How Australia will get more Covid jabs to rural and remote areas

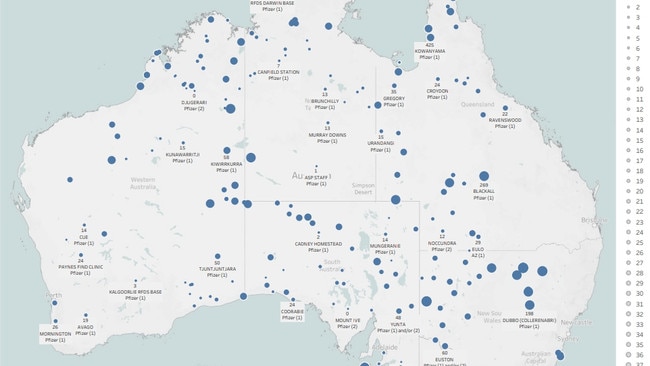

A new map has revealed another Covid battle Australia is fighting outside our cities to stop the spread. SEE WHERE YOU CAN GET THE JAB

Coronavirus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Coronavirus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Donnella Mills fears Covid-19 represents a loaded gun to her fellow Indigenous Australian.

As National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation Chair (NACCHO), vaccination is a key priority. There 143 Aboriginal community controlled health organisations with more than 500 clinics currently trying to get jabs in arms with the help of the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

Given what has happened to the Navajo and Amazonian Indigenous people, where Covid has cut a devastating swathe, NACCHO knew it could do the same in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population and worked to close off many vulnerable communities that have remained Covid free.

“We were able to use the powers in the biosecurity act to shut our remote communities,” Ms Mills said.

But Covid will eventually come.

“When I think of the devastation in other first nations, particularly the Navajo, that footprint, that traditional passage of law, language, culture and custom, it just stops,” Ms Mills said.

“So it is why we must, if we have questions, go to your doctor. We have to protect our longevity in the country, 60,000 years and we must keep going strong.”

And getting vaccination rates up in far flung communities is vital.

Some of the lowest rates are in WA northern region with only 10.86 fully vaccinated and 21.29 per cent fully vaccinated. Rates across all Indigenous communities are lower than all other groups across the board.

One key hurdles in the Indigenous vaccine rollout was the change in advice from the Australian Technical Advisory Group to recommend over 60s get AstraZeneca and Pfizer for those under 60.

“It has impacted all of us because the stock (of Pfizer) wasn’t available and so not only did we have to shift to Pfizer, Pfizer requires different ways of control, it requires refrigeration, so it wasn’t just the vaccine that we needed, we also needed the infrastructure around support holding the vaccine,” Ms Mills said.

But some communities are doing exceptionally well.

“Shout out to Northern Territory mob Maningreda they did over 65 per cent of their population over four days and in the Kimberly’s, they’ve had two pop up vaccination clinics and they have done in excess of 250 vaccinations each day. We have to get as close of possible to 100 per cent because of the fact we have 2.3 times the burden of disease than non-Indigenous Australians,” she said.

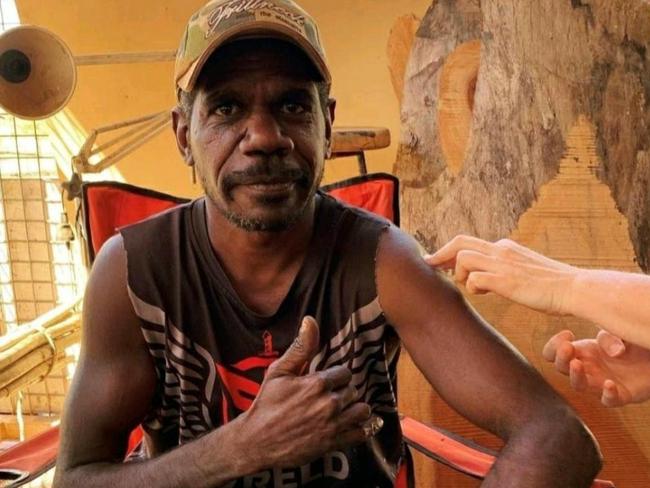

“Some of our services have been doing door to door if we identify if there may be an elder that can’t get to a clinic. We are reaching out and finding ways of bringing the vaccine to them.

“Our estimation of first dose to 80 per cent is the end of October, but what we are focused on, we want to be as close to if not 100 per cent and we hope to get there by the end of the year,” Ms Mills said.

Another hurdle has been vaccine hesitancy, and the anti-vaccine movement has targeted the Indigenous population with scare tactics.

“It has been so challenging, there has been such a direct intentional move to put this anti-vax narrative out there and what we’ve had to do is face that front on and make sure we keep communicating with all of our mob and identifying leaders in the community encourage them to keep coming to speak to us,” Ms Mills said.

“And we are making sure we get out elder leadership, our sport people, the trusted people to be able to make sure they are communicating with family.

Infectious diseases epidemiologist at the University of Queensland’s Poche Centre for Indigenous Health, Professor James Ward fears the worst is yet to come for his fellow Indigenous people.

“I feel like the cases are increasing and as cases increase, hospitalisation and ICU admissions will increase and ultimately deaths will increase.,” Prof Ward said.

“Vaccination is paramount to protect from further deaths.

“If we don’t get our population up to a significant level of vaccination coverage before Covid comes in to their communities and it is not if, it’s when. If we have pockets of populations at less than 80 per cent, we will be in dire consequence because those communities, if Covid comes in to those who are not vaccinated, it will spread like wildfire,” Prof Ward said.

Wilcannia in NSW, population 700, was exposed to Covid on August 13 and within a month more than 100 people had Covid.

“Wilcannia tells many things. It was a town already with a high burden of chronic disease and previously reported as one of the towns with the lowest life expectancy and really shows have inequities can play out in a pandemic,” Prof Ward said.

So far, there have been few deaths in the Indigenous population.

“The lives that have been lost have been predominantly unvaccinated. There have been three Covid related deaths among our community and the three were unvaccinated,” Ms Mills said.

“The most important message is if you have concerns, if you are worried, and so many of us are, but you have to go and yarn to your Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (ACCHO) or your doctor and put those questions to a trusted source,” Ms Mills said.

VACCINES IN RURAL AND REMOTE AREAS

National Rural Health Commissioner Professor Ruth Stewart consults with all rural and remote peak bodies to improve the health of those who live outside urban centres.

Prof Stewart chairs the network of the 80 General Practice Respiratory Clinics network which are the vaccination and hubs for rural and regional communities. They are as remote as Cobar, NSW, Kununurra in Western Australia, and Longreach in Queensland. Here she speaks with Jane Hansen.

Q How do the GP respiratory clinics (GPRC) work?

A There are 80 GPRC and they have been chosen to fill gaps in places where the state doesn’t have a vaccination centre. Both the state and the Commonwealth are pulling together to get people vaccinated.

The respiratory clinics were set up very rapidly, for example, I recently visited Emerald in central QLD and they put that together in three days using dongas. For a program rolled out very, very quickly, it has done surprisingly well.

Q Some communities like the East Pilbara, have only 22 per cent with one dose, 12 percent two doses, and the local government area of Grant in east South Australia where only 14 per cent have received one dose and 5.7 per cent two doses. Is it access or a supply issue in these areas?

A It’s an access and supply issue, but also an issue of will. I think some rural people think we don’t have Covid out here, particular remote communities think that but, all they need is one person with the Delta variant to moved through their community and it is gone. People will be infected very rapidly.

Q Is that is what happened in Wilcannia, NSW where one in six now has Covid?

A What has happened in Wilcannia illustrates very sadly the message I want to get out. People living in rural and regional Australia, if they are not vaccinated yet, they’ve got to make an appointment and get vaccinated. You can’t think ‘I live in the country and think I am safe from Covid’ nobody is safe from Covid unless fully vaccinated.

Q Are the vaccines actually available in rural and remote communities?

A They are and they aren’t. We’ve had lots and lots of AstraZeneca vaccine and it is an excellent vaccine that gives good immunity but people have been scared off it because of discussions about the TTS clot issue, but it is a very rare syndrome and we do actually know how to treat it. I encouraged my 25 year old son to go off and get it, but you just need to understand what the risks are, know what the signs are and line up for whatever vaccine you can get as soon as possible.

Q What have been some of the hurdles?

A In rural and remote areas we are always challenged by workforce and because Covid vaccine is new, there was a concern early on what the risks were so there was greater concern on having doctors present when people were being vaccinated. That is still the case, but we have developed more ways of vaccinating under the supervision of doctors, so there is that safety valve.

Q Western Australia seems to have the lowest vaccination rates in rural and remote areas, why is that?

A Remote communities were initially given AstraZeneca because you didn’t have to freeze it you could put it in an esky and drive or fly out for a couple of hours to a remote community and it could be stored in their fridge for a few weeks, all good. Then the announcement of Astra Zeneca being preferred for those over 6, that changed to who should get AstraZeneca and remote communities had to stop the planned rollout and begin to develop one of Pfizer.

Q What role has vaccine hesitancy played in vaccinating the indigenous population?

A If you are from a community where in your mother’s childhood children were removed from the community because ‘this is the best thing for you’ says the man from the government, you remember that more than any other message, so when 50 years down the track someone turns up and says there is this horrible disease killing people and we want to jab this in your arm, you need to have a careful conversation with that person.

It takes time and engagement and you will have a positive result with someone vaccine hesitant if they know you and trust you

Q What is at stake in rural and regional?

A Any community that doesn’t get over the 80 per cent of vaccination will be exposed to very high levels of infection and if there are an increased number in the community with co-morbidities, it is more likely people will die. If people have limited access to health care which we know they have across rural and remote Australia it is more likely they will get very sick.

More Coverage

Originally published as How Australia will get more Covid jabs to rural and remote areas