your mates narrowly survived.

These threats became reality of life on deployment in the valleys of Afghanistan’s Oruzgan province — leaving Diggers with an anxious buzz that developed into the daily norm.

Veteran Jesse Bird, who took his own life, spent years asking for help, says mate

This meant coming home would prove far harder to handle for veterans like Jesse Bird, who returned from overseas with scars far deeper than any medic could heal.

Jesse was Phil Hodgskiss’ mate and fellow vet of almost 10 years when the 32-year-oldcommitted suicide on June 27.

Mr Hodgskiss, from Boronia, said 33 veterans had already committed suicide this year, but Jesse’s death was particularly hard to deal with.

“He was the first one in my immediate group of friends, which is probably why it’s hit so close to home,” he said.

“This is the one who has been truly close to me.”

Phil said Jesse had tried for seven years to get the Department of Veterans Affairs to recognise his mental scars from battle, but it was all in vain.

“The nightmares he was having, from what I’ve been told, were incredible,” Phil said.

“But in the end what killed him was the rejection, having this government body that’s charged with supporting our veterans, turn around and say ‘no, you don’t qualify’.”

The pair was deployed to Afghanistan in 2009, in the same company but different platoons.

Phil served in the heavy weapons anti-armour platoon in what was his second trip to the country.

Jesse was as an assault pioneer on his first deployment since joining the infantry in 2007.

“I think mentally the second was a lot more challenging or stressful … especially with the counter-IED (improvised explosive device) operations,” Phil said.

“It’s mentally challenging to think you’re waking up in the morning and you’re being told go walk through the valley, with the idea of stumbling across an IED hopefully before it goes off.”

Phil was there for seven months, left the army in December 2011 and now works in healthcare.

But for Jesse, the deployment changed his life.

“I don’t know if desensitising is the right word, but what happens is, your norm changes,” Phil said.

“If you were to walk down Main St, Croydon, and a bomb went off and there was legs and guts dripping from the trees, that’s not normal.

“But you go downtown Kabul in 2007 and that’s pretty much stock standard.”

He said many vets came unstuck trying to readjust to normal life and to rationalise what they’d seen and felt.

“It’s incredibly frustrating because the things that matter over there don’t matter over here,” he said.

“Over there if you don’t fill up your water bottles before a patrol, if you run out of water, you have to ask your friend for theirs and that means they have to give you their water which is sustaining their life.”

But on the flip side, little things that used to matter, before Afghanistan, don’t anymore, he said.

“When I came back and was stuck in Melbourne traffic people were raging out because they wanted to get home,” Phil said.

“I’m like, no one’s trying to kill me, I know at some point I’m going to get home, and there’s a better than average chance I’ll do it safely, and none of my friends are going to die in the process.”

If you need help, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636.