Delicious food, exotic lovemaking … and danger: A story of island life and mainland death

A real-life memory of an island community led by women sparks a story of love, murder and the true cost of ignoring threats, by one of Australia’s best-known writers.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There is a pot of tea, a basket of scones, and Natalie is wearing one of Aunt Bertha’s 1917 petticoats as a dress – gloriously embroidered silk from one hundred years ago.

We sit in the garden while Natalie tells us the story of her grandmother, who “walked the beaches” of her remote island, till finally she found an injured sailor washed up in the rocks – “a beachie” – and carried him home.

Sailors’ voyages back then lasted three years, or longer. One in four died per voyage. Prospective husbands were scarce. Women ruled that South Atlantic island, as they do on many islands where men go sailing.

So when a woman found a “beachie” she cosseted him with delicious food and exotic lovemaking – every household passed on the recipes for those. But your knitting secured him. Each household had its own patterns. Once a man wore a woman’s socks he was hers, even if he didn’t realise it. No other household would steal him.

Like Mair in my new novel The Sea Captain’s Wife, Natalie’s grandmother violated island custom and left with her beachie. Mair’s husband has a family business in Australia to return to, unlike common sailors delighted to stay in their new comfort and security.

Back in Australia, Mair is expected to join the tradition of sea captain’s wives, living in the family mansion along with her new husband’s grandmother, mother, and cousin, all waiting for their own sea captains to return, bringing gifts and joyous reunions. After three months the husbands leave again in their repaired ships. The women cry on their “widow’s walk”, watching the ships sail off, then go back to the rich lives they thoroughly enjoy, with no men to cosset or obey: concerts, theatre, embroidering exquisite underwear while one reads novels to the others.

I wrote the first version of The Sea Captain’s Wife 50 years ago, studying Golding’s Lord of the Flies in Year 11. The wrecked boys in that book become barbarians: humanity is instinctively violent.

I didn’t believe it. I wrote a trilogy in rebuttal. In Book 1 young people are survive a wreck cast on the Great Barrier Reef. In Book 2, they decide to create their own utopia. In Book 3 utopia has been reached – through constant supervision by hidden cameras. The heroine rebels; poisons the hero’s dinner, but as he eats he explains what he will announce tomorrow: the cameras were faked. The islanders already understood that kindness and co-operation bring happiness. He dies in her arms as she melodramatically sobs a confession. Well, I was only 14.

The Sea Captain’s Wife is not a story of a utopia – or rather, it is a utopia, because the inhabitants have learned that helping each other to live happily is the best way to survive. Their castaway ancestors created a paradise on the slopes of a soilless, rocky volcanic island, living on what they could gather from the sea or what drifted onto its shores.

By the time Mair searches for her beachie, sailor sons and husbands have brought fruits and seed from all over the world; gardens and even forests have been created, families share their leftovers and every woman has a good stone house and sheltered courtyard built for her by the community.

The island women are loving, compassionate and capable. They are also ruthless. If a ram is stroppy, it’s eaten. If a beachie hits a woman he vanishes over the cliff. The community also exists below a volcano, but just as humanity prefers not to look at the dangers ahead, the islanders refuse to notice that the volcano is becoming more active until Michael, the beachie newcomer, points out what they’ve ignored.

Back in Australia, Mair has found another kind of “volcano’” – one by one the heirs to their family ship-owning fortune are being killed. Someone, either family or friend, is a psychopath. Only Mair, the outsider, sees the danger.

Right now each of us lives in the shadow of a volcano. Floods, fires, heatwaves and storms unthinkable 50 years ago are changing our lives. If we keep ignoring the danger, we’ll perish, not just in bushfires but in wars for resources, where we fight instead of building solutions. If we forge bonds between nations based on trust and need, instead of military alliances, we will not only survive, but humanity’s lives in the late 21st century will be richer than ever before.

Solutions already exist for every major problem our world faces. We need the courage to accept tomorrow won’t always be like yesterday. We need to change our home designs, our ways of farming. We need our kids to learn that helping others creates community bonds, the kind needed when disaster strikes. Bussing the homeless out of sight, or installing curfews on kids will lead to even greater social divisions in the future.

Kindness and co-operation are what make us truly human, just as I believed when I was 14.

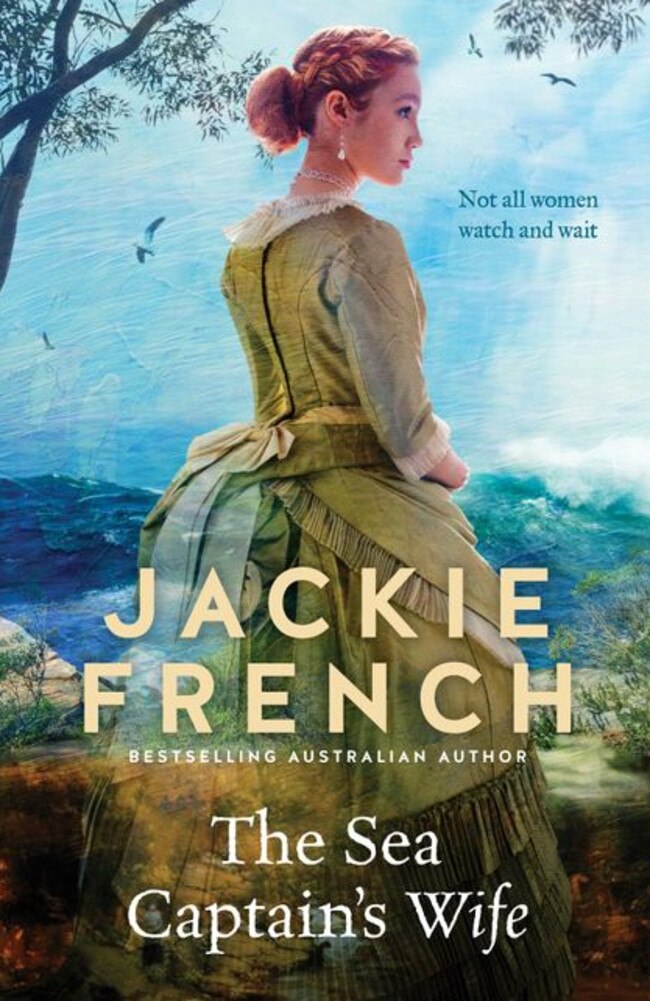

Jackie French AM is one of Australia’s best-known writers, penning stories for adults and children alike. Her new novel The Sea Captain’s Wife is available now, published by HQ Fiction. Let us know what you think, or what’s on your reading list, at the Sunday Book Club group on Facebook.

And check out our Book of the Month, Abigail Dean’s Day One. Get it for 30% off the RRP at Booktopia with the code DAYONE. T & Cs: Ends 30-Apr-2024. Only on ISBN 9780008389277. Not with any other offer.

Originally published as Delicious food, exotic lovemaking … and danger: A story of island life and mainland death