Swimming Australia boss John Bertrand tells Pat Cummins how he removed the toxic culture and helped the Olympic team

In this extract from Tested, Australian cricket captain Pat Cummins discovers how America’s Cup champion John Bertrand turned the Aussie Olympic swimming team around.

Before the start of the 2012 London Olympics, Australian hopes and expectations were high, especially in the pool. Our country had a long tradition of excelling in the swimming competition, and the expectation was that Australia’s male sprinters would spearhead a successful team.

But it wasn’t to be. In race after race, many of the Australian swimmers performed below the viewing public’s expectations, and their own. After the final wall touch, the Australian swim team had managed to obtain just one gold medal from a total of ten for the whole Australian Olympic team. It was the worst result for an Australian Olympic swim team in twenty years.

John Bertrand was as involved in those Games as most of us were: as an interested spectator. John was the man who in 1983 as skipper of Australia 11, had won the America’s Cup for Australia for the first time, breaking a 132-year US domination with a vision, a mindset and a boat that weren’t just business as usual.

The Confederation of Australian Sport later went onto naming the Australia 11 victory as the greatest team performance in the last 200 years of Australian sport.

With those strengths, John told me he felt like his sailing team had a licence to break the mould: to think and train differently. To bring running and callisthenics – not something

commonly done by America’s Cup yachtsmen in the early eighties – into training, along with meditation, mindfulness and visualisation.

This kind of mental conditioning is now pretty standard in high-performance sports, as it’s scientifically proven to improve concentration and confidence, but back then it was about as derided as sunscreen and recycling. John wanted to instil in his team a calmness, a coolness and a belief that they could actually win the Cup, instead of being crushed under

the weight of expectation and history, and by the idea that failure was inevitable.

Since winning the America’s Cup, John had lived a life of achievement, but one that had often been out of the limelight. He stayed in competitive sailing, winning three world championships, the most recent in 2016, while also excelling in business. As an entrepreneur, he’d built companies in the marine industry and property development, and he had co-founded and launched a digital media company on the Nasdaq exchange in the United States.

Of the 2012 Olympics he said, ‘I’d just watched it and heard about the Stilnox stuff, that was all.’ The ‘Stilnox stuff’ was the persistent rumour, aired in the media, that some of the swimmers were abusing a drug used to aid sleep and that, perhaps while on the drug, some athletes may have bullied others.

John didn’t think too much about the 2012 Olympics when it was over, or the trials and tribulations of Australia’s swimmers – until he was contacted in 2013 by Clem Doherty, one the directors of Swimming Australia, to consider becoming the new president of Swimming Australia.

John told me that initially he didn’t have any interest in the position. He didn’t know much about swimming – in fact, he’d spent his life trying to stay above the water. Then he started thinking about the significance of the opportunity and what he could bring to it, in particular his experience in building high performance teams.

John loves sport and has seen first-hand what it can mean to a country. He loves sailing, but in 2013 he had no illusions about the international sportspeople who were most significant to the Australian public: the national cricket team and the national swimming team. John said he believed that helping either of those programs, if he could, was almost a patriotic obligation.

Believing he could help the national swimming program, he agreed to take on the role. ‘It was only when I got there that I realised how dysfunctional it all was,’ he told me.

John had heard that the organisation had become regrettably political, but he hadn’t known to what extent.

There were instances of extreme ego, fiefdoms, rivalries and embedded ways of doing things. All of these issues, he believed, were affecting the way the peak body operated, but they also filtered down to the national team, acting as an anchor and impacting performance. A report commissioned by the Swimming Australia board into the issues of the 2012 Olympic team suggested a similar conclusion, speaking of a toxic culture. The report indicated a ‘quietly growing lack of focus on people across the board’; this, according to the report, left the competing athletes ‘undefended, alone, alienated’. The report confirmed the media reporting of bullying and also the abuse of the drug Stilnox.

Shortly after arriving at the organisation, John wondered if it needed an almost complete reset. He believed that his attitude of over-the-horizon thinking would apply well in this situation, telling all involved that the plan would be to concentrate on radical, long-term future thinking. A business-as-usual attitude would not be accepted.

The move was cheered by the coaches, who felt they now were given licence to break free from the organisational shackles that they believed had been placed upon them and to put everyone else in the organisation on notice. This didn’t mean the people working at Swimming Australia were bad at their jobs, it just meant that things were to change quickly, and if anyone found it too hard to move with that change, then they might find it more comfortable to move on.

The Swimming Australia headquarters moved from Canberra to Melbourne, and of the fifty-five permanent staff who had been there when John arrived, only five were still there two years later. Now that the table had been cleared, a new way of doing things had to be established.

John decided that the new Swimming Australia culture might be informed by high-performing teams beyond the sporting arena. Two of the teams that he and the coaches were especially impressed with were the Australian Defence Force’s special forces – in particular the full-time commando force, the 2nd Commando Regiment – and the Queensland Ballet Company.

John and others from Swimming Australia made visits to Holsworthy Barracks, in south-west Sydney, home of the 2nd Commando Regiment and also the Special Forces Training Centre. John said he was amazed by how Australia’s Special Operations Command trained its soldiers to prepare for complex environments while dealing with stress at an existential level. He knew there were lessons that Swimming Australia could take from these soldiers, who had been trained to be in a state of total focus and team unity as they lined up in front of doors where, on the other side, there might be anything, including gunfire.

In the case of the Queensland Ballet, John noticed a different talent that he thought might be useful in a swimming context. He and the Swimming Australia coaches were taken through the dancers’ steps by artistic director Li Cunxin, formerly a principal dancer at the Australian Ballet and the subject of the book and film Mao’s Last Dancer.

With Cunxin’s interpretation, John saw ballet dancing in a way he never had before. He was amazed at how often the dancers made mistakes that were imperceptible to nearly anyone watching, and how injuries were accommodated and overcome on stage in real time.

The dancers’ environment and skills were completely different to those of the commandos: the dancers performed in a largely closed environment, and they were not focused on an end state but rather each step and movement, constantly adapting to be as close as possible to what was planned. John said, ‘They had an ability to totally get in their flow and stay in their flow. They make mistakes constantly, but no one ever notices because they are so attuned to their task, they can just adjust and keep going.’

A number of heuristics, methods and goals were developed for the high-performance swimmers, with one North Star sitting above all of this. ‘We call it “racing to calmness”. It’s moving into a world of slow motion. This was the dream. This is what we wanted for our athletes.’

John described exactly what that looks like for a hundred metre racer. The gun fires and they’re off the blocks in 0.5 seconds. Our swimmer takes six breaths in the first fifty metres, does a tumble turn, eight breaths in the next, with the last twenty metres just sprinting. They touch, look up, and see they’ve smashed both the world and Olympic records! They get out of the pool and say, ‘How easy was that,’ and add, ‘I can’t even remember the race.’ And it happened!

Performances started to change at the 2016 Rio Olympics, where the Australian team won three gold medals. But it was in Tokyo in 2021 that the most significant dividends were reaped. In the lead-up to the Tokyo Games, another huge cultural shift became embedded in the Olympic team, and that was a change of focus.

One of the most significant findings of the review ordered after the 2012 Games is that there had been an ‘increasingly desperate emphasis on gold’ – and in the rush to gold, the athletes had felt disconnected from the team and their teammates. This resulted in many of the swimmers telling the compilers of the report that they felt the London Games were, for them, ‘the lonely games’. A decision was made before the Tokyo Games to move the team focus away from gold medals and towards personal bests. In previous Olympics, Swimming Australia set a number of gold medals that would constitute a ‘good meet’ – that now went out the window.

The new key performance indicator was ‘conversion rate’: the percentage of Australian swimmers who had attained their own personal bests at the Games. The athletes were no longer told to strive for what the coaches believed would be a gold-medal-winning time; their entire performance focus within the team was now on attaining a personal best.

According to John, ‘We worked towards eliminating winning as a goal, because that wasn’t something necessarily you could control. You could control however your own personal best, so that’s what we wanted them to concentrate on.’

‘You already have to be one of the best eight swimmers in your discipline in the world to make our Olympic team, so we knew the performances would come.’

There was another cultural change that was explicitly sought for the 2020 Tokyo Games, one designed to foster team unity and also to improve comfort for athletes who were often still teenagers. Regardless of performance, gold-medals conversion rate or any other factor, there would be no judgement. ‘Trust was the key,’ John said. ‘Whether you win or lose, the arms go around you.’

In Tokyo, the Australian swim team won nine golds from a total of twenty-one medals. But better than that, they had a conversion rate of seventy-five per cent, more than twice the rate they had achieved at the 2016 Olympics.

This 2020 Olympic swim team became the most successful Australian swim team of all time.

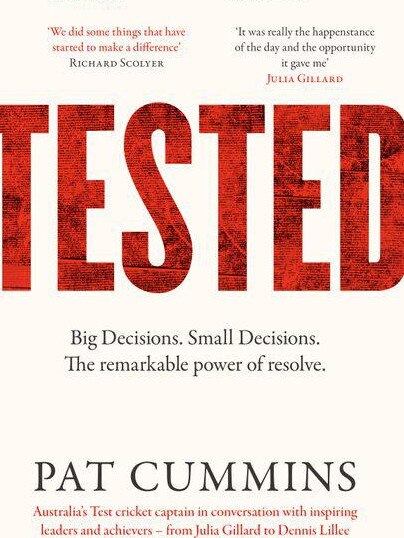

This is an edited extract from Tested by Pat Cummins: available now, published by HarperCollins.

More Coverage

Originally published as Swimming Australia boss John Bertrand tells Pat Cummins how he removed the toxic culture and helped the Olympic team