Midnight Oil: Adam Goodes, Stan Grant and indigenous leaders in Uluru Statement of the Heart mural for new Oils album

Midnight Oil is releasing its long-awaited new album with a stirring video made by the artists behind an iconic mural of AFL legend Adam Goodes.

Music

Don't miss out on the headlines from Music. Followed categories will be added to My News.

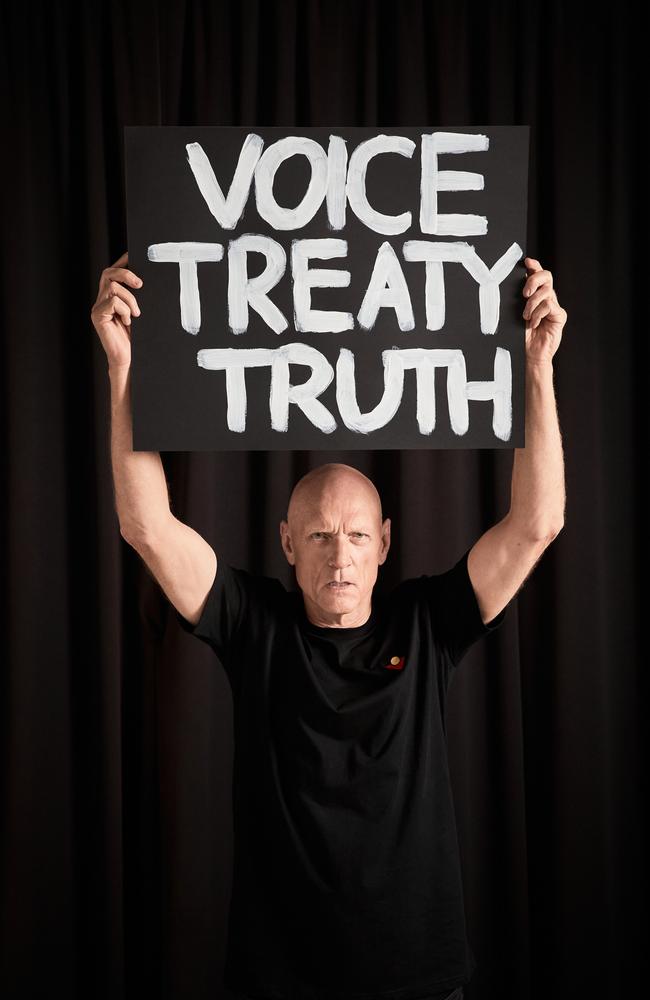

A powerful reading of the Uluru Statement of the Heart has been brought to life with vivid murals of indigenous leaders and artists Adam Goodes, Stan Grant, Pat Anderson and Troy Cassar-Daley for the release of Midnight Oil’s much anticipated new record.

The reading, which also features actor Ursula Yovich, closes The Makarrata Project, which is out today.

The seven-track album, the first new Oils recordings in almost two decades, aims to elevate the historic statement which was presented to the Federal Government but rejected by then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull in 2017.

The real-time paintings of the readers and other images of Australia including the revered Uluru, were painted by artists from Apparition Media who also created the giant Goodesy mural on a building in Surry Hills in June.

THE STUDIO SESSIONS

The primal scream which burst out of Jessica Mauboy surprised everyone in the studio during the Makarrata Project sessions.

She says Peter Garrett exclaimed “Yes! You have to do that again somewhere.”

Mauboy was laying down her vocals on First Nation, the opening track on Midnight Oil’s The Makarrata Project, when her part cockatoo squawk, part horror movie howl, broke out of her after the first chorus.

The Oils’ first recordings in almost two decades are a collaboration with 15 indigenous artists and activists, from the well-known – Kev Carmody, Troy Cassar-Daley, Dan Sultan, Adam Goodes and the late Gurrumul Yunupingu – to the emerging talents of rapper Tasman Keith and singer songwriter Alice Skye.

The Oils intent is to elevate the Uluru Statement From The Heart and to accelerate action on the myriad issues they say governments continue to “shove into the too-hard basket” – reconciliation, Aboriginal deaths in custody, protecting sacred sites from destruction and truth-telling about Australia’s history.

For Mauboy, getting the call-up to contribute to First Nation was a long-awaited opportunity to give voice to the hurt and frustration she felt after then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull rejected the Uluru Statement when it was presented to him in 2017.

“I think the scream came from annoyance at the slowness of how things are moving,” she says.

“I’ve never heard myself sing like this; there’s a layer of hurt and of passion.

“I’m singing in the voice of all the people I’ve met along the way, who have told me their stories.

“My face was just streaming with tears reading these lyrics and that’s how I had to sing it. It’s crying for help, and a battle cry.”

The Oils drummer Rob Hirst recalls another powerful scream which reverberated like a shockwave around the Sydney studio in Botany late last year as the band secretly recorded their new works. Just across the bay where Captain Cook landed in 1770.

Dan Sultan was in the booth adding his parts to the first single Gadigal Land when he stepped back from the mic and unleashed a guttural roar before a blast of horns kicked in.

“Everyone in the studio was knocked over by this wave of 232 years of anger and anguish and frustration that all came out in that one primal scream, it was just extraordinary,” Hirst says.

The songs on the Makarrata Project are as much an emotional outpouring as they are unequivocal protest songs.

There were tears when the band were gifted Lorrpu (white cockatoo), a recording made by Gurrumul before his untimely passing in 2017, to incorporate on the track Change The Date.

The lyrics of all of the songs are among the most direct in the career of a band who have never mixed words or employed metaphor to deliver their message, as evidenced by enduring anthems including Beds Are Burning, the Dead Heart, Blue Sky Mine or Power And The Passion.

It’s one thing for Garrett, Hirst or bandmates Jim Moginie, Martin Rotsey or Bones Hillman to sing them.

But they were aware there may be a spiritual toll on First Nation artists in singing about their shared history of the Stolen Generations, genocide and dispossession of land.

The band, who have been working with indigenous communities since the historic Blackfella/Whitefella tour of remote Central Australia in 1986 with the Warumpi Band, were protective of their collaborators, and gave them free rein on how and what they chose to contribute to the recordings.

“Directness is our thing and that’s what particularly Pete responds to,” Hirst says.

“With my songs I brought in – Gadigal Land and First Nation – they were written with an undisguised anger. It may be quite a lot to ask artists like Kaleena Briggs to come in and sing lines like ‘we don’t need your strychnine’ about the poisoning of the original Australians and the horrors of what happened right up until relatively recently in this country,” he says.

“It’s got to be called out because that is part of what the Makarrata is all about; it refers to a coming together after struggle but it also refers to truth telling. And now is the time to tell that truth.”

Rapper Tasman Keith wrote his original verse in under an hour after hearing the backbone of First Nation in the studio.

He said he was hoping to hear a classic Oils track and years of practising his craft as a writer and rapper prepared him for the challenge of getting it done quickly on the day.

“I think that comes from experience but unfortunately from a lot of trauma and heartache in the community and family that I’ve seen,” he says.

“I know how to channel that emotion when I need to, to be ready for that moment.”

Keith says the significance of working with the iconic band didn’t dawn on him until weeks after the session.

“In the session, it was cool. And it wasn’t until about two weeks later, at a really random time, like 12 o’clock at night, and I was laying in bed and randomly thought ‘What the f …? I have a song with Midnight Oil’,” he says.

The album closes with a reading of the Uluru Statement of the Heart by Pat Anderson, Stan Grant, Adam Goodes, Ursula Yovich and Troy Cassar-Daley, underpinned by atmospheric guitar swirls from Moginie and Rotsey.

Country music superstar Cassar-Daley reads the section: “Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future.”

He closes out the album singing Moginie’s composition Come On Down, an invitation to gather around a literal or metaphorical campfire and “Get off those little screens/And find out what it all means”.

MORE NEWS:

Surprise special guests on new Midnight Oil song

Amy Shark gears up for NRL Grand Final debut

Barnesy and MasterChef judge’s secret food project

Cassar-Daley shares Hirst’s dream that one day the Uluru Statement will not only be taught in schools but all Australians can recite it from the heart.

“I had to stop a few times, I was really choked and not able to speak because I’m reading these words, that I’ve read before, as a representative of my own people … I felt so proud,” he says.

“It started out as an indigenous story about what we need to do to make things better, to start conversations to move things forward.

“Now it’s become everyone’s story and now I’m thinking about who else is going to hear this. It’s not just the band I am recording with but the people who buy their records and will have their discussions having their feed around the kitchen table or with their kids on the way to school.

“The truth is so beautiful and now it’s going to be out there.”

The Makarrata Project by Midnight Oil and more is out on October 30.

The band will perform on the opening episode of the second season of The Sound at 6pm on November 1 on ABC.

Originally published as Midnight Oil: Adam Goodes, Stan Grant and indigenous leaders in Uluru Statement of the Heart mural for new Oils album