How a botched child recovery operation in Lebanon left Channel Nine’s TV empire exposed

KERRY Packer’s directive was once to “just do it and get it right”. But a botched kidnap saga has left Channel Nine’s TV brand exposed more than ever.

TV

Don't miss out on the headlines from TV. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Nine’s internal 60 Mins review raises eyebrows

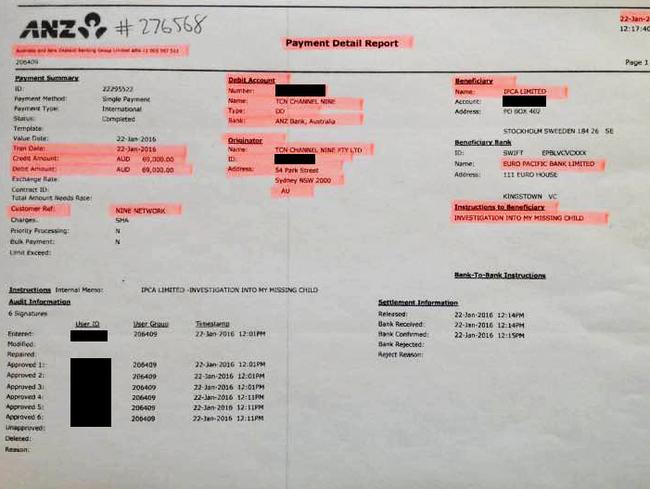

- The proof Nine paid for the snatch scandal

- Nine paid father $500K in kidnap saga

- Nine’s $1m deal - but will it pay off?

THROUGH an open window of 60 Minutes’ unassuming cottage office, in a street backing onto Nine’s Sydney headquarters, the long-term planning for this current affairs flagship is clear for all to see.

Scribbled in red pen on a poster-size whiteboard calendar, the key dates for some of this award-winning investigative program’s biggest stories are there writ large, inked in ahead of the chase.

Court appearances, the Sydney siege inquest, even multiple entries for the filming of this Sunday night’s exclusive story with a Perth family’s miracle quintuplets.

From January to June, there are plotted story points laid bare in such an unsophisticated system of news production likely to give outsiders the first clue to just how an esteemed TV brand like this one could expose itself in the most fundamental processes of journalism the way it appears to have done during its now infamous botched child recovery mission in Beirut.

MORE: Mick Gatto asked to help 60 Minutes crew

From the first explosive CCTV footage of a daring daylight snatch-and-grab operation, involving military-style agents muscling two young children from the grasp of their 70-year-old grandmother and nanny in the heart of Hezbollah territory in South Beirut, this was no longer a well-intentioned custody dispute story but an unscripted nightmare for Nine, its staff and their anguished families.

Within hours of that April 6 kidnap attempt, star reporter Tara Brown, her three-men crew, desperate Brisbane mum Sally Faulkner and the hired guns they paid to seize back her two young children, Lahela, 5 and Noah, 3, would all find themselves behind bars.

What it would take to get the Nine team home free was a compensation deal believed to be about $1 million to Faulkner’s estranged Lebanese husband, Ali Elamine, who claims to have tracked the $115,000 plan to steal back his children over emails synched through the former couple’s joint Apple iCloud account. The equivalent of 60 Minutes’ whiteboard in the sky.

Still counting the cost of the monumental misadventure are expat Australian soldier and one-time Scotland Yard detective Adam Whittington, and his team of Craig Michael, Mohammed Hamza and Khaled Barbour, from Child Abduction Rescue International, who remain in prison, or under police guard in hospital, on serious charges including kidnapping, crime conspiracy and violent assault.

A full internal review — to be lead by 60 Minutes’ founding executive producer Gerald Stone — will now take account, according to a memo by Nine boss Hugh Marks, of “what went wrong and why our systems, designed to protect staff, failed to do so in this case.”

In distancing his network and its so-called ‘Beirut Four’ from wrongdoing, Mr Marks said: “that at no stage did anyone from Nine or 60 Minutes intend to act in any way that made them susceptible to charges that they breached the law or to become part of the story that is Sally’s story. But we did become part of the story and we shouldn’t have.”

‘JUST DO IT AND GET IT RIGHT’

Back in June 1978, when Kerry Packer first offered Stone the job of launching an Australian version of the US original, there were few rules for the fledging 60 Minutes.

Just one blunt directive from the media mogul: “I don’t give a f ... what it takes. Just do it and get it right.”

Those words will have haunted those who found themselves either locked in a Baadba prison cell in the last fortnight; or on the right side of freedom, trying anything and everything to get them out.

As Stone would write in his 2011 book, Say It With Feeling, the weekly long-form show had at its heart, the remit to return with international stories of intrigue.

In delivering them, from all the darkest and most dazzling corners of the globe, no expense was to be spared.

Enter the era of cheque book journalism, when no door could not be levered open with a bag of cash; any headline grabbed at the right price.

Stone’s second-in-charge at that time, Peter Meakin — who has served in executive news roles at Nine, Seven and now as head of news at Ten — scoffs at the suggestion there were many rules of engagement back then, in this new frontier of commercial TV journalism.

“When we went into it, it was a very exploratory exercise ... there weren’t a lot of rules and guidelines. It was a different era, there were a lot more cowboys in those days then there are now,” Mr Meakin said.

Brokering some of the richest deals ever done in Australian broadcast history, he would know the rewards that can come — and may still — for risk-taking, controversial storytelling.

And Nine have bought their fair share.

In 2006, they set the Australian TV record for media deals, securing exclusive interviews with Beaconsfield miners Brant Webb and Todd Russell for $2.3 million.

The price on that survival story — which had played out on air like a soap opera across all channels over the 14-day rescue — had skyrocketed because of the national interest and feel-good factor.

But it would be another cracking international child custody story in the same year which 60 Minutes’ lawyers would deem the most valuable, in case law, ten years later.

In similar circumstances, Canadian mother Melissa Hawach had paid five former commandos to snatch back her two daughters, after their Australian father had fled to Lebanon with them.

Two of the special-force soldiers were arrested and spent nearly three months in prison before they were released; with Nine using the Hawach precedent to argue for Faulkner’s freedom (and by association, the film crew following her).

THE CHEQUEBOOK RATINGS WEAPON

In its recent years, the chequebook has been one of 60 Minutes most powerful weapons in the ratings war.

Last year, executive producer Tom Malone opened Nine’s wallet to secure the extraordinary witness testimonies of six survivors of Sydney’s Lindt Cafe siege for about $1.2 million.

Their cash-for-comment sparked the same debate which surrounds stories like it; with one camp accusing Nine of milking the tragedy, while other viewers accept the lucrative payouts as a reality of modern media, which can ease the financial burden on taxpayer compensation funds and support services.

For almost every dollar spent, Nine won it back in ratings — pipping Seven’s Sunday Night nationally [1.72 million viewers to 1.62m].

While Nine has repeatedly claimed it does not speak about the deals it does for stories, Malone, for example has made exceptions.

Facing almost universal condemnation, Malone went on record no money was paid in the case of another Brown interview with a WA father and convicted paedophile who stood accused of claiming custody of his surrogate baby daughter and abandoning her twin brother Gammy, born with Down’s syndrome, in Thailand.

Malone has maintained his silence since the Beirut arrests, refusing to comment on his role at the helm of the show when the story was first pitched and planned; and again, on January 22, the date on the first cheques Whittington alleges were paid by Nine to his Swedish bank account — two weeks before Malone would relinquish control of the show to his former chief-of-staff Kirsty Thomson, in order to take up his current role as the network’s head of sport.

That regime change was made public on Friday, February 5, with Malone understood to have cleared out his desk that day before hitting the road to meet his new roster of sports talent in Brisbane and Melbourne the following week.

For her part, Thomson had her feet well and truly under the desk by the time Brown, her crew and Ms Faulkner flew into Beirut; and will be answerable for what she knew and approved both as chief-of-staff and the new boss.

Then there’s Nine news director Darren Wick, who returned to Sydney on Thursday, a hero for springing his staff from jail; while playing field producer and chief protector of his network’s exclusive blockbuster Beirut tell-all, now rumoured to air on 60 Minutes next Sunday night.

There’s more than a little irony in the title of the courts where the hearings were held over the last fortnight, the Palace of Justice; a foreboding rectangular box surrounded by curls of razor wire, where sentries watch over everything and everyone from frequently-spaced guard boxes. The assortment of criminals ushered in and out of the building in handcuffs for their court appearances jovially smoke with the captors holding on to their arms.

When a journalist managed to visit detainee Whittington, he had a stark description of the conditions in the small underground cell he was sharing, uncomfortably, with Nine’s male crew.

More than once he mentioned the “rats were as big as cats”. There are indeed both rats and cats visibly probing the piles of rubbish on the streets of Beirut, a city still recovering from a lengthy “trash crisis” after the country’s biggest landfill site closed and garbage collectors went AWOL. Locals are full of stories about how the economy is in the doldrums, not from the pervasive smell from the footpaths, but thanks to the absence of Lebanon’s main big-spending tourists, the Saudis, following a political disagreement.

It’s understated to describe the roads as chaotic, with the rules of engagement in the traffic a secret known only to locals.

Into this world stormed 60 Minutes and the child recovery specialists it had paid to do its bidding.

With all the subtlety of drunken American sailors on shore leave, they snatched the kids and ran. Street security cameras had captured the Keystone cops action and arrests were swift.

From then on, the mission for Nine was to get its team out of dodge.

It was every man and woman for themselves.

While Whittington shared a cramped cell with 60 Minutes, when it came to securing his release, he was on his own.

He knew it too, complaining bitterly that he’d tried to help mum Sally Faulkner get her kids back and now she was “throwing everyone under the bus”.

Nine would leave him high and dry too, abandoning him to fight his own way out of jail, closing its chequebook and leaving on the first flight out of town.

Nine had got its staff out of the jam in the same way it got into it in the first place — by making a large cash payment.

This time the money went to the very man they had no doubt intended to portray to an Australian audience as a heartless child-snatcher, dad Ali Elamine, who had taken his children from their mother and Australian home last May and refused to return them.

On top of that, mum Faulkner had to agree to permanently relinquish custody of her beloved children to secure her own release from prison.

Could it have turned out any worse? Well, yes.

There was always the chance that Nine couldn’t buy its way out trouble, with four of its most experienced staffers staring down charges carrying 20-year maximum jail terms.

It’s a fate which could still await Whittington and his agents, perhaps too easily distracted by the riches pouring from Nine’s deep pockets to consider a more sensible, legal recovery option.

This was a raid that could never have gone ahead without the TV money which funded it (Faulkner just didn’t have the money to pay for such an operation, according to friends).

Discreet payments would have gone some way to distancing the scale of the network’s role in the “kidnapping”.

Then again, there is no sign, even on that whiteboard in the 60 Minutes office, which indicates it ever took seriously the idea of being caught.