‘I’m going to get him’: Top cop Nick Kaldas on surviving the war against crime and terror

From going undercover as a hitman to facing Islamic terrorists overseas, one of Australia’s best-known law enforcers shares his secrets from the street.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

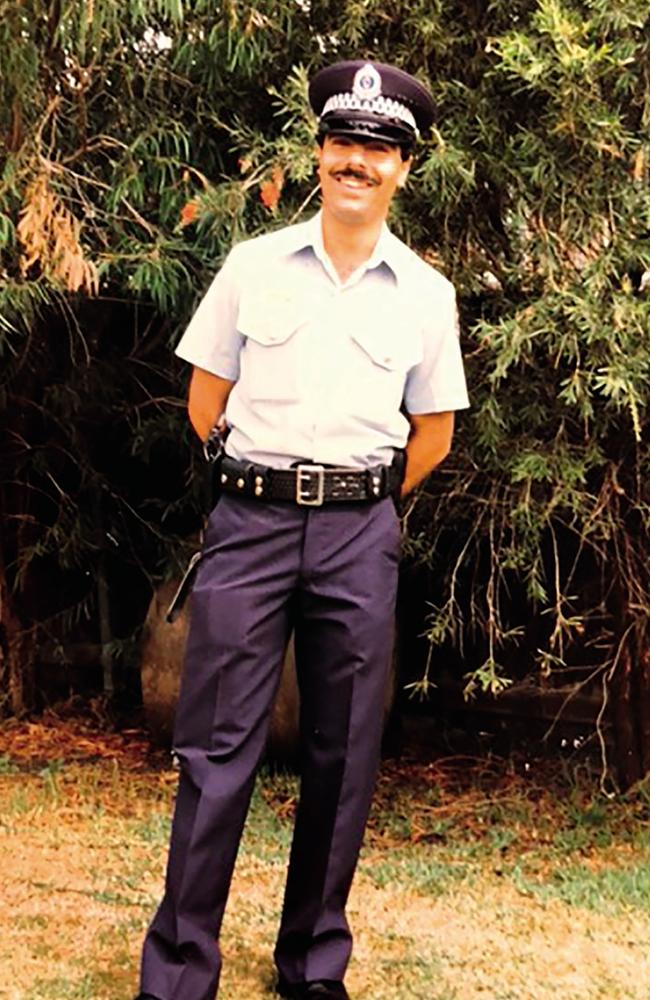

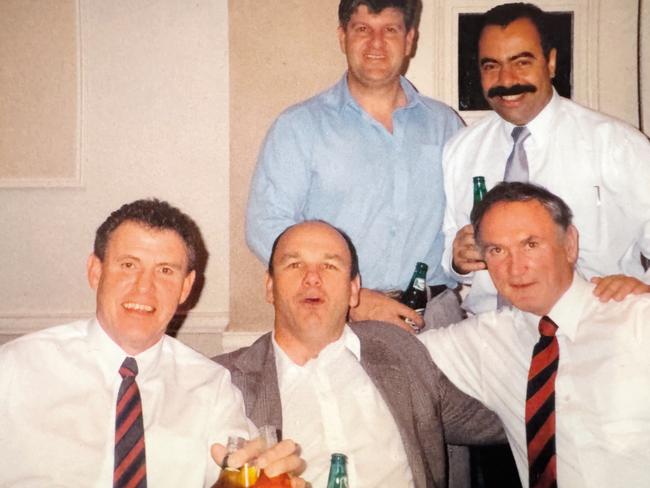

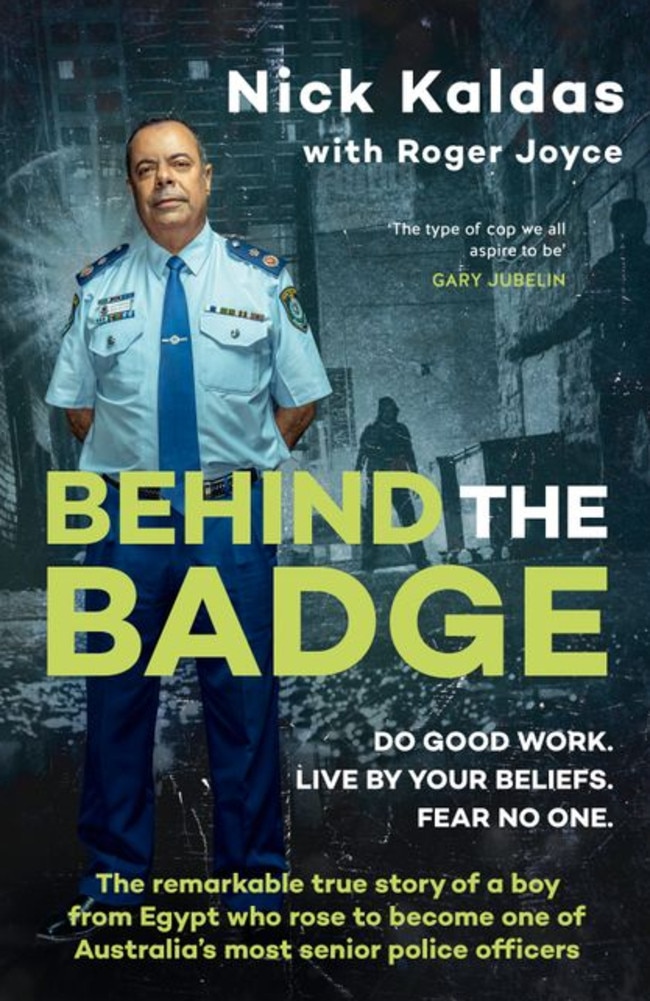

From fighting crime to confronting terrorists, former NSW Police Deputy Commissioner NICK KALDAS has seen a lot: as demonstrated in this edited extract from his memoir, Behind The Badge, which starts in his childhood with his family’s dramatic escape from authoritarian Egypt, via Beirut, for a new life in Australia.

On the day we arrived in Beirut, I walked in on my father with his suitcase open. He beckoned me over. ‘Come here,’ he said. ‘I know you’re worried. I couldn’t say anything before, but look …’

He opened the suitcase and carefully manoeuvred a false bottom. He pulled aside the original torn lining to reveal a coloured plastic sheet underneath.

I wasn’t prepared for what I saw when he removed the plastic. It covered a hidden layer of banknotes. There must have been tens of thousands of Egyptian pounds.

My father had quietly liquidated most of our assets and managed to smuggle the cash out of the country. He explained that the money in the case was our future.

He looked me straight in the eye, with his hands on my shoulders, and told me that we were going to be fine.

There were streetside stalls in Beirut where you could get money changed into different currencies. Bit by bit, so as not to attract attention, he would go out with some cash and change Egyptian pounds into American dollars.

Had the authorities at Cairo airport stopped my father and found the secret compartment in the case, I don’t know what would have happened to him.

After his family settled in Sydney, Nick went through school and eventually joined the NSW Police. He worked his way up, with periods spent undercover, in drug enforcement, homicide, gangs, armed robbery – and hostage negotiation.

HOSTAGE HOUSE

It was a dark night and we’d been called to a siege.

I was the primary negotiator.

A former South Vietnamese Army veteran, who was estranged from his wife and was clearly psychologically unstable, had taken his five-year-old son hostage in his wife’s home. He’d gone in, armed with an M1 carbine to confront his wife, but when he hadn’t found her, he’d shot and killed his mother-in-law and tied up his sister-in-law. She had managed to escape and raise the alarm.

By the time we arrived on the scene, there was a whole lot of media there. I had to ask myself: How do I negotiate with someone who’s already committed murder?

The street was cordoned off and the house was surrounded by the Tactical Operations Unit (TOU).

We waited for a long time, calling out to the man through a loudhailer, but he would not engage with us so I turned my attention to the boy. My son was about the same age, and thoughts of him kept running through my head.

Still speaking through the loudhailer, I was trying to get this little boy to stay at the front of the house, talking to us through the window. I had to keep him away from the door, so he wouldn’t get hurt if the TOU had to go in.

The siege continued for hours. The father was acting more and more erratically. Finally we came to the conclusion that he was going to harm the child, which meant that we had to act quickly.

The TOU crashed in with a lot of noise: the door was kicked down, flashbang grenades were released to disorient the hostage-taker, and there was a lot of yelling for people to get on the ground.

Then there was gunfire, as the father fired his M1 carbine at the first man through the door. Even though that officer had a bulletproof vest on, he was hit by a lot of ricocheting shrapnel.

The squad opened up on the father and subdued him. He was wounded but okay.

Understandably, while all this was happening, the little boy was having an absolute meltdown. I was frantically talking to him through the loudhailer, realising it was a matter of life or death for him if he walked into the firefight.

He remained at the window, but you could see he was utterly distressed and scared and wanted to go to his dad. I was yelling at him not to move, but I couldn’t go onto the premises to grab him.

I found it quite hard not being able to intervene.

Once the man was under arrest, it became clear just how volatile the situation had been. Not only had he been armed with the M1, but he also had bullets on the stove with a low flame going underneath them, and aerosol cans in different parts of the house with bullets strapped to them and fires underneath.

At the end of it all the negotiation team regrouped.

‘You look like shit, Nick,’ said our team leader. ‘You all right?’

‘Do I?’ I said. ‘Yeah, I’m okay.’

This was a lie.

REBELS, ROBBERS AND IDIOTS

Another case took place in a shopping centre out Greystanes way, west of Sydney’s CBD. We received information about a crooked employee who was passing on information to the Rebels Motorcycle Club. An informant warned a cash-in-transit company that one of their armoured vans collecting takings from the shops, and carrying very large amounts of cash, was going to be robbed. To this day we don’t know who the informant was.

On the day of the robbery, we had everything thoroughly planned out. As well as all of us, waiting in different places around the centre, we had police helicopters hovering nearby out of earshot, and the Special Weapons and Operations Section (SWOS) on standby.

On cue, the bad guys turned up. Then the targeted van arrived. We had to make a quick decision: would we grab the gang before they went into the shopping centre? The problem with doing that was that the chances of getting a conviction for a serious crime would be severely decreased, if not completely wiped out. They could say – even if they had weapons on them – that they weren’t planning on doing anything, which would mean we could only charge them with minor firearms offences. But if we let them go through with the robbery, we might have a gunfight on our hands.

Making a judgement call in the moment is tough.

The decision was made to let the gang go into the shopping centre. Two stayed outside while the other two went into a bottle shop, presumably intending to wait for the armoured van guys to come in to collect the takings, at which point the gang would ambush them and force them back to the van so the gang could empty it.

We waited for them to hold up the bottle shop, then eight of us, all armed, burst in. We took out the two guys who were inside the shop and the SWOS team grabbed the two crooks waiting outside.

The moment we crashed into the shop, one of the two idiots inside dropped his weapon and tried to play innocent.

He started walking from one aisle to another pretending to be a customer, telling me: ‘Thank God you’re here, Sergeant, there’s been an armed robbery.’

Rolling my eyes, I said, ‘Come here, old mate.’

All four pleaded guilty in the end and were convicted. Two were sworn members of the Rebels.

‘I’M GOING TO GET HIM’

‘I don’t give a shit whether you f**king kill him or what you f**kin’ do. You can maim him completely so it ruins his life. I don’t care.’

The wire I was wearing had captured everything said by Robert Ernest Neville, who thought he was hiring me as a hitman. He wanted me to kill a young male love-interest who had spurned his advances and taken out a restraining order against him, followed by defamation proceedings. Neville’s main motive for wanting to kill the younger man was financial: he feared losing a lot of money from the defamation case.

In 1998 I’d received a call from an old workmate from the Hold-Ups, who said to me: ‘We have a bloke up here in Coffs Harbour who is asking around for someone to kill a young bloke. Can you look at sending someone up to accept the contract – or can you do it for us?’

It sounded like an interesting job, so I decided to do it myself. I was confident I could pull it off. Having an ethnic background helped; looking at the background of the suspect, I thought it might be more credible if the assassin he was going to hire was not an Anglo-Saxon.

Dressed casually in jeans and a shirt, I knew I had to look and act like someone from the criminal milieu of Sydney who was capable of carrying out a murder. I already had a script in my head of how I would play things: there would be no joking or smiling but a fair bit of swearing.

I met Neville as arranged, and he gave me full details of the intended victim and $500 as a down payment, with the rest of the $5000 to be paid after I finished the job.

He suggested one way to get rid of the young man would be to run him off Eastern Dorrigo Way, inland from Coffs.

The young man travelled to and from work along this road on his motorbike, and parts of it were mountainous and extremely dangerous. Neville thought this would be cleaner than shooting, and it would look like an accident.

But in the end it would be up to me. ‘I don’t really care,’ he told me. ‘That isn’t my f**kin’ worry any more. I’m going to get him. If you don’t get him I’ll f**kin’ get him myself one night. I’ve got a small memory.’

We shook hands on the deal and I told him I would be in touch once the deed was done. Then I walked away with the $500 in my pocket and the whole conversation on tape.

Neville was arrested shortly afterwards.

FACING EVIL

Later, Nick’s career took him overseas: to war-torn Iraq, to help rebuild the police after the fall of Saddam Hussein, and later to lead a United Nations investigation into the assassination of former Lebanese prime minister Rafiq Hariri.

In Baghdad, along with Muqtada al-Sadr’s Shi’ite insurgency, we also faced the al-Qaeda insurgency, led by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a former Jordanian criminal radicalised in jail. Zarqawi’s methods went beyond even what al-Qaeda was comfortable with. Deadly, effective and ruthless, his hatred of Shi’ites was as strong as his hatred of the coalition forces.

On a May morning, one of our Iraqi colleagues, the Deputy Interior Minister Abdul-Jabbar Youssef al-Sheikhli, had a convoy waiting outside his house to pick him up. He came out but realised he had forgotten his keys, so he went back inside to get them.

Witnesses would later recall seeing a white Caprice car rolling down the hill just before he walked out again, then zigzagging outside his home and exploding.

The suicide bomb hit the convoy, killing five and injuring twenty. Charred wreckage was scattered everywhere. The deputy minister was injured but survived.

My colleague Doug Brand and I felt we had to go straight out there to show our solidarity and see if we could help. By the time we arrived with our protection team, the local community had gathered on the street. A couple of people began to scream at us, saying that this was all our fault, that we were not protecting them.

Doug and I spoke to them in an effort to de-escalate the situation. Our bodyguards tensed as we became hemmed in by the very large crowd.

One guy kept tugging at my sleeve. I brushed him off a couple of times, then finally turned around to see what he wanted. He was crying and holding a plastic shopping bag. It was full of human fingers and a hand.

I shall never forget the look of despair in his eyes. It brought home to me the evil we were up against.

The attack was later claimed to be the work of a group linked to al-Qaeda and Zarqawi. We drove back in silence. We knew that could have been any one of us. As I looked through the tinted window of the SUV, I wondered: How do we stop this? Are we ever going to win this thing?

Behind The Badge by Nick Kaldas will be published by HarperCollins on March 5.

Hear more from Nick on I Catch Killers with Gary Jubelin, wherever you get your podcasts.

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘I’m going to get him’: Top cop Nick Kaldas on surviving the war against crime and terror