Shelley Davidow on the Berlin Wall, an inappropriate relationship and a background of dark history

Australia’s Shelley Davidow was there when the Berlin Wall fell. Now she can reveal a story of impossible love set against the most heady – and horrific – moments of recent history.

Books & Magazines

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books & Magazines. Followed categories will be added to My News.

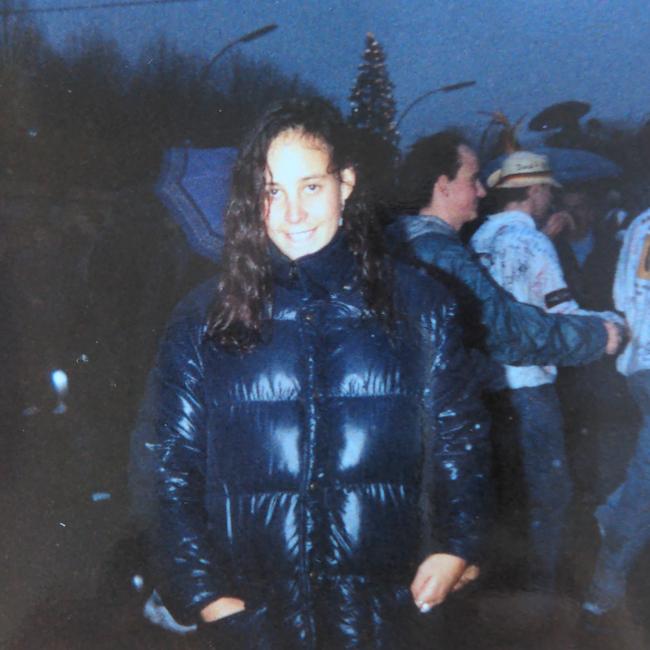

On November 9th, 1989, I was a young person at the Berlin Wall the night it came down.

In the soaking rain and cold, people my age were climbing up onto that wall – an activity impossible just days, hours, or maybe even minutes before.

A crane smashed through a section of concrete, revealing (for the first time since 1961), a view to the other side. It seemed that the entire population of East and West Berlin were trying to get through this gap at this moment, all at the same time.

I was caught in this physically dangerous and suffocating moment, breathing in the intense and heightened emotions of that night, and I understood I was bearing witness to, and part of, a significant historical event.

I’ve tried to recapture the feeling of that night at the wall in the opening scene of my novel when Susanna, my heroine, a 20-year-old Jewish-Australian violinist from Brisbane on a prestigious scholarship to Berlin, finds herself caught in this rushing moment, thrown against her beloved violin teacher, Stefan Heinemeyer, 17 years her senior, with whom she is falling in love.

The Girl with the Violin is fiction, but I have tapped into haunting emotional truths and my own ancestral legacy to write it.

Three years ago, while standing in the shower and inspired by the memory of that November night, the idea for the novel for The Girl with the Violin fell into my head. I saw it unfolding – a family saga/historical romance set in Australia and Berlin in 1989 – a woman’s journey to selfhood against layers of her own family story and some of the world’s darkest moments in history.

The novel explores the struggles of a gifted young violinist who dreams of becoming a luminous artist of worth in the face of big challenges. Once I was such a young woman: at twenty-two, I was living in South Africa when my first novel won an award and was published. But a week after the book came out, I left the country with almost nothing, wanting to escape violent civil unrest, unable to cope with living in so much fear.

I didn’t understand then, the repercussions of uprooting myself from the land of my birth. I couldn’t have foreseen the loss of self that often comes with the loss of a country – the vanishing of future dreams – what happens when you become a nobody in a new place, with no past to sink your roots into and no present to connect to. I’ve tried to capture some of that sense of not belonging as Susanna moves between continents and grapples with her own and her inherited traumas and dispositions.

Like Susanna, I’m the descendant of Jewish refugees. My great-grandfather Jacob ran from persecution and pogroms in Eastern Europe to America in 1913. His daughter (my grandmother Bertha), ended up in the Jewish Orphan Home in Ohio, USA. When she was 22 and had nothing and nowhere to go, she went out to Africa to marry my grandfather, whom she’d never met (he fell in love with a photo of her shown to him by her uncle) and asked her to marry him. My memoir Whisperings in the Blood (UQP, 2016) was my way of trying to honour the difficult life my grandmother lived; similarly, Susanna in The Girl with the Violin hopes to honour her grandmother Mirla, a Holocaust victim, by writing a musical composition in her memory.

The love relationships in the book are inspired by aspects of my own. As a young woman in a significant age-gap relationship, I was once at the mercy of harsh societal judgement which left me permanently changed. Like Susanna, I fell in love with German because of a boy. At 15, I was desperate to go to Germany to learn his language, be in it. Like my heroine, I did learn how to speak German fluently in less than 5 months. Loving the boy and loving the language were indistinguishable to me – perhaps that’s why it came to me so easily.

Importantly for a novel, though, I’m not anything like Susanna in many significant ways: for one, I am not a violinist. Susanna is my wish-fulfilment character. I did learn the violin for a couple of years, but my skills are rudimentary; when I hear a violin being played beautifully, I could cry forever.

Themes of intergenerational ‘whisperings’ of love, longing, geographical displacement, trauma and loss are part of the invisible layer beneath the story The Girl with the Violin – and are some of the elements I share with my fictional heroine. I hope that the book sheds light on how we are not our forefathers and foremothers. We may carry their stories and even their grief, but we have the possibility to change ours. I explore the idea that love is a kind of alchemical power that allows my characters (and us) to transcend inherited traumas and cultural divides.

So much to discuss here, from history’s earth-shattering events to love and leaving – so come to the Sunday Book Club group on Facebook and share your thoughts.

You can find Shelley Davidow’s The Girl with the Violin, published by HQ Fiction, at all good book shops.

More Coverage

Originally published as Shelley Davidow on the Berlin Wall, an inappropriate relationship and a background of dark history