How 2020 is already the year from hell

A global pandemic, economic devastation, race riots and a presidential impeachment; In five short and terrible months, this year has seen a confluence of the worse crises of the past 100 years.

Coronavirus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Coronavirus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Shock video of cops walking over elderly man bleeding on floor

- Eight minutes 46 seconds: George Floyd’s final moments

In five short and terrible months, the United States has been faced with the ghosts of some of its biggest historical crises.

The coronavirus pandemic, in which the US has suffered more than a quarter of the recorded international death toll, echoed the Spanish flu of 1918.

It has sparked an economic collapse and unprecedented job losses, leading to talk of another Great Depression.

In January, although it now seems in the far distant past, the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump evoked the Nixon scandal.

As they did in 1968 after Martin Luther King’s assassination, Americans last week returned to manned space flight in the shadow of nationwide civil unrest sparked by the death of a black man.

There are even concerns from some that if this country can’t heal its current division, the next challenge could perhaps be a new iteration of its defining challenge: the Civil War of the 1860s.

“It’s like an anti-hit parade, a convergence of the greatest catastrophes of the past 100 years or so, all hitting us at once,” historian Thurston Clarke said this week.

And because news seems to break here on steroids, it’s all happened before we are even half way through 2020.

“All these things are being woven together,” said Mr Clarke, who chronicled Robert Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign and assassination in his book, The Last Campaign.

This was always going to be a big election year in the US.

Long before another heavy-handed white cop from the troubled Minneapolis police service used unwarranted lethal force in arresting a black man, America’s political, cultural and economic fault-lines were fracturing.

Under a mercurial president who inspires equal and passionate support and disdain, the US has become increasingly divided.

“The past decade has produced a parallel rise of populist and nationalist sentiment on the right and socialist sentiment on the left, leaving the political and social centre more barren than at any time in memory,” wrote Gerald Seib, executive editor of the Wall St Journal, in December.

“Mr Trump’s arrival heartened those on the populist right, who thought they finally had a president who understood their grievances, but infuriated those who thought he shattered social and political norms and used anger and divisiveness as political tools to his own benefit.

“By decade’s end, there was an unprecedented level of political division over Mr Trump, with fewer than 10 per cent of Democrats approving of his job performance and some 90 per cent of Republicans approving.”

That enmity emboldened Trump’s opponents to pursue with vigour their accusations that Mr Trump was at first a Russian asset, and later that he had pressured Ukraine to spy on his political rival. Almost all cable news at the turn of the decade was feverishly devoted to documenting these “crimes” after impeachment was initiated in December.

January was consumed with the impeachment trial, before the Senate in February acquitted Mr Trump of both counts, of obstruction of Congress and abuse of power.

It was at this point that the “China virus” began rapidly spreading through the world, after the belated, January 20 admission from Beijing that the SARS-like illness they had been dealing with for two months was contagious.

Within weeks, the economy had fallen off a cliff.

In March, when Mr Trump announced the first 15-days of social isolation shutdown to “flatten the curve”, predictions of 20 per cent jobs losses were labelled heresy, coming as they did just weeks after the US had recorded record job growth.

But as the lockdowns continued, tens of thousands of businesses closed and tens of millions of jobs evaporated.

When the May job report is released at 8.30am Friday in New York, unemployment is expected to hit 19.5 per cent, following April’s 14.5 per cent, the worst since the 1930s.

As the northern hemisphere has heated with the coming summer, so have tempers in the US.

Armed militia shut down Michigan’s legislature in protest to Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s continuing imposition of lockdowns. Texas bar owners used guns to head off officials who tried to close their doors. A Dallas hairdresser went to jail for opening her salon. New York Mayor Bill de Blasio has repeatedly dispatched police to stop Hasidic Jews from congregating in Brooklyn.

Fed up, and ever-conscious of what this economic devastation is doing to his re-election chances, Mr Trump has repeatedly urged states to reopen, even moving August’s Republican Convention out of North Carolina after the state’s governor said he would not lift coronavirus restrictions on assembly.

Unlike Australia, which has been so successful in crushing the COVID-19 spread, America has been brought to its knees.

For the past two months it’s been hard to find anyone in this country who wasn’t scared, frustrated, angry, grieving, broke or sick – or a combination of all of these states.

And then, at the end of a warm Memorial Day weekend, a clerk at the Cup Foods supermarket in South Minneapolis called police to report a suspected fake $20 note that a middle-aged man had used to buy cigarettes.

When four police officers arrived at the corner of East 38th St and Chicago Ave, they found 46-year-old George Floyd in the drivers seat of a blue SUV.

They asked the father-of-two if he was under the influence of any drugs or alcohol, before ordering him out of the Mercedes he was sitting in and trying to get him into one of their three squad cars.

Mr Floyd resisted and although he was handcuffed, Derek Chauvin – a veteran officer who had been the subject of at least 17 complaints since joining the Minneapolis police force in 2001 – used his knee to pin Mr Floyd to the ground.

He kept his knee on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds, three of them after Mr Floyd stopped breathing, despite him begging for air.

“I can’t breathe,” Mr Floyd said. “Please, don’t kill me.”

Seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier not only watched Mr Floyd’s death and asked the officers to stop, she also filmed it on her mobile phone and uploaded the clip social media.

And it was this video documentary of his savage death, crystal clear and suddenly viral, that changed everything.

“You can watch the slow motion destruction of this guy’s life,” says Professor Christopher Hayes from Rutger’s University.

“It has the all the trappings of an old time lynching.”

Protests that started that night in Minneapolis quickly spread to other cities and the coronavirus now seems a distant memory as the country is forced to once again grapple with the legacy of slavery.

Alicia Garza, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter, said: “There is literally a brewing civil war that is happening”.

Although the protests started peacefully and the majority of participants have been lawful, they have also drawn a series of bad actors.

Organised criminal gangs have joined looters in dozens in of cities while extremists with different causes have sown discord.

Prof Hayes described the resulting upheaval as the most significant since the civil rights era of the 1960s.

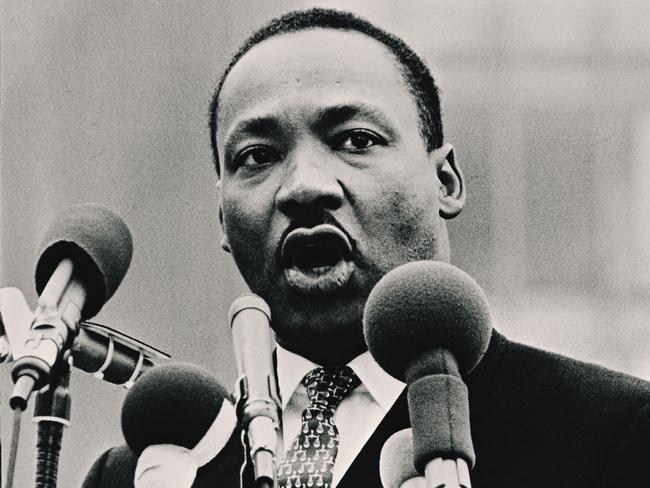

“In terms of the widespread nature of this, you would have to go back to 1968, when Dr (Martin Luther) King was assassinated,” he said last week.

“What that shows us is this Minneapolis situation is an American story.”

An urban historian who authored a book about the 1964 police killing of a black teenager and the protests that followed, Professor Hayes said Mr Floyd’s death was video was “the most vulgar and recent manifestation of how our society devalues black life”.

“The other ways are much less spectacular – residential segregation, poverty, limited opportunities, low-quality education and inequality in nearly every measurable index – and are always there, until a trauma too great to bear ignites it,” he said.

“This is an American problem that has endured across the centuries, and one that we continually refuse to meaningfully address.”

At a memorial yesterday for George Floyd, the first of three planned, celebrities joined political leaders and activists in Minneapolis, where they stood with the Floyd family for eight minutes and 46 seconds of silence.

“George Floyd’s story has been the story of black folks,” said the Reverend Al Sharpton, a civil rights activist and former presidential candidate.

“What happened to Floyd happens every day in this country — in education, in health services and in every area of American life. It’s time for us to stand up in George’s name and say, ’Get your knee off our necks’.”

Originally published as How 2020 is already the year from hell