Future of private maternity in Australia under ‘serious threat’

The future of Australia’s private maternity system is “under serious threat”, with 18 units closing across the country in seven years. Here’s the latest.

Pregnancy

Don't miss out on the headlines from Pregnancy. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The future of Australia’s private maternity system is “under serious threat” amid 18 units shutting in seven years, with doctors warning it will result in poorer health outcomes for mums and babies.

The staggering figure provided by the National Association of Specialist Obstetricians and Gynaecologists includes upcoming closures in Hobart and Darwin.

Provider Healthscope has blamed staff shortages and declining birthrates.

Specialist obstetrician and gynaecologist Kirsten Connan, who works out of Hobart Private Hospital, said there was deep disappointment in Tasmania.

With 18 private maternity wards shut or shutting across the country since 2018, she said the Australian population “deserved better”.

“We really need to be careful we don’t lose private maternity care in Australia because it will be worse for women and their families around health outcomes for mums and their babies,” she said.

“(Unless something changes) effectively maternity care in the private sector will become exclusive with an incredibly high fee and only available in major metropolitan cities on the eastern seaboard in Australia … everywhere else it will fall apart.”

Dr Connan said they had been working toward a solution where the Calvary maternity service in Hobart could take on the extra births.

It currently has a capacity for about 350 births a year so would have to expand to pick up 500 that were happening at Healthscope.

“That comes with challenges we are yet to overcome,” Dr Connan said.

‘It was such a shock’

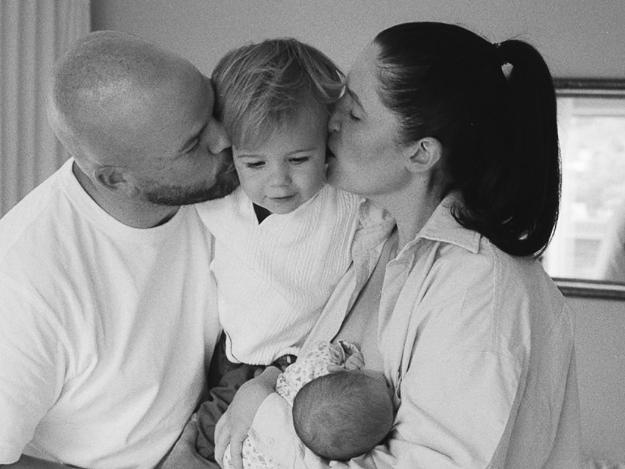

A mother who had her first two babies at Hobart Private Hospital fears that a pregnancy condition she suffered with both children could have been missed if she went through the public system.

Kate Stephens had her second baby Poppy, now six weeks, shortly before the closure was announced.

“We heard the news and it was such a shock, we would really like a third baby and it made us a bit nervous about what that looks like in Tasmania now,” she said.

“We made the decision we wanted to access the private model of care and have that time in hospital, particularly with our first baby, to find our feet, not feeling like we had to leave by a certain time.

“My friend had to leave in four to 12 hours when she had a baby.”

Ms Stephens said the private health insurance was expensive and she felt lucky to be able to afford it.

“Our public system is incredibly overloaded, I don’t want to add to it unnecessarily,” she said.

She said Dr Connan picked up that she had intra-uterine growth restriction – when a baby in the womb doesn’t grow at the expected rate – with both her pregnancies.

“I’m not confident that would have been picked up as quickly in the public system because I was seeing my obstetrician on such a regular basis,” she said.

Growing ‘maternity deserts’ in regional and remote Australia

Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation federal secretary Annie Butler said the latest closures would reduce the options available for women to access maternity care of their choice, forcing more people into an already overstretched public health system.

“Given recent closures, the ANMF is concerned that further maternity services may be impacted,” she said.

The ANMF said private hospitals were already struggling with midwife recruitment due to challenges like high workloads and lower remuneration.

The federation said it believed private hospitals and governments needed to take action by:

Properly remunerating midwives to reflect their work value and expertise;

Implementing staffing ratios that take into account the care of newborns alongside mothers; and,

Allowing privately practising midwives admitting rights to private maternity services, providing more choices for women and enabling midwives to work within models of care that align with their professional values.

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists said it was “deeply concerned” by the latest slated closures.

“The decline of private obstetrics services deprives women of choice and puts significant pressure on the already under-resourced public system and workforce,”president Gillian Gibson said.

“Women facing high-risk pregnancies or those who prioritise continuity of care with an obstetrician often rely on private maternity services.

“The closure of private facilities exacerbates growing “maternity deserts” in rural, regional, and remote areas, forcing some women to travel hours for essential care.

“Those with private health insurance in these areas find it increasingly difficult to use their coverage.”

She said specialists often left communities as private obstetrics services closed, further reducing access to care.

Dr Gibson said financial disincentives and structural gender biases that undermined private obstetrics disrupted the balance of a robust private sector to support the public system, putting further strain on the latter that was not designed to manage such a demand.

“If this trend continues, it will cost both state and federal governments additional hundreds of millions of dollars, as the public system sees an influx of additional births,” she said.

The college said the future of the private maternity system was currently under serious threat and the federal government and private health insurance providers must come together to reverse the “growing crisis”.

Dr Connan said running maternity care was expensive and not as economically viable for private hospitals compared to other surgical procedures.

“This is a reflection of private health insurance and the challenges that private hospitals have in terms of affordability of running services when the rebate often for women’s healthcare areas, including obstetrics, is low compared to other procedures in private hospitals,” she said.

“It’s really costly running maternity care, if you’re a private hospital it’s much more financially beneficial to offer day surgery procedures, whereas when you give birth you generally stay in hospital for at least two, three, four days.

The Hobart and Darwin announcements have also highlighted tensions between insurers and hospitals.

Health Minister Mark Butler last year flagged the private hospital sector was facing a number of challenges, largely because of “private pressures in the system” that could only be managed by hospitals and insurers “sitting down together and sorting it out”.

He recently directed insurers to increase private hospital funding.

The Australian Private Hospitals Association said it was “cautiously optimistic” about the move.

The federal government also announced it would give $6m to the Tasmanian government to support the expected increase in demand for maternity services across the public and private system.

The NT government announced a package that would see private insurers provide other options for mums.

A federal health department spokeswoman said the government was continuing to engage with the private hospital sector on its long-term viability.

In a budget submission to the federal government, Private Healthcare Australia said midwives, GPs and obstetricians should be able to offer a total package of private maternity services, including pregnancy care in the lead up to birth, with fixed out-of-pocket costs.

The peak body said in response to concerns many Australians were turning away from private hospital maternity services due to factors including high out-of-pocket fees, health insurers wanted to be able to fund more choices, including midwife-led care and GP-led care in the private hospital system.

A Healthscope spokesman said: “We have kept both the NT and Tasmanian governments informed of the respective challenges we’ve been facing in maintaining maternity services at our Darwin and Hobart private hospitals.”

“No other maternity services at other Healthscope hospitals are impacted by these recent announcements,” he said.