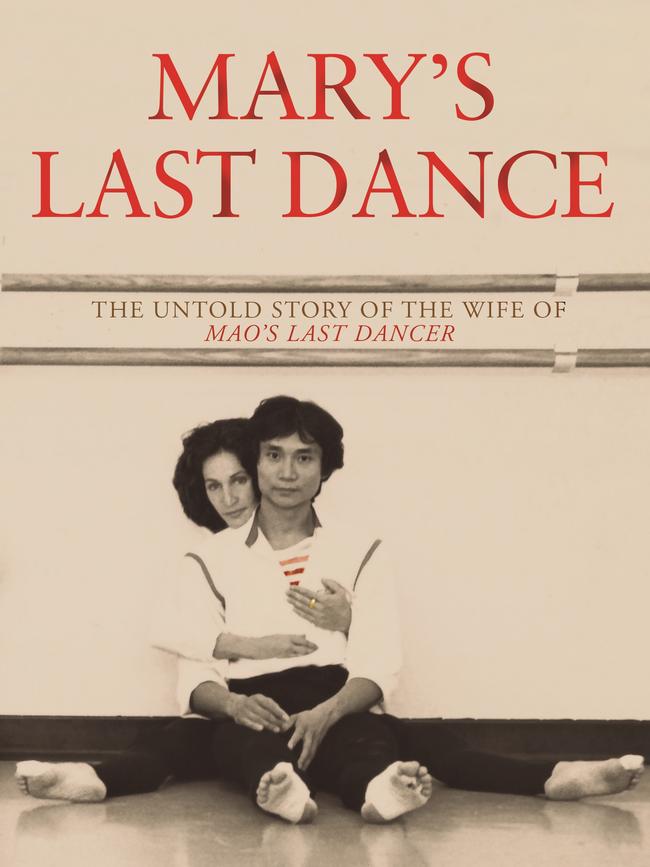

Mary’s Last Dance: incredible story of wife of fellow star and Mao’s Last Dancer author Li Cunxin

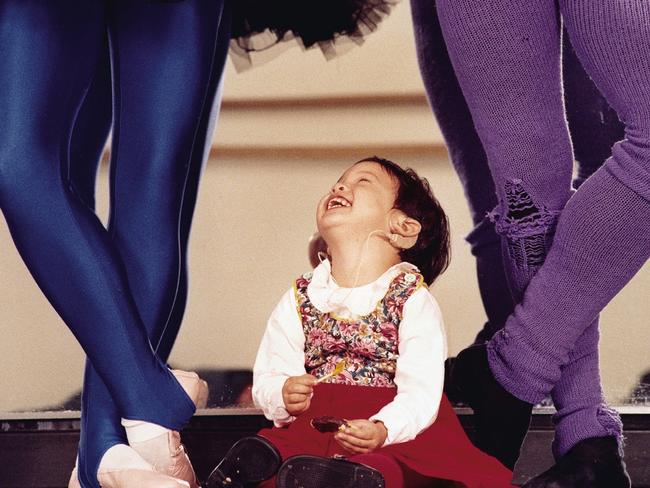

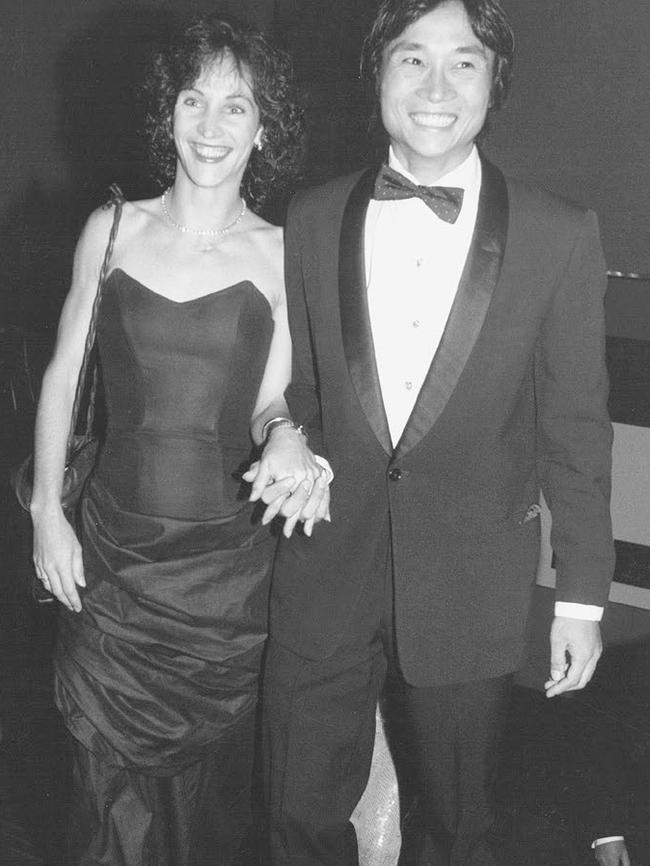

Australian international ballet sensation Mary Li — wife of fellow star and Mao’s Last Dancer author Li Cunxin — had the world at their feet until a shock diagnosis.

Books & Magazines

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books & Magazines. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Australian international ballet sensation Mary Li — wife of fellow star and Mao’s Last Dancer author Li Cunxin — this week releases her own highly-anticipated memoir, Mary’s Last Dance.

In this exclusive edited extract, she tells how an incident on a trip home to Australia set the couple on an unwanted journey of discovery and led to a stark choice: their stellar careers or their daughter’s health and happiness.

The next day, Li, Sophie and some of the others went to a park.

I was in the flat helping (Li’s mother) Niang prepare the food for dinner. A couple of hours later, Li and the others arrived back. Sophie was hanging onto a string with a burst red balloon at the end of it. Everyone bustled around and started to ooh and aah at the lovely smells emanating from the kitchen and the hundreds of dumplings Niang had made.

Li took me to one side, clearly agitated. I asked, ‘What? What’s the matter, Li?’

‘Mary,’ he said with a worried look on his face, ‘we passed birthday party on way back. Balloons everywhere and Sophie got hold of one. I was following her upstairs and balloon popped with loud bang.’

‘Yes, yes, I saw that. I hope she put it in the bin,’ I said, and turned back to the pastry.

But Li said, ‘I think something going on with Sophie. She right in front of me coming upstairs. When balloon popped, other children all startled but not Sophie. She didn’t move.’

‘So what?’

‘Mary, you’re not listening,’ he persisted. ‘The balloon popped. It was very loud and Sophie just stood there. All other children startled.’

‘What do you mean, Li?’ ‘She didn’t move.’

‘Don’t worry,’ I said. ‘She’s fine.’

I completely dismissed what Li was trying to say at that moment – Sophie was fine. She was meeting all the baby stages according to the books, and although she was a bit late talking, she was definitely making sounds, babbling and pointing, just like any other baby her age. She was such a perfect child, didn’t hide behind my skirt and just had a wonderfully calm personality. Nevertheless, I knew that Li – ever the doting father – was worried. So when he said, ‘Let’s go and see the doctor when we get back,’ I agreed. But I was still not overly worried.

***

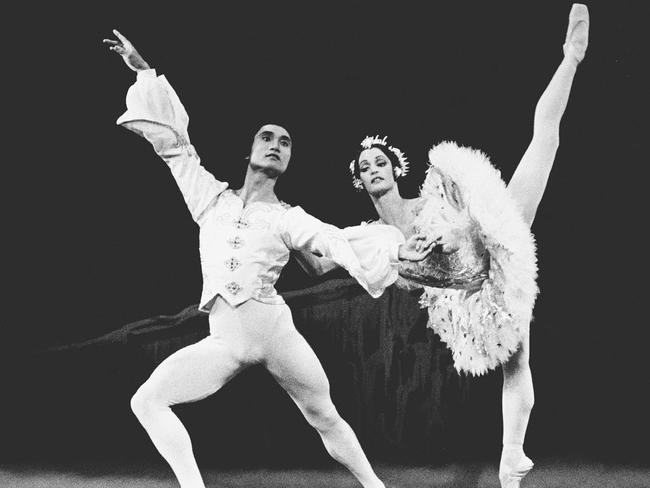

Our ten-day visit to Australia was over rather quickly. As soon as we landed in Houston, we were back to rehearsals for the Christmas season of The Nutcracker. I was to dance the role of the Sugar Plum Fairy with Li as my Prince. We were totally exhausted, as Sophie again was experiencing some dreadful jet lag and wouldn’t go to sleep.

My concern at Sophie not reacting to the balloon was getting stronger. I did watch her more closely, but I still refused to believe anything was really wrong. Nevertheless, I made an appointment to see our paediatrician on our first company-free day.

Our worries were only increased a few days later, when Annie was visiting with baby Nina. Li came in the front door and the screen door slammed loudly behind him. We all jumped – except Sophie. Little Nina was about to burst into tears, but Sophie didn’t even flinch. ‘She didn’t react to that noise. I’m going to do it again,’ Li said worriedly. Sophie was sitting with her back to the door as, once again, Li let it slam loudly. No reaction.

When we went to our appointment, the doctor didn’t seem worried. ‘Sophie is being brought up in a bilingual family, so her language acquisition is bound to be a bit slow. I think an auditory brainstem response test would be a waste of time and money.’

Again I felt reassured, but Li continued to insist on a proper hearing test – an ABR test. In the end, the doctor begrudgingly wrote the referral. We booked the first available appointment, which was six weeks later. In the meantime, we began testing her hearing. ‘Sophie! Sophie!’ we’d call. Sometimes she’d turn and sometimes she wouldn’t, so we still weren’t sure.

I was more positive than Li. ‘See, she turned this time. I think she’s fine,’ I’d say.

Before we knew it, Christmas was upon us. Then the six weeks had passed and it was time to take Sophie for her hearing test.

When we arrived at the hospital, the specialist explained that Sophie would be given an anaesthetic. She was to be put to sleep before the sensors were placed on her head for the ABR test. These sensors would send sounds over 100 decibels to her brain. Normal conversation is about 30 decibels so this was pretty loud – like a motorbike or a jackhammer. It was all quite alarming.

‘Won’t that wake her up, doctor?’ asked Li, looking more than usually worried by now.

‘No, no. She won’t hear anything,’ said the specialist, ‘but we’ll be able to record any reactions from her brain sending nerve signals to register the sounds emitted.’

It sounded awful – poor Sophie! – but I was confident the results would give us peace of mind.

The test took about an hour and the doctor returned to us at the end. We both stood up straight away, waiting to hear the good news. ‘How is she, doctor?’ asked Li anxiously.

Without any preamble, the specialist said, ‘Your daughter is profoundly deaf.’

Just like that, he delivered his verdict.

We were dumbfounded. We kept staring at this stranger in the white coat and then at our child, thinking this could not be true. Li tried to speak, but nothing came out. I was speechless too. We were in total shock. We felt our perfect world had fallen apart. A bomb had exploded in my head. I couldn’t comprehend what had just happened, or what it all meant.

Eventually Li said, ‘Can we fix this?’ His voice sounded so hopeful and yet so hollow.

How? I thought. I knew nothing could fix it. I had seen the movie about Helen Keller. I knew what this meant. In an instant, I could see some of the scary reality of what lay ahead. Then I was struck by all the things Sophie would never hear.

The doctor left the room after advising us to go to the nearest deaf school and have Sophie fitted for hearing aids. He was so matter-of-fact and unemotional. There were no brochures given, just a few little words and facts exchanged. He spent less than five minutes with us. We were completely blindsided.

Soon I would learn that appointments involving the hearing booth would always cause me great agony.

***

We had walked into that hospital with our little girl and a very special life, but Li and I knew everything had changed in that instant. That was it. There was no way for us to communicate with Sophie.

We drove home in silence, dumbfounded. My mind was a jumbled mess. Sophie was in her car seat but we both kept looking behind at her. I knew from her expression that she felt something was going on – she was quite intuitive in that sense.

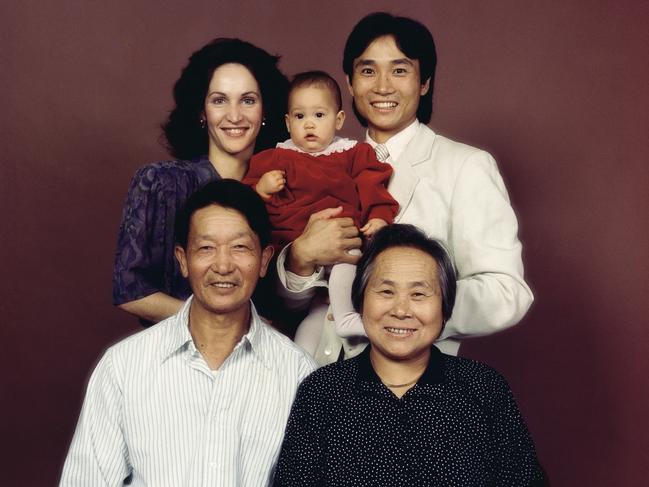

Li carried Sophie from the car, and then we laboured up to the front porch with the heaviest of hearts. I watched Li deliver the most devastating news to his parents in their Qingdao dialect. I could see their happy expressions turn to shock, then disbelief and incredible sadness. Sophie could sense the new sadness in our home and walked innocently from one to the next staring at our faces, completely lost. She knew something was wrong, but didn’t realise that she was the reason.

Sophie had never heard their voices, or anything, ever. She’d never heard us say ‘I love you’. Would we ever hear her say ‘Mum’ or ‘Dad’, ‘Yeye’ or ‘Nana’? The only way she had read the world was from our faces. Niang and Dia were distraught for us and for her.

Li’s parents heated up some leftovers for lunch, but nobody had any appetite except Sophie. Afterwards, I took her for her nap, feeling so hollow, so helpless. I tried hard to stop my tears in front of her, but as soon as her eyes closed, I went to my own bed and curled into a ball, unable to hold back. All I wanted to do at that moment was to have my own space. My own space to cry and try to cope with my extreme distress.

When Li returned from work that evening, I was still numb and didn’t know what to do next. ‘Mary, chi fan ba.’ Mary, let’s eat, Niang said, peeking her head into our bedroom. I took one look at her red eyes and knew then that she was suffering a great deal, too. She had cooked a delicious dinner, but I still had no appetite. For the first time in my life, I felt sorry for myself. ‘Mary, guo le! ’ Enough! Niang said sternly as she gently slapped her hand on my shoulder. ‘What’s the use of crying? Get up and get on with your life. Help your daughter.’ There were no tears in her eyes now.

I sat up, wiped my eyes and followed her to the dining table. Niang’s words shook me to the core and deep down I knew that she was right. I had to somehow shake off my self-pity and sorrow. Yes, this is my lot to deal with, I said to myself. Sophie is my daughter. I’m her mother. I have to help her. There’s no other way.

***

I knew we had to get Sophie fitted with hearing aids as soon as possible, as her diagnosis was very late. I had to stop my weeping if I was to ring the Houston School for Deaf Children. So I did. We were invited to come in for a meeting with Sophie on Monday. We met with the head of the school, an audiologist and two speech therapists, all sitting in a circle on the floor with Sophie on my lap. I could hardly take in what anyone was saying, and didn’t have a clue what the professionals were talking about when they spoke of what ‘profoundly deaf’ meant in terms of development and language. All I knew was that Sophie was eighteen months old and couldn’t hear.

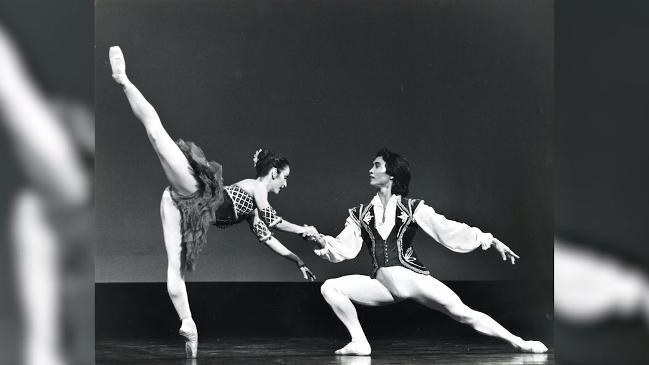

When it was our turn to speak, Li said, ‘My name is Li, this is Mary and Sophie. Mary and I are dancers at Houston Ballet. We’re just hoping you can tell us what’s the best thing for our daughter.’

‘Are you both planning on continuing to dance?’ the older speech therapist asked.

‘We would like to …’ I replied.

‘Do you want your child to speak?’ she asked calmly, looking at me. ‘Of course!’ I replied. And she looked at me quite doubtfully.

‘If you both want to continue your careers, then she probably won’t learn to speak,’ she said bluntly.

The full realisation hit me. Li’s eyes met mine and he understood, too. Diagnosis was one thing, but its implications were profound and everlasting. Sophie had not heard anything in her entire life. Her life had been completely visual. Suddenly I could feel the world moving forward but we were at a standstill. As devastating as the therapist’s words were, I knew she had spoken the truth and I admired her for this. Here, just when I needed her, was someone with knowledge and experience of this unfamiliar world.

The discussion moved on to language options for Sophie – sign, cued speech or oral method. For me signing was the last option. How could we keep working and both learn to sign? Even if I learned to sign, she would only be able to communicate with me and not with the rest of our family and friends. And she would never understand Chinese. I couldn’t see how signing would translate to the written words. How could she live without reading?

Cued speech was another option but was not very common. Like signing, it was a visual, phonic-based system, with small hand shapes near the lips representing consonants and vowels, and mouth movements supplementing these. But it was not verbal language.

‘I want to hear her voice,’ I said simply. This was my greatest desire.

Mary’s Last Dance by Mary Li is a sequel to Mao’s Last Dancer. Published by Viking, it will be available from November 3. RRP $34.99.

MORE NEWS

How Trump, Biden will change Australia and their allies

Sexy stars get political for US election

‘I’m ashamed to say I voted for Trump’

Originally published as Mary’s Last Dance: incredible story of wife of fellow star and Mao’s Last Dancer author Li Cunxin