Victorian hotel inquiry: Six minute evidence gap remains a mystery

There is a mystery six-minute gap in Graham Ashton’s inquiry evidence which raises questions about who knew, and when, that private security would be used in quarantine hotels. If only officials could access the one piece of paperwork that could solve it.

HS Coronavirus News

Don't miss out on the headlines from HS Coronavirus News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Telephone records which could shed light on who in the Victorian government first decided to use private security in the hotel quarantine program are available – but cannot be presented to the inquiry.

The Sunday Herald Sun has confirmed the data Australia’s telecoms companies are required by law to keep includes the inbound phone calls their customers receive.

But privacy and other laws create hurdles which block the records being handed over.

The issue has been brought into sharp focus by evidence given to the hotel quarantine inquiry by former police chief commissioner Graham Ashton, who said he could not shed light on who might have given him information about private security because he could not obtain a record of his inbound phone calls.

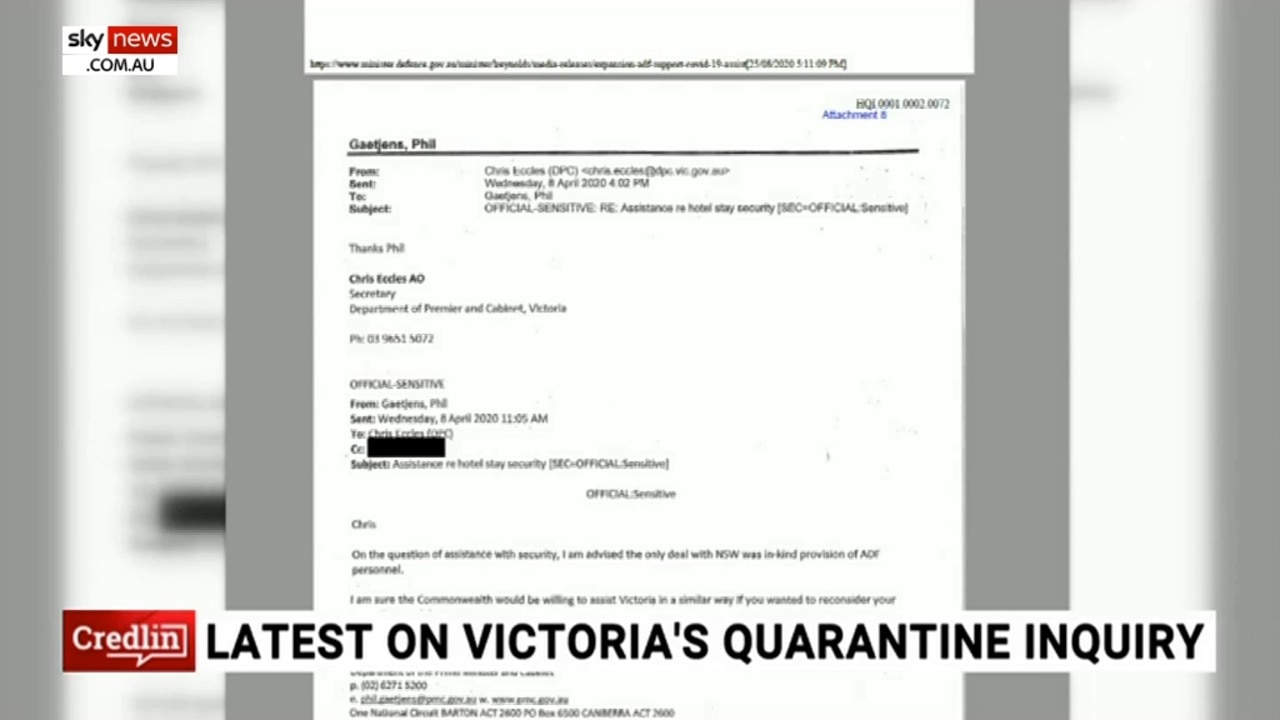

Department of Premier and Cabinet secretary Chris Eccles was also unable to provide inbound call records to the inquiry.

The lack of inbound call data is particularly crucial in the mystery six minutes where Mr Ashton apparently changes his belief on who will guard quarantine hotels, from police to private security guards.

There is a mystery six-minute window in his evidence which raises questions about who knew, and when, that private security would be used in quarantine hotels.

As National Cabinet was agreeing on a mandatory quarantine program on March 27, Mr Ashton sent text messages to Mr Kershaw, asking him about the use of police to guard the hotels.

He then appeared to change his view, texting Mr Kershaw that private security would be used, in a “deal set up’’ by Victoria’s Department of Premier and Cabinet.

He had texted the head of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, Mr Eccles, six minutes before he texted Mr Kershaw with his changed position.

But Mr Ashton told the inquiry he did not remember who he spoke to between those text messages, and said he only found out at 2pm that day from Emergency Services Commissioner Andrew Crisp that private security would be used. His records do not show whether Mr Eccles, or anyone else, rang him in the six minutes between the two texts were sent, because inbound calls were not included.

Mr Eccles has told the inquiry he has no records showing he called Mr Ashton, and believed it could not have been him as he didn’t know about hotel quarantine program at that early stage.

Mr Eccles gave evidence he had examined his own phone records and they did not show that he had returned Mr Ashton’s text or called him back.

He described himself as a “courteous individual’’ and said he would, in the normal course of events, respond to a contact from the chief commissioner.

“My phone records don’t reveal the contact. I’m not sure how complete my phone records are. But to the extent that I was able to interrogate my phone records, they didn’t reveal that contact,’’ he said.

Mr Eccles said it would not be routine, but it was “possible’’ he would get someone to respond to Mr Ashton if the chief commissioner had contacted him.

But he said he had not checked with his inner circle of staff to see if anyone had responded to Mr Ashton on his behalf on that day.

Experts say there are restrictions contained within both the Telecommunications (Interceptions and Access) Act 1979 and a court ruling in January 2017 which essentially made inbound calls unavailable to customers.

Geoff Holland, a barrister and lecturer in communications law at UTS in Sydney said Mr Ashton was correct in his assertion he could not gain access to his incoming call records.

“They’re only available to limited bodies and for limited reasons,’’ he said.

He said law enforcement agencies could only get access to inbound calls for the purposes of investigating criminal offences, or for investigating financial penalties for people who had deprived the commonwealth of income, such as through Centrelink or tax fraud.

And inbound calls had been found in a privacy test case in January 2017 to be the property of the person who made the call, not received it, meaning it was not handed over to customers who sought it.

There were other potential circumstances where the data could be obtained from telcos, such as during an investigation for a missing person, but these were extremely limited.

Mr Holland said it was possible the telcos had discretion and could provide the data to someone who asked for their inbound call record, but it would be highly unusual.

In the circumstances of a judicial inquiry, he said the Act did allow for the commonwealth Attorney-General to authorise a royal commission to access the data from the telcos, although only for the purposes of investigating a criminal offence.

“An application would need to be made to the Attorney-General for them to be included as an authorised agency,’’ he said.

However, the hotel quarantine inquiry is not investigating allegations of criminal behaviour so it is not known if the hotel quarantine inquiry, chaired by retired judge Jennifer Coate under the auspices of Victoria’s Inquiries Act 2014, would have any power to make such an application.

The inquiry declined to comment to the Sunday Herald Sun.

Mr Ashton, who retired in June, also declined to comment.

Victoria Police, as the account holder of the phone Mr Ashton was using in March this year when the hotel quarantine program was established, said it had tried to obtain the records.

“Victoria Police has gone to great lengths to co-operate fully with the inquiry as we understand the critical importance of its work,’’ a spokesman said.

“Victoria Police did contact Telstra and request incoming call data for the former chief commissioner’s phone but they advised correctly that under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 they are unable to provide that data unless it relates to a criminal investigation or missing-person investigation.’’

Mr Ashton provided two sets of records to the inquiry.

The first, a collection of WhatsApp messages between him and other senior figures including AFP Commissioner Reece Kershaw and Mr Eccles, were provided in a report compiled by the Israeli digital investigations company, Cellebrite.

The company is routinely used by law enforcement in Australia to access data contained within suspects’ phones, and is the FBI’s go-to company to hack into locked phones and obtain data on terrorism and serious crime matters.

Mr Ashton then prepared a second report at the request of the inquiry, for which he accessed billing records provided by Telstra to Victoria Police.

“Those records include details of my outgoing calls on 27 March 2020. They include also the calls which I received, but only those made to me by other Victoria Police executives,’’ he said in the second statement, dated September 16.

“Neither I nor Victoria Police now has access to records or any other incoming calls that I received at that date.’’

Clive Harfield, an associate professor at the University of the Sunshine Coast’s Institute for Cyber Investigations and Forensics, said telcos were only required to keep data on the “mechanics’’ of their customers’ communications.

“Any one communication may pass through several service providers and each provider must retain records in relation to that part of the service it provides,’’ he said.

“To that extent, a recipient’s service provider would keep a record of incoming calls.”

Prof Harfield said he was uncertain if the hotel quarantine inquiry could seek to access the inbound calls by applying to become an authorised agency. “Such an authority or body would not seem to satisfy the criteria,” he said.

MORE NEWS

Quarantine hotel guards axed, police step in

Why hotel quarantine inquiry must be reopened